_ Yuri Kofner, economist, Institute for Market Integration and Economic Policy. Munich, 21 July 2020.

Internalization of negative externalities

Environmental protection is an important social task that must be compatible with social justice and economic interests. The circular economy and the recycling of plastics are an essential part of this task. In 2019 Germany produced 6.3 million tons of plastic waste, which corresponds to 76 kg per person.[1] Worldwide, at least 8 million tons of plastic end up in our oceans every year and account for 80 percent of all marine litter.[2]

In order to reduce plastic waste, the German federal government introduced the Packaging Act in 2019, according to which at least 63 percent of plastics for packaging must be recycled by 2022. The mandatory quota currently is 36 percent.[3]

In addition, in 2021 the EU introduced the “National Plastic Contribution” (the so-called “EU plastic tax”), according to which the EU member states must pay 80 cents per tonne of plastic packaging waste that is not recycled on their territory. However, this measure was primarily introduced as a new source of income to finance the EU budget – it costs Germany 1.3 billion euros annually – and only has an indirect effect on reducing plastic waste, as reduction quotas are already binding in the EU.[4]

Also, in comparison to measures to reduce CO2 emissions, the negative external effects of plastic waste can be identified much more clearly and can therefore be priced more effectively.[5]

The green paradox also applies to recycling

Here too, as with CO2 pricing, the “Green Paradox” of the German economist Hans-Werner Sinn occurs.[6] National and European solo efforts to reduce the demand for newly produced plastics will only have the opposite effect:

First, a regionally limited reduction in demand for virgin plastics – polypropylene, polyethylene and PET, but also the intermediate product crude oil – will only make them cheaper on the world market (ceteris paribus). As a result, foreign manufacturing can and will consume more of it.

Second, plastic processing in Germany and Europe will be made more expensive indirectly through EU taxation of plastic waste (80 euro cents per ton from 2021) or a national recycling quota (63 percent from 2022), which ultimately will only lead to the emigration of the plastics processing industry abroad to cheaper production regions. Foreign produced virgin plastics (using crude oil) will thus also replace domestically recycled or virgin plastics. This phenomenon can be described as “plastic leakage” – just as the so-called “carbon leakage”.

Due to the relatively inexpensive virgin plastics made with new crude oil, the German deposit system (Pfandsystem) operates with a dangerously falling profit margin.[7] In Germany, a ton of recycled PET granulate costs just over 900 euros, whereas newly produced granulate made from oil only costs 680 euros. That is why in 2019 the share of recyclates in overall German plastic production was only 7 percent.[8]

In order to find a sustainable solution to the problem of plastics recycling, the solution approach should meet three basic principles: 1. It must be market-based; 2.be technology-neutral; and 3. designed globally.

Plastic bans, recycling quotas, mandatory increases in deposit rates (Pfandgeld), plastic taxes, etc., especially if they are limited to Germany and the EU, are therefore counterproductive. Recycling, and above all the actual use of plastic recyclates, must become economically interesting again.

The German company-based dual system (Grüner Punkt) is thus going in the right direction but is also reaching its limits.

Plastic certificates trade

A much more effective alternative could be the creation of a global trading system for plastic certificates, which would work according to the well-known “cap and trade” principle: The total amount of virgin plastic granulate that the sectors are allowed to use for processing is “capped” and gradually lowered. This total amount of virgin plastic allowances is divided into “plastic certificates”.

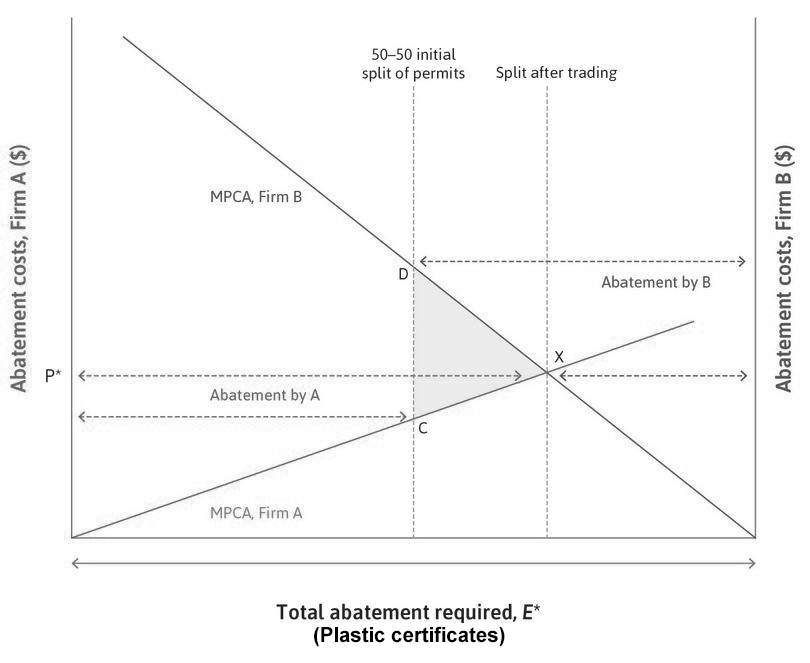

In order to be able to consume a certain amount of virgin plastic granulate, companies have to buy the corresponding amount of “plastic certificates” on the international plastic certificate market. Companies that produce more resource-efficiently and use less new plastic can sell their spare plastic certificates globally. Other virgin-plastic-intensive companies can then buy these allowances in turn. This means that the plastic certificates can be “traded” internationally (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. How the global trading system for plastic certificates works

Source: author’s graphic.

At the same time, companies that produce recycled plastics (recyclates) can themselves issue the appropriate quantities of plastic certificates (allowances), which they can then sell on the international plastic certificates market. This corresponds to the economic concept of integrating negative emissions technologies (NETs) into emissions trading systems.[9]

From a conceptual point of view, the integration of recyclate production reverses the process of a conventional cap-and-trade system. Every plastics processing company has to buy new plastic certificates for the amount of its virgin plastic consumption, since it is assumed that an increasing production of new plastic also increases the total amount of plastic waste (ceteris paribus).

If plastic waste is reduced through processing plastic waste into recyclates, new plastic allowances would re-enter the trading floor, as plastic recycling reduces the total amount of plastic waste. Just as carbon capture technologies could increase the supply elasticity of emissions allowances.

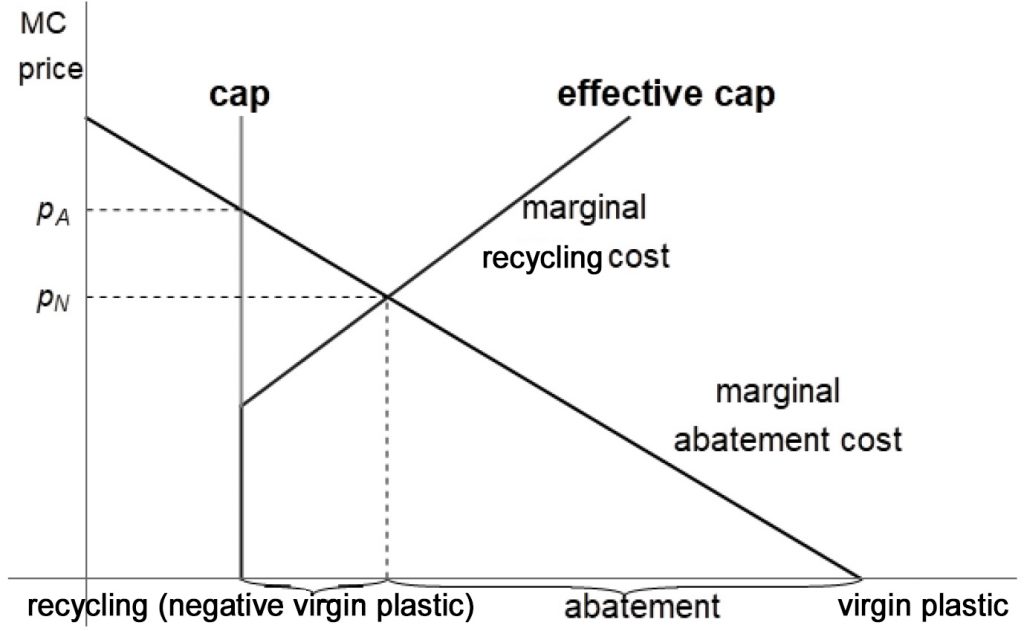

From an economic point of view, the provision of plastic certificates thanks to the production of recyclates would mean that the inelastic cap for the supply of plastic certificates would become elastic as the provision of plastic certificates would be profitable for recycling companies. Accordingly, we can differentiate between the overall cap set by a global regulatory authority and the effective cap resulting from the supply curve for plastic certificates (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Integration of the production of plastic recyclates (“negative” virgin plastics) into the trading system for plastic certificates

Source: Author’s graphic based on Rickels W. et al (2019).

The scarcity and tradability of allowances creates a certificate price, which in turn increases business incentives for plastics recycling.

The proceeds from the plastic certificate trading system should be used to fund research and development of plastic recycling technologies and the application of plastic alternatives. For comparison, in 2019 the EU emissions trading system generated 14 billion euros.[10]

The advantages of this system are that: it creates market-based incentives for the consumption of less virgin plastic and more recycles; increases sales for recycling companies; lets market forces identify the most efficient technologies and approaches to reducing plastic waste; and is global – which enables the production of oil-based virgin plastics to be reduced and the production recyclates to be increased there, where it is cheapest. Overall, the global amount of plastic waste is reduced most efficiently from an ecological, economic and technological point of view.

Policy recommendations

The EU should work at all levels for the creation of a global trading system for plastic certificates that would work according to the “cap and trade” principle and reward the processing of recycled plastic materials.

The German dual system (Grüner Punkt) can be integrated into such an international plastic allowances trade.

At the same time, the German federal government should abolish the plastic recycling quotas of the German Packaging Act of 2019. The EU should abolish its “National Plastic Contribution” of 2021.

The proceeds from the plastic certificate trading system should be used to fund research and development of plastic recycling technologies and the application of plastic alternatives.

Notes

[1] Istel K. (2021). Kunststoffabfälle in Deutschland. NABU. URL: https://www.nabu.de/umwelt-und-ressourcen/abfall-und-recycling/22033.html

[2] IUCN (2018). Marine plastics. URL: https://www.iucn.org/sites/dev/files/marine_plastics_issues_brief_final_0.pdf

[3] Neubig M. (2021). 30 Jahre Verpackungsgesetze in Deutschland. Deutschlandfunk. URL: https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/30-jahre-verpackungsgesetze-in-deutschland-muell-markt-moral.724.de.html?dram:article_id=499277

[4] Reichert G. (2021). The “EU Plastic Tax”. Greenwashing New Revenue for the EU Budget. cep. URL: https://www.cep.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/cep.eu/Studien/cepInput_EU_Plastic_Tax/cepInput_EU_Plastic_Tax.pdf

[5]Menner M., Reichert G. (2019). CO2-Steuer oder Emissionshandel? EU-Vorgaben und Optionen für eine CO2-Bepreisung in Deutschland. cep. URL: https://www.cep.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/cep.eu/Studien/cepAdhoc_CO2_Bepreisung/CO2-Steuer_oder_Emissionshandel.pdf

[6] Sinn H.W. (2020). Das grüne Gewitter. ifo Institut. URL: https://www.hanswernersinn.de/de/das-gruene-gewitter-faz-10012020

[7] Hannover J. (2021). Der schwierige Kampf gegen den Plastikmüll. Deutschlandfunk. URL: https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/das-problem-mit-dem-kunststoff-der-schwierige-kampf-gegen.724.de.html?dram:article_id=499695

[8] Klawitter N. (2020). Corona Plastic Boom. The Myth of German Recycling. Spiegel. URL: https://www.spiegel.de/international/business/corona-plastic-boom-the-myth-of-german-recycling-a-f136c2c7-09f2-40f3-8736-1b644f00da05

[9] Rickels W. et al. (2020). The Future of (Negative) Emissions Trading in the European Union. IfW Kiel. URL: https://www.ifw-kiel.de/experts/ifw/wilfried-rickels/the-future-of-negative-emissions-trading-in-the-european-union-15070/

[10] European Commission (2021). Auctioning of allowances. URL: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/ets/auctioning_en