_ Prof. Dr. Max Otte, German-American economist and fund manager. Munich, 10 May 2021.

Introduction

Germany, with an estimated 3.1 percent growth in 2021, comes out of the Corona crisis worse than the USA, China or the global economy as a whole and is falling behind with Europe. From previous crises Germany often recovered much better and better than many other EU countries. The growing together of Europe towards the lowest common denominator in terms of economic performance and export strength may be a currently practiced policy, but in the long term it can neither be productive for Germany nor for Europe.

This is an important symptom of the economic decline: the creeping recovery after a one-off or cyclical shock to the economy shows that the German export economy and the economy as a whole have massive structural weaknesses that might not be so noticeable in normal times.

The causes for the weakness of the German export economy are:

- Restrictions on free trade;

- Weak export and foreign trade promotion by the executive;

- Expanding the influence of states on the economy;

- in particular the “green transformation” (“Green Deal”);

- high burdens due to excessive bureaucracy;

- high and unsystematic tax burdens.

In addition to many correct and expedient policy recommendations, in the opinion of the expert there are also a number of misconceptions circulating among liberal politicians of the Bundestag since they are based on a partially outdated economic paradigm, namely that

- the world economic system functions according to similar rules in 2021 as in 1981;

- free trade and the associated unconditional export orientation of an economy should be assessed positively (almost) always and everywhere;

- state interference is (almost) always and everywhere disadvantageous.

Therefore, in this policy note, the changes in the global economy and the influence of states are first analysed and assessed. This is followed by a few short and concise statements on possible policy recommendations.

1. Situation analysis

1.1 De-globalization and transformation of the world economic system

According to the Bertelsmann Foundation, Corona essentially has two consequences: 1. the restriction of globalization and 2. accelerated digitization.[1] If the Rockefeller Foundation is included as a further source, then consequence 3. would be the expansion of the surveillance state and increasingly authoritarian forms of government also in the western industrial nations.[2]

For many, globalization was and is an irreversible dogma. But globalization actually runs in cycles. Already in 2006 I predicted a “bursting of the globalization bubble”: “Globalization itself has created a large bubble that sooner or later must either burst quickly or slowly deflate”.[3]

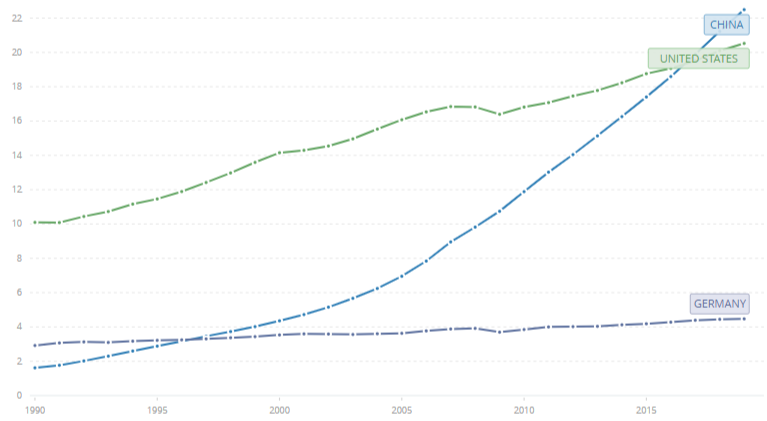

The reason is the relative rise of China and the relative decline of the USA. The “centre of the world economy is moving”. In terms of purchasing power parity, China overtook US economic output in 2017 (Chart 1).[4]

Chart 1. GDP (1990-2019, PPP, constant 2017 international USD)

Source: World Bank.

According to the “theory of hegemonic stability”, which is well-known in political science in the USA, an open world economic order requires a “hegemon” – a massively superior power that lays down the rules and ensures the open order.[5]

In the 19th century this power was Great Britain, after 1945 it was the USA. The hegemon certainly benefits most from such rules, but all other countries also benefit from the “global public good” of an open world order.

The USA reacts with an increasingly aggressive foreign trade policy, because the “liberal open world order” is also a US-centred hegemonic world order in which the USA understands how to exploit the advantages of its position. Washington is doing this more and more aggressively, also at the expense of Europe, by imposing painful sanctions on friendly or allied states. Examples include:

- The massive campaign against Nordstream II, which is in the interests of Germany and Europe in terms of diversifying energy sources and lowering energy prices (Germany has one of the highest energy prices among industrialized nations, which is a clear location disadvantage).

- The asymmetrical sanctions against Russia (the EU restricts trade, the USA primarily imposes sanctions on Russian people), which place a heavy burden on Germany and Austria in particular.

- The campaign against Germany’s automobile industry and diesel, which is mostly privately run, but also is certainly promoted by state policies in both countries – Germany and the USA.

China is now positioning itself with initiatives of a new “Silk Road” and an Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank in which Germany even participates against the will of the USA.

After Donald Trump was elected, the plans for the transatlantic free trade agreement were initially put on hold at the end of 2016. That is a good thing, because TTIP would have linked Germany and the EU to the USA and massively undermined the national competences of the European states.

After the financial crisis of 2009, a certain amount of renationalization took place in many financial markets. As one of the few financial markets, the German financial market is still open like a barn door for foreign financial products.

Brexit is also one of the series of deglobalization signals and tendencies.[6] The trade war that Donald Trump unleashed with China and the COVID-19 pandemic mark the final end of the wave of globalization that began after 1945.

Henrik Müller, chief economist at manager magazin and professor of business journalism at TU Dortmund University, has understood that there will be no “business as usual”.

“The world economic order dominated by the west is coming to an end – and things are likely to get worse,” he wrote in the summer of 2019. Müller sees three possible scenarios:[7]

- The new US president elected in 2020 could manage to unite the West again. A Western free trade area based on the model of the failed TTIP would arise. China, Russia and others would have to accept their rules – or stay outside. It is questionable whether Joe Biden can do that. In addition, a new TTIP would mean the extensive relinquishment of state competencies in foreign trade policy and the extensive economic “connection” of EU to the USA.

- Large trade blocs could be forming – the EU, USMECA (formerly NAFTA), and a China-dominated RCEP – which are open internally but relatively closed externally.

- Finally, a complete disintegration of the world economic order cannot be ruled out. The result would be a trade and currency war of all against all.

Henrik Müller sees scenario two as the most likely. German Crisis economist Daniel Stelter, on the other hand, is seeing increased signs of a currency war.

For world politics as a whole, I see three main scenarios, including military aspects: 1. a new “cold war” between an American-dominated and a Chinese-led bloc, 2. a hot global war, and 3. a reasonably stable greater area with more than two blocs.

Gabriel Felbermayr, President of the Institute for the World Economy, expects globalization to decline due to the virus. Companies are making their value chains more robust, and that is a good thing. What began in recent years is now being accelerated by the Corona crisis. The American administration under President Donald Trump is apparently working flat out to remove industrial supply chains from China.[8]

Even in open Germany they want to change the foreign trade regulation in order to make it more difficult for companies in the medical technology and pharmaceutical industries to take over in the future.

The situation in the global economy was precarious even before the corona pandemic. The corona pandemic is increasing tensions between the United States and China. In the USA there is a cross-party call to “punish” China. This is extremely dangerous because China is not a small country like Syria or Venezuela. The US insider and long-time dean of the Kennedy School of Government sees a real danger of war and already discussed this in 2018.[9] Even if it is possible to avoid an escalation, the world system will enter a new phase.

1.2 One-sided export bias of the German economy

The German Ministry of Economic Affairs summarized in September 2020: With a “degree of openness” (imports plus exports in relation to GDP) of around 87.8 percent, Germany continues to be the “most open” economy of the G7 countries. Due to its close integration into the global economy, employment in Germany is also highly dependent on open markets and international trade: around 28 percent of German jobs are directly or indirectly dependent on exports, and in manufacturing as much as 56 percent.[10]

The German economy has had a high structural external contribution (exports – imports) since the 1970s. In 2019, this external contribution was 5.8 percent of GDP, the trade surplus was 200.5 billion euros.

This high foreign trade surplus leads to high balances vis-à-vis “foreign countries”, which must be used to flow into foreign companies or real estate (real assets) or government bonds or into financial assets such as TARGET II balances. Few countries have as high a percentage of their exports as Germany.

Nevertheless, when it comes to household wealth, Germans bring up the rear in the eurozone. According to a recent study by the ECB in 2020, the average household in Italy has a net wealth of 132 thousand euros, that of Spain 119 thousand euros and that of France 118 thousand euros. The average German household, on the other hand, only has net wealth of 71 thousand euros, which is less than the euro zone average of 99 thousand euros.[11] And this despite the fact that Germans have a high savings rate compared to other countries.

This counterintuitive result can essentially be explained by two factors:

- The Germans invest their money poorly, namely predominantly in account and savings balances as well as in life and old age insurance. Equity and real estate holdings are low by international standards.

- Germany as a whole poorly invests its foreign assets, namely to a large extent also in monetary claims (e.g. the Target II balances) which generate little or no interest and are also affected by inflation. In the time since the financial crisis of 2009 alone, Germany could have built up between two and three trillion euros in additional foreign assets if we had invested our money as well as Canada or Norway. That would be between 28,000 and 37,500 euros per capita.[12]

The independent economist Daniel Stelter, formerly Senior Partner of the Boston Consulting Group, calls this phenomenon “saving without arriving”. The euro, which is too low for Germany, has three other negative structural effects in addition to the fact that the Germans are becoming poorer[13]:

- Other countries, or companies from other countries, are buying massive amounts of German companies and stocks. Even the USA, which is a large net foreign debtor, is using the low interest rates to buy German companies, to benefit from the earnings of German companies and to have a say. One example is the gigantic asset management company Blackrock with assets under management of over 1 trillion US dollars, which is the largest shareholder in almost all German companies. This means that both German medium-sized companies and the remaining large-scale industry are increasingly being dominated by foreign investors. With the high structural export surpluses, it should actually be the other way around: more and more shares in foreign companies should be in the hands of German investors. This paradoxical result is also the result of incorrect investment conditions for German capital in Germany.

- The pressure to adapt to German companies to increase their productivity and to pay reasonable wages and salaries is low. Instead, we have a massive increase in employment in the low-wage sector in Germany. This is a Pyrrhic victory. Switzerland shows that there is another way.

- The German economy is too export-heavy and is therefore particularly susceptible to crises, while the infrastructure in the country is falling into disrepair.

1.3 The German economy is oriented towards the past, poor investment conditions and ailing infrastructure

The strength of the German export economy and thus also of the German economy as a whole is often based on sectors in which Germany was already a leader during the boom at the time of the German Empire.

Michael Porter stated this as early as 1990 in his “National Competitive Advantages: Competing Successfully on the World Market”.[14] Germany is strong in the mid-tech sector (mechanical engineering, specialty chemicals, optics) but weak in high tech (information technology) and low tech (agriculture and raw materials).

In 2019, motor vehicles and their parts accounted for 16.8 percent of exports, machines 14.7 percent, chemical products 8.9 percent and IT equipment / electrical and optical products – 8.9 percent.

For a long time, Germany lost its leading positions, particularly in information technology, software and web-based services, and increasingly in the aerospace industry and in the civilian use of nuclear energy. With a few exceptions, Germany is falling behind in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries. As a result, German industry lacks the sectors of the future with high added value.

Labour and total factor productivity are declining in Germany and other industrial nations in the long term. Europe, Germany and the other Western industrialized nations absolutely have to achieve adequate productivity growth again in order to solve the demographic problem with old-age security, for example. Only if labour productivity increases can fewer workers care for more retirees.

The German national debt flowed mainly into unproductive government consumption such as pensions or spending on migration; necessary infrastructure investments for traffic, data networks, science, research, education and public safety were neglected. A study by the IW Cologne shows that the German state would have to invest at least 450 billion euros in the next ten years just to make up for shortfalls:

- 161 billion at the local level;

- 110 billion at national level for railways, broadband expansion and highways;

- 109 billion for education;

- climate mitigation efforts and social housing are not even included.[15]

Companies also made far too little investment in capital goods, research and innovation. Here, too, Germany is unfortunately a trendsetter, so that industry is emigrating: since 2016 alone, the share of industry has fallen from 23 to 21.5 percent today.

The low government investment strategy is wrong in several ways:

- insufficient investments worsen the local conditions,

- which reduces private investments,

- which in turn makes further private investments unattractive,

- which prevents the productivity gains that are badly needed.

The economist Daniel Stelter therefore proposes that macroeconomic investments in Germany should level at 25 percent of GDP and 3.5 percent of GDP for government investments. That would then be the level of France, but still well below the level of Japan. However, also an increase of 46 percent compared to the current level.

1.4 Counterproductive market organization, state intervention, laws and regulations

Complex regulations in the financial sector are a burden for SMEs and the middle class. The Volks- and Raiffeisenbanken as well as the savings banks have to meet costly and nonsensical requirements which large and speculatively oriented financial market players do not have to adhere to.

The automotive industry (diesel), retail (receipt requirement) and many other industries are being strangled by increasingly planned economic requirements.

The Green Deal, too, leads further in the direction of an eco-socialist planned economy, causes a further burden on most sectors of the German economy (energy prices, requirements) and is not suitable for building up industries of the future. The failure of the German solar industry, which has been hyped for a number of years, shows this clearly.

The trend towards ever more detailed and centralized regulations started on a large scale with the Delors Plan of 1988/89 (named after the then Commission President Jacques Delors), which wanted to reach the European Union through harmonization “from below”. What initially sounded quite interesting at the time has turned out to be the wrong path.

Another problem is the lack of proportionality in most regulations. Where comprehensive and strict rules are certainly necessary for nuclear power plants, large aircraft and complex financial products, the rules for medium-sized companies, self-employed individuals and regional banks ought to be significantly less comprehensive and strict.

The lobbies have often succeeded in turning the meaning of the rules around: for example, extremely detailed clarification and documentation obligations in banking mean that less and less advice can be given on share transactions for private customers and customers are driven into complex products.

Another example is the General Data Protection Regulation, which puts a massive burden on small and medium-sized companies, while data collection by the large, often non-European Internet companies, continues almost unchecked.

Since the same strict rules apply to all actors, all are subject to the same fixed costs of regulation. Fixed costs are easier to shoulder for larger companies, which makes regulation an instrument of active anti-SME policy.

Another very effective obstacle to productivity for the German economy is often hushed up: the practice of implementing the law in Germany is different (much stricter) than in a number of countries in southern Europe, France or even in many areas in the USA. This is also a significant cost factor and a competitive disadvantage, for example in areas such as the GDPR.

2. Conclusions

2.1.1 The world economic system has entered a new phase.

The big players – including the USA – are pursuing their own foreign trade policy interests more and more aggressively. Under these conditions, the scenario II by Prof. Henrik Müller – a certain re-regionalization – is the target scenario. It allows Europe and Germany to perceive their own foreign trade policy interests, to preserve European idiosyncrasies and to promote the growing together of Europe.

2.1.2 The one-sided export orientation of the German economy is not expedient.

It shows overconfidence when Germany, as a medium-sized industrial nation, makes it the basis of its own foreign trade policy to pursue free trade at any price. German politicians would do well to pursue a differentiated trade and foreign trade policy as a country or in association with EU partners within the German and European framework while free trade is fundamentally affirmed.

2.1.3 A better definition of German and European foreign trade policy interests is necessary.

It is important to recognize that all great powers have their own interests. This also applies to the US’s foreign trade policy, which can also have detrimental to very harmful effects on Germany and Europe. Foreign trade policy interests must be better defined at the German and European level.

An undifferentiated free trade doctrine is not expedient in the new global economic environment. The CETA in particular resulted in a further weakening of European and German competencies and a greater dependence on North America. However, US interests and German or European interests and approaches diverge more frequently.

A further undifferentiated opening of the German internal capital market for foreign financial actors is not expedient in the current global economic environment. Too much added value in German industry and in the service sector is dominated by foreign capital owners. This is actually a paradox as Germany is a capital surplus country. The list of sensitive sectors is therefore to be welcomed.

2.1.4 In addition to promoting exports, it also makes sense to increase investments in infrastructure and the future.

In view of Germany’s structural emphasis on exports, it makes sense to invest in future projects and to strengthen the domestic economy. That does not rule out intelligent saving in government spending in many areas. Private and public investments account for 21.8% of GDP in Germany, which is well above the USA (21.1%) and the UK (16.4%), but at the same time well behind France (23.3%) , Japan (24.6%) and Austria (25.7%). The front runners are Korea (31.4%) and resource-rich Norway (28.2%). With 3.8% of GDP, the Japanese state invests almost 60% more than Germany with 2.4%.

Germany is still one of the richest countries in the world. Through sensible state investments instead of senseless consumption as well as the promotion of private initiative and entrepreneurship, Germany must return to the path of productivity growth in order to regain its efficiency, the unique social partnership and the social consensus that have made our country so successful.

In this context, government infrastructure investments are also important, which increase the productivity of our country. This also includes better paid teachers and a better paid police force. These are ongoing expenses, but investing in education and public safety will ensure our future viability. That could be compared with research spending by pharmaceutical and IT groups, which are not direct investments in infrastructure either.

In “Das Märchen vom Reichen Land”, Daniel Stelter shows that we should not only increase our state investments, but can also save in many areas, i.e. from wealth-destroying (state) consumption, for example in the so-called euro rescue and migration be able to reallocate into meaningful expenses (Tab 1.).

Tab. 1. Germany consumes saves itself into ruin and instead of providing for future prosperity

|

Future prosperity

|

Should: intelligent restructuring | Should: investment |

| – Controlled immigration

– Reconstruction of the social system for migrants – Reconstruction of the welfare state financing – pension reform – Efficient state |

– Infrastructure (including digital)

– education, research and development – Eurozone restructuring |

|

| Is: wrong saving | Is: consumption | |

| – Insufficient investment in infrastructure and digital

– Bad education system – Police and public security – Bundeswehr not ready for action – Lack of industrial policy |

– Euro rescue

– Uncontrolled immigration – Welfare state – Pension policy – Energy transition – Subsidies |

|

| Current expense | ||

Source: Stelter D. (2018).

2.1.5 Reduction of bureaucracy and tax reforms

Although government investment is necessary, there is also potential for savings. Administrative expenditures for the welfare state have risen 40 percent faster than GDP since 1970.

We are employing more and more people to organize the redistribution. One of the reasons is that the laws and regulations have become so complex. The same is true for the health sector.

Accompanying measures would therefore be helpful:

- Reduction of bureaucracy and regulations according to the principle of proportionality.

- Implementation of regulations based on the principle of proportionality.

- Reform of the tax system and group taxation.

Large German companies in particular are often left alone politically at an international level. Therefore it is right to upgrade the foreign trade policy and to strengthen the possibilities of export financing and support for small and medium-sized enterprises or to reduce the foreign trade bureaucracy.

A moratorium on further information obligations for companies is to be welcomed, as is the review of burdens on companies (e.g. special cash registers) by a cabinet committee of the German federal government.

2.1.6. No privatization for the sake of privatization: increased efficiency must be the measure

A further undifferentiated drive for privatization ought to be rejected. The state has a role in providing public goods. Private companies are not per se more efficient than state-owned companies. In the old Federal Republic of Germany, Deutsche Bahn was headed by a department head from the Federal Ministry of Economics. There may be separate opinions about the service, but the train worked. Punctuality and reliability – important factors for a logistics company – were given.

Today, these two important factors can no longer be taken for granted. Instead, however, Deutsche Bahn AG now has a seven-person executive board, who received a fixed annual salary of more than 3 million euros in 2019.[16]

The US has a privatized health system that is also one of the most expensive and inefficient in industrialized nations.

Notes

[1] Habich J. (2021). Die Krise als Normalfall – Krisenmanagement in Zeiten von COVID-19. Bertelsmann Stiftung. URL: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/de/unsere-projekte/krisenmanagement-im-21-jahrhundert/projektnachrichten/corona-und-die-folgen

[2] Rockefeller Foundation (2010). Scenarios for the Future of Technology

and International Development. URL: https://norberthaering.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Scenarios-for-the-Future-ofTechnology-and-International-Development.pdf

[3] Otte M. (2006). Der Crash kommt. Die neue Weltwirtschaftskrise und wie Sie sich darauf vorbereiten. Econ.

[4] Otte M. (2019). Weltsystemcrash: Krisen, Unruhen und die Geburt einer neuen Weltordnung. FBV.

[5]Gilpin R. (1981). War and Change in World Politics. Cambridge University Press.

[6] Otte M. (2017). Der Brexit und andere Unfälle – tiefere Ursachen und Konsequenzen für die Deutsche Wirtschaft. List Forum für Wirtschafts- und Finanzpolitik.

[7] Müller H. (2019). Warum das Weltwirtschaftssystem weiter zerfallen wird. Spiegel. URL: https://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/handelskrieg-warum-das-weltwirtschaftssystem-weiter-zerfallen-wird-a-1277238.html

[8] FAZ. (2020). Trump-Regierung will Lieferketten aus China entfernen. URL: https://www.faz.net/aktuell/wirtschaft/corona-trump-regierung-will-lieferketten-aus-china-herausholen-16754747.html

[9] Allison G. (2018). Destined for War – Can America and China escape Thukydides’ Trap. Scribe UK.

[10] BMWi (2020). Fakten zum deutschen Außenhandel. URL: https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Aussenwirtschaft/fakten-zum-deuschen-aussenhandel.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=20

[11] ECB (2020). The Household Finance and Consumption Survey: Results from the 2017 wave. URL: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpsps/ecb.sps36~0245ed80c7.en.pdf?bd73411fbeb0a33928ce4c5ef2c5e872

[12] Stelter D. (2020). Coronomics. Nach dem Corona-Schock: Neustart aus der Krise. campus.

[13] Stelter D. (2018). Das Märchen vom reichen Land – wie die Politik uns ruiniert. FBV.

[14] Porter M.E. (1990). Nationale Wettbewerbsvorteile: Erfolgreich konkurrieren auf dem Weltmarkt. Ueberreuter.

[15] Hüther M., Kolev G. (2019). Investitionsfonds für Deutschland. IW Köln. URL: https://www.iwkoeln.de/studien/iw-policy-papers/beitrag/michael-huether-galina-kolev-investitionsfonds-fuer-deutschland.html

[16] Deutsche Bahn AG (2020). Integrierter Bericht 2019. URL: https://www.deutschebahn.com/resource/blob/5029910/5bdee6f2cac4fc869ad491d141539be9/Integrierter-Bericht-2019-data.pdf