_ Dr. Gunnar Beck, member of the European Parliament. Brussels, 15 July 2021.

Introduction

On Saturday 19 June 2021, the inaugural Plenary of the Conference of the Future of Europe took place in the European Parliament in Strasbourg.

The Conference Plenary will be composed of 108 representatives from the European Parliament, 54 from the Council (two per Member State) and 3 from the European Commission, as well as 108 representatives from all national Parliaments on an equal footing, and citizens. 108 citizens will participate to discuss ideas stemming from the Citizens’ Panels and the Multilingual Digital Platform, along with the President of the European Youth Forum.

During the inaugural Plenary, a total of 163 speakers took the floor: 40 Members of the European Parliament, 28 members of the Council of the EU, 27 citizens, representatives of national and regional parliaments, 6 representatives of civil society organisations, 5 members of the Commission, 9 members of the Committee of the Regions, 5 representatives of social partners, and 5 representatives of the European Economic and Social Committee.

This paper has two objectives: the first objective is analysing the speeches of the speakers of the Inaugural Plenary. Based on its content, each speech is categorized in one of three categories:

- pro-EU speeches, in which speakers advocate more integration, or a broader mandate of the Conference;

- EU-sceptic speeches, in which speakers voiced their or citizens’ discontent with the current level of integration, and where they have called for either more devolution of powers to the member states or for a more limited mandate of the Conference.

- Neutral speeches, where speakers did not voice ideological opinions, or limited their intervention to discussing technical and procedural issues.

Second, this paper addresses the regional and political balance among the speakers and evaluates their political affiliations.

There are four main conclusions: first, the Inaugural Plenary featured a clear majority of integrationist speakers, which is not in line with the latest available data from Eurobarometer on support for further institutional integration at EU level. Second, there is a clear disequilibrium in the geographic spread of speakers from the European Parliament and national and regional parliaments. While the European Parliament speakers only come from a limited number of Member States and are most likely to be from larger Member States, the speakers from national parliaments represent more Member States, and are more likely to represent smaller Member States. Third, the majority of speakers labelled as citizens, are engaged, and sometimes even gainfully employed in civil society organisations, blurring the difference between these two categories of speakers. Fourth: most civil society organisations represented at the Inaugural Plenary have a clear integrationist agenda, are intertwined with each other, and seem to lack true diversity of opinion.

Distribution of speakers

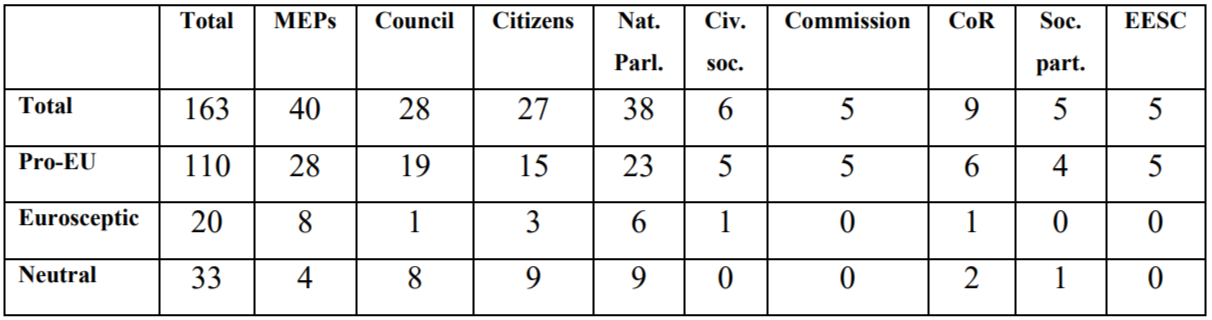

Table 1. Distribution of the speakers over the 9 categories and their speeches

Source: Compiled by the author.

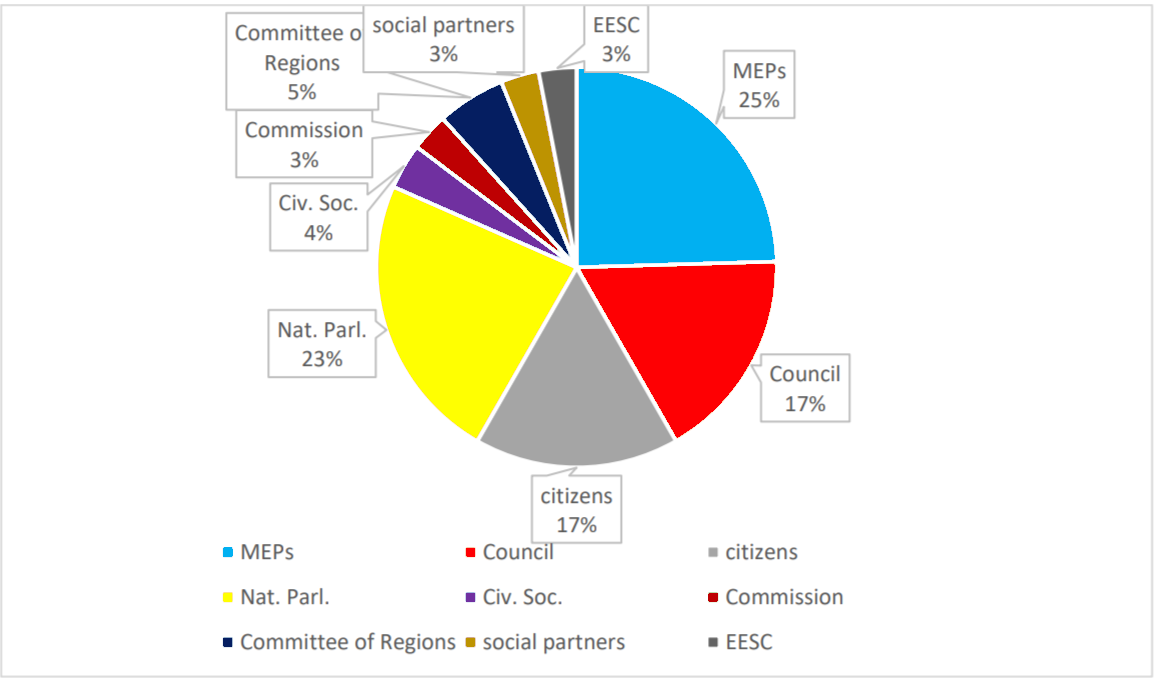

Fig. 1. Pie chart of the distribution of speakers over the 9 categories

Source: Compiled by the author.

Speakers at the Inaugural Plenary were distributed over 9 categories. As Table 1 and Figure 1 show, approximately half of the speakers consisted of Members of the European Parliament (25 percent) and Members of the national or regional parliaments (23 percent). Together with Members of the Council (17 percent) and citizens’ representatives (17 percent), these categories accounted for almost three quarters of all speakers. It is unclear why the distribution of speaking time between the categories of speakers is this skewed. If the purpose of the Conference is to give European citizens a say over the future direction of the European Union, it does not make sense to allocate the vast majority of speaking slots to speakers associated with the EU institutions in one way or another.

Views on European integration per category of speakers

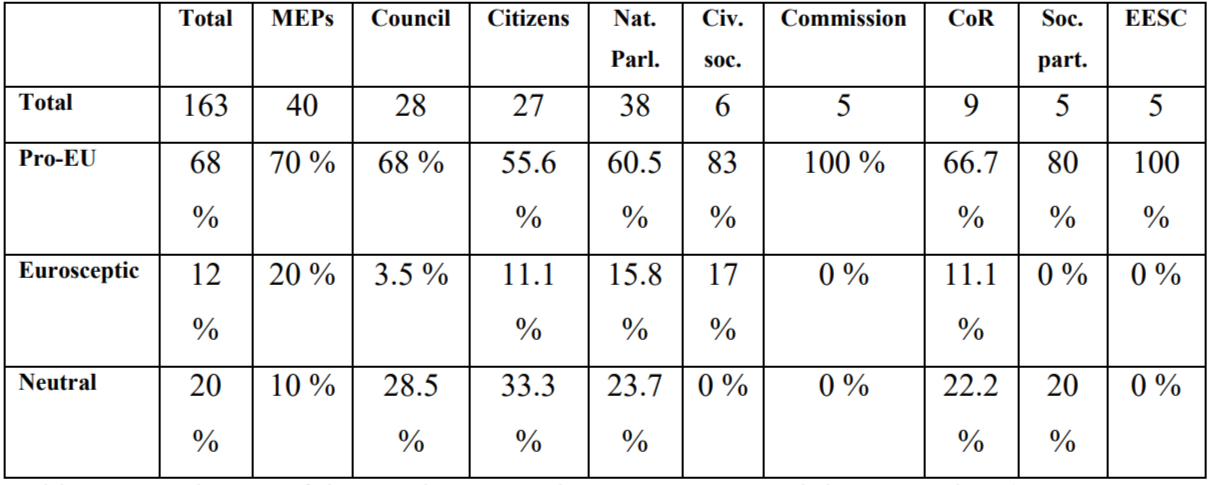

Table 2. Distribution of the speakers over the 9 categories and their speeches (in percentages, as share of total speakers per category

Source: Compiled by the author.

Tables 1 and 2 demonstrate a clear majority of integrationist speakers. 68 percent of speakers committed to fostering more European integration, closer cooperation and better cohesion between the member states, or enlargement of the EU. 20 percent of speakers expressed views of a technical nature, such as the importance of dialogues with citizens, outreach for hard to reach groups in society, or general wishes about the proceedings of the Conference. 12 percent of speakers expressed EU-sceptic views, calling for less European integration, more devolution of powers to Member States, or calling into question the democratic nature of the Conference. Compared to Special Eurobarometer 500 on the Future of Europe, only 42 percent of respondents would prefer more decisions to be taken at EU level than today, compared to 20 percent who would like to see fewer decisions being taken at EU level than today, and 34 percent of respondents agreeing with the current division of decision power between the EU and the Member States.[1] From these data, we can infer that the Inaugural Plenary of the Conference of the Future of Europe is biased towards more European integration than is actually desired by the European citizens.

When looking at the category of Members of the European Parliament, the share of pro-EU speeches is in line with the general trend (70 percent). However, more MEPs have spoken out against further European integration (20 percent). The percentage of EU-sceptic views expressed by MEPs in the Inaugural Plenary is consistent with the EU-sceptic views in the EU as measured by Eurobarometer.

Of the speakers in the Council group, only the Polish Minister of European Affairs, Mr. Konrad Krzysztof Szymanski, expressed EU-sceptic views. In his speech, he defended the principle of unanimity in the Council, which was heavily criticized by some speakers (mostly MEPs),[2] including Council speaker Luigi di Maio (Italy). He also called for greater respect of Christian conservative principles, and of political and national diversity.

The distribution of opinions among citizens’ representatives is less biased in favour of integrationist views compared to the other categories (55.6 percent), but still well above the Eurobarometer´s 42 percent. This seems to indicate that the citizens’ representatives are not a good sample of society, and still clearly biased in favour of more European integration. This highlights the need for further research into the recruitment and selection process of citizens´ representatives. Any selection bias might be theoretically explained by the hypothesis that people holding integrationist views are more likely to volunteer for becoming a citizens’ representative. To test this hypothesis, we would require further research, and any established bias needs to tackled by the Executive Board of the Conference on the Future of Europe.

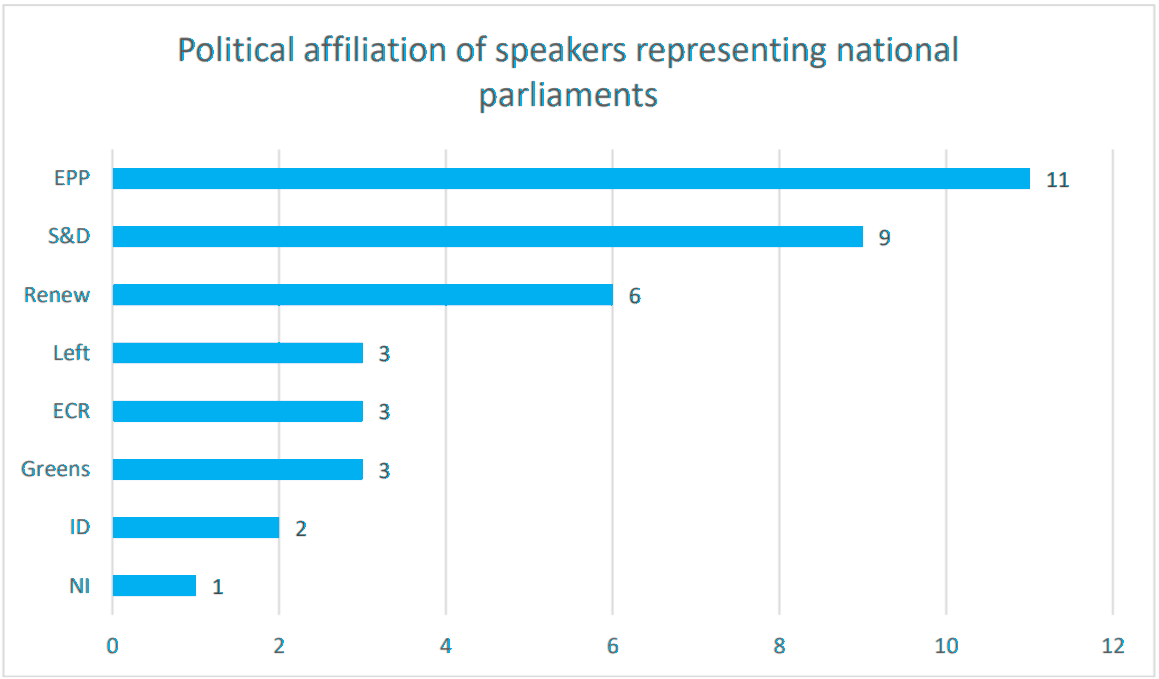

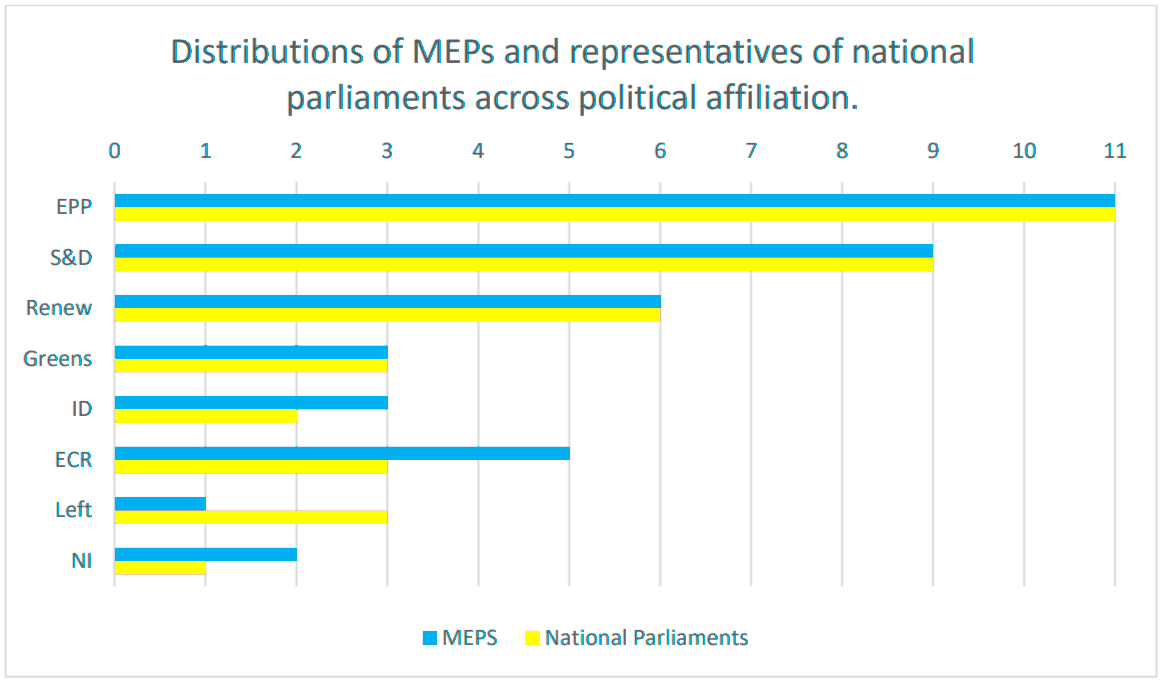

The pro-EU bias is also consistent in the group of speakers from national and regional parliaments (60.5 percent). This could be explained by two reasons: first, the political affiliation of this group of speakers broadly reflects the political strength of the various political groups in the European Parliament (see Fig. 3). However, the relative strength of the political groups in the European Parliament might not reflect political power realities across the Member States. To test this hypothesis, more research is needed into the selection process of the members of national parliaments as speakers on the Inaugural Plenary. Second, 5 out of 27 national parliaments did not designate speakers to the Inaugural Plenary: Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Malta and Bulgaria. This might indicate that these national parliaments are not as enthusiastic about the Conference as others might be, which could have resulted in more sceptical opinions voiced at the Inaugural Plenary.

Fig. 3. Political affiliation of speakers representing national parliaments

Source: Compiled by the author.

5 out of 6 civil society representatives expressed clear integrationist views. Only Ioannis Vardakastanis, the president of the Greek National Confederation of Disabled People and Vice President of EESC Group III, expressed criticism about the accessibility of the Conference´s online platform for people with disabilities and marginalized people. This imbalance seems to be explained by the nature of the represented civil society organisations and their selected spokesperson, which will be discussed in part 5.

Interestingly, both in the groups of the Commissioners, the social partners and the EESC, no EU-sceptic views were expressed. In the Committee of Regions, only one sceptic comment was noted, again by the Polish representative.[3] This shows that these organisations are clearly biased, and not in line with the views of European citizens, as surveyed by Eurobarometer.

It remains to be seen whether this bias will be less pronounced or even exacerbated as the Conference progresses, when specific political topics will be discussed. During the Inaugural Plenary, speakers were asked to share their general expectations of the Conference, rather than to share their views on particular topics. Just like the data from Eurobarometer, I will use the data from the Inaugural Plenary as a benchmark for future, thematic sessions of the Conference.

We can draw a first conclusion: if compared to the most recent data from Eurobarometer on the Future of Europe, all categories of speakers showed a clear disproportionate support for more EU integration. This means that, based on the general sentiments expressed at the Inaugural Plenary, we can expect the Conference to come forward with ambitious compromises asking for more integration at EU level. This is clearly not in line with the general views and preferences of European citizens. This risks to further alienate citizens from the European project, and deepen, rather than close the chasm between the EU institutions and European citizens.

National distribution per category of speakers

I will focus on only 2 categories: MEPs, and national parliaments. Other categories had either too few observations to extrapolate meaningful conclusions, or have a fixed distribution, i.e., the Council and the citizens’ representatives (one per Member State).

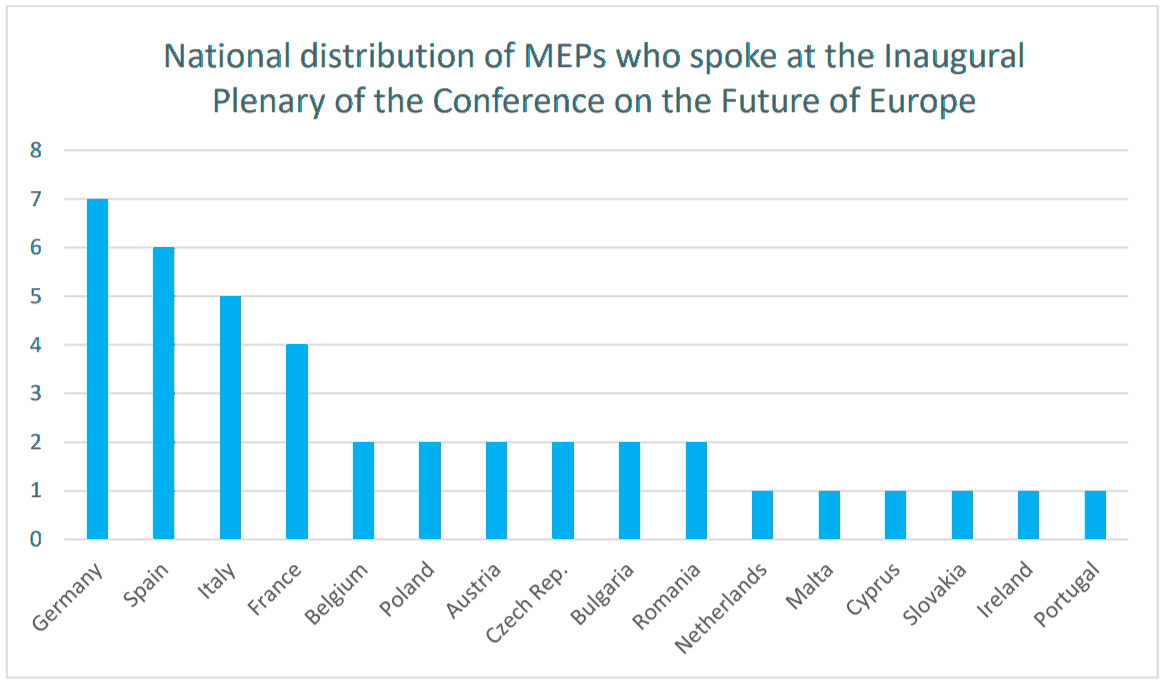

Fig. 4. Distributions of MEPs across Member States

Source: Compiled by the author.

When looking at the speakers list of MEPs (Fig. 4), we see that only 16 Member States were represented. 11 Member States were not: Luxemburg, Denmark, Slovenia, Croatia, Hungary, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Finland and Sweden. Note that there wasn´t a single speaker from the Nordic Member States or the Baltics. That is a strategically and politically very important cluster in the EU that was not represented by MEPs at the Inaugural Plenary. This imbalance needs to be addressed by the European Parliament´s Delegation to the Conference.

Secondly, we can infer that the distribution of speaking time according to the proportions of the political groups in the European Parliament only very imperfectly reflects the relative population sizes. Indeed, bigger Member States, with bigger national delegations to the European Parliament, have a higher number of speakers. Germany, Spain, Italy and France account for over half of the speakers of the MEP contingent. However, Poland was only represented by two MEPs,[4] just like smaller countries such as Belgium, Austria and the Czech Republic.

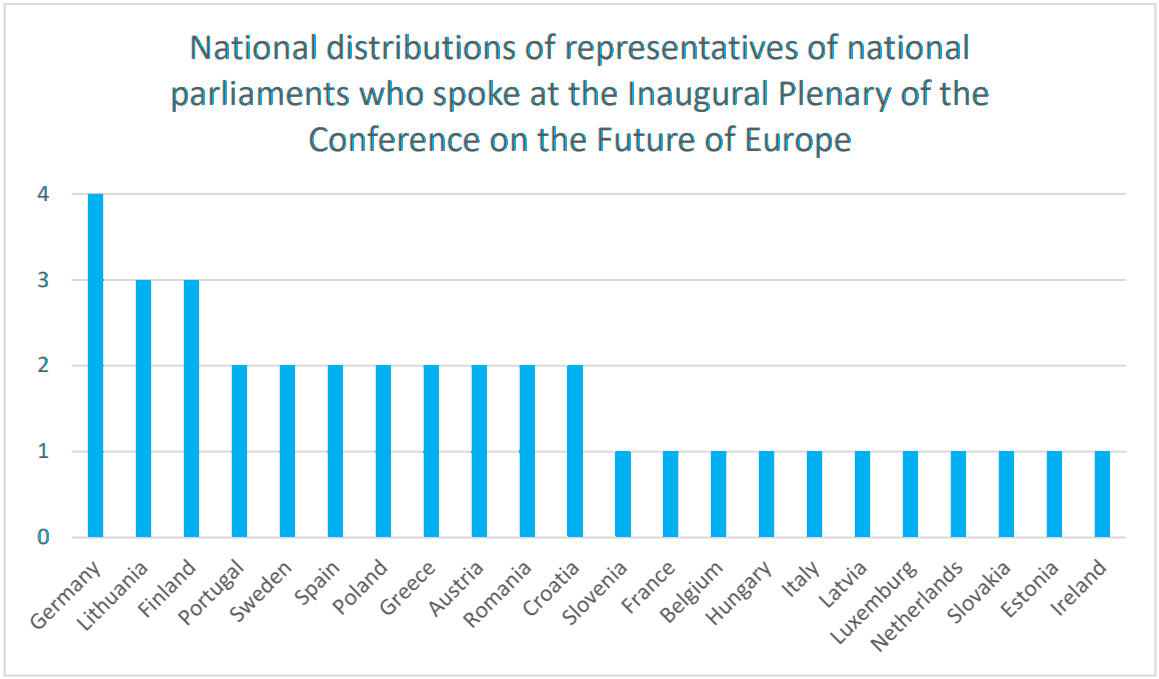

Fig. 5. Distributions of national members of parliament across Member States

Source: Compiled by the author.

When looking at the speakers list of MEPs (Fig. 5), we see that 22 Member States were represented. 5 were not: Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Malta and Bulgaria. Note that Denmark is the only Member State that had neither a MEP nor a national representative speaking at the Inaugural Plenary.

This is significantly better than the national distribution of MEPs, even though more MEPs took the floor than representatives of national parliaments. The data also clearly shows that, although national representatives’ political representation is roughly in line with the relative strength of the political groups in the European Parliament, their numerical representation clearly doesn´t correlate with the total population of the Member States: smaller countries such as Finland and Lithuania each had 3 speakers from national parliaments, compared to only 1 from major Member States like France and Italy. All the more striking is the fact that there were no MEPs from Finland or Lithuania taking the floor.

This could indicate that there is more national ownership in these countries of the discussion on the Future of Europe. Further research into the selection process of the national representatives is needed to test this, and other hypotheses.

We can infer from this that although MEPs representation at the Conference is more likely to guarantee speaking time to the larger member states, the national representation seems to guarantee a broader range of views from more member states, including smaller ones. This could trigger the perception among European citizens that the European Parliament is mainly pursuing the interests of the larger Member States, paying less or no attention to the interests of smaller Member States. Although the data seems to hint that representatives of national parliaments tend to be less outspoken in both an integrationist or EU-sceptic way, and hold more middle-of-the-road positions, the political affiliations of national representatives are largely in line with those of MEPs (Fig. 6). Interestingly, relative to the size of their group, the ECR was overrepresented at the Inaugural Plenary, with more speakers from both the European Parliament and national parliaments than ID and the Greens.

Fig. 6. Distribution of MEPs and representatives of national parliaments across political affiliation

Source: Compiled by the author.

Review of citizens’ representatives

Citizens were represented by 27 speakers (one per Member State) at the Inaugural Plenary. I took a closer look at the speakers. A number of problems arise:

First, at least 15 speakers (55.6 percent) were representing non-profit organisations or organisations close to government, such as think thanks, national or international youth organisations, youth parliaments or similar organisations. The first speaker is the president of the European Youth Forum, an organisation that received a 59.5000 EUR grant from the European Parliament in 2020.[5] Another speaker is the director of an umbrella organisation that advocates for nongovernmental sector interests which received a European Parliament grant of 39.950 EUR in 2020, and is an official European Citizens’ Initiative ambassador.[6] Three speakers were full professors, including two Jean Monnet Chairs.[7] The Jean Monnet Association received a 50.000 EUR grant from the European Parliament in 2020.[8] One speaker is the CEO of a government agency that provides information on EU related matters, including funds, aimed at “assisting non-profit organisations to benefit from EU funding opportunities”.[9] The Finish citizens’ representative is presented on the website of the Finnish government as someone who “aims for civil society to participate actively in the conference”.[10] One speaker is leader of a regional chapter of the European Rural Youth, an organisation that received a European Parliament grant of 70.705 EUR in 2020.[11]

One citizen is a former MEP[12] who was shortlisted in 2011 for the prize of “the best Member of the European Parliament”, while another citizen is politically active in the Swedish Center Party (Renew).[13] At least two citizens are militantly active in organisations promoting further integration, of which one has outlined her vision for combatting EU-sceptics in several interviews.[14]

Only 4 citizens seemed to work in the private sector. However, one of them received 6 million euros in EU funding in 2011.[15] This EU funding might have influenced his perception of the EU in an integrationist direction.

Looking at the background of the citizens, it seems to be they are more representative of civil society than of citizens, many of which received lavish grants from the European Parliament in 2020. Only 4 citizens could not be traced back to non-profit organizations or other pressures groups. This is serious problem that needs to be addressed by the Executive Board of the Conference. Either by merging the categories civil society and citizens, or by re-thinking the selection procedure for citizens, making sure fewer citizens who are also active in civil society organisations, and more genuinely independent people, including people working in the private sector, are able to express their views. If not, more European citizens following the Conference might feel disenfranchised and not represented by the citizens that were selected to represent them. I also refer to the aforementioned Eurobarometer, which found that 51 percent of respondents prefer ordinary citizens/people (like them) to participate to the Conference on the future of Europe. I believe it is safe to say that people active in organisations receiving lavish funds from the European Parliament do not fall under this category.

Review of civil society organisations

Civil society organisations were represented by 6 speakers at the Inaugural Plenary. I took a closer look at both the speakers and the organisations they represent. Three problems arise:

First, 4 out of 6 speakers seemed to represent the same organisation: both Patrizia Heidegger,[16] Petros Fassoulas,[17] Yves Bertoncini[18] and Anna Echterhoff[19] represented either the European Movement International (EMI) directly, either a national chapter of the organisation, or an organisation under the EMI umbrella. This at least creates the impression that the EMI, which is an organisation promoting further EU integration, has quasi-monopolized the speaking time for civil society representatives. The European Movement received a European Parliament grant of 185.000 EUR in 2020.[20] This explains the overrepresentation of integrationist views expressed by the speakers of this category compared to the benchmark of Eurobarometer. Furthermore, both the EMI and the European Civic Forum were also represented in the category citizens,[21] blurring the lines between both categories. Interestingly, the ‘citizen’ Noelle O’Connell is the CEO of the European Movement Ireland, which received a grant from the European Parliament of 56.688 euro in 2020. If European citizens became aware of this, it may undermine the legitimacy of this category altogether. Possible solutions to solve this problem are

- excluding the EMI as an umbrella organisation, but allowing their member organisations;

- allowing only 1 speaker to take the floor on behalf of EMI and its member organisations;

- Limit EMI speakers to one category of speakers.

Second, the backgrounds of some of the speakers may give rise to doubts. Patrizia Heidegger used to be a parliamentary advisor to the German Greens,[22] and it is unclear whether the European Environment Bureau (EEB) is a civil society organisation or an environmental lobby organisation. This blurs the line between political activism, and representing an organisation with a certain specific expertise. Ioannis Vardakastanis officially represented the Greek National Confederation of Disabled People, but also happens to be the vice-president of Diversity Europe (Group III) in the European Economic and Social Council (EESC),[23] while his president, Seamus Boland, took the floor in the EESC category.[24] Yves Bertoncini, who took the floor as the president of the European Movement France, also happens to be a lobbyist for APCO Worldwide, a large lobbying firm, a former director of the Jacques Delors Institute and a former professor at the College of Europe in Bruges.[25] His status as a lobbyist, which is not disclosed on his bio on the EM France website, might further undermine the legitimacy of this category in the eyes of the European citizens. Furthermore, the fact that another professor at the College of Europe has taken the floor as a citizen[26] blurs the lines between both categories. Possible solutions to solve this problem are:

- Disclose all past and present activities of participants;

- Exclude speakers who work as lobbyists or can be traced back to political parties;

- Communicate clearly that the category civil society also includes lobbyists.

Third, since 5 out of 6 speakers can be traced back to very large umbrella organisations of NGOs, it could be interesting to attribute more speaking time to civil society organisations which are independent, and to those with a more EU-sceptic profile, which could counterbalance the inclusion of the eurofederalist Union of European Federalists. This way, the views expressed in this category will become more diverse and better aligned with the views in society as a whole, based on the Eurobarometer benchmark.

I kindly invite the Executive Board of the Conference to address these issues and discuss possible solutions to solve them.

Conclusions and suggestions

From this paper, we can identify four mayor problem areas which call into question the legitimacy of the Inaugural Plenary of the Conference on the Future of Europe and suggest some solutions, to avoid these problems in the future sessions.

First, the Inaugural Plenary featured a clear majority of integrationist speakers, which is not in line with the latest available data from Eurobarometer on support for further institutional integration at EU level. This finding is consistent across all categories of speakers. It needs to further investigated if this is the result of a selection bias. If so, the Conference needs to publish this disclaimer, and duly inform the public, in order to avoid disenfranchisement

Second, there is a clear disequilibrium in the geographic spread of speakers from the European Parliament and national and regional parliaments. While the European Parliament speakers only come from a limited number of Member States, and are most likely to be from larger Member States, the speakers from national parliaments represent more Member States, and are more likely to represent smaller Member States. Amongst the speakers from the European Parliament there wasn´t a single speaker from the Nordic Member States or the Baltics. The European Parliament´s Delegation to the Conference needs to address this issue and ensure a better geographical distribution of speakers.

Third, the majority of speakers labelled as citizens, are engaged, and sometimes even gainfully employed in civil society organisations, some of which were also represented in the category civil society organisations, blurring the difference between these two categories of speakers. Possible solutions could be either to merge the two categories into one category “citizens and civil society”, or to better scrutinize the citizens’ representatives for their political and other associations. The publication of their resumes could help would at least ensure transparency. I also suggest to include more unaffiliated citizens, and people from the private sector, preferably from companies which did not receive EU funding. Ideally, former MEPs and members of national parliaments would be excluded from this category. Furthermore, university professors and people associated with government organizations, would rather fit the category civil society, given their expertise. In any event, all participants should be required to disclose all funding they have received from public sources in the last 15 years.

Fourth, most civil society organisations represented at the Inaugural Plenary have a clear integrationist agenda, are intertwined with each other, and seem to lack true diversity of opinion. Both the EMI and the Civic Forum were represented in both citizens and civil society organisations. More than half the civil society representatives belong to the EMI umbrella organisation, and it is unclear if organisations such as the EEB are lobby organisations or civil society organisations. It is especially worrying that active lobbyists are being presented as representatives of civil society. I suggest to limit the speakers’ list to 1 EMI representative, either from the international board or one of the members, speaking on behalf of the entire organisation. This person should only take the floor in the category civil society, not in the category citizens. I also suggest to fully disclose all past and present activities of participants, and either to exclude lobbyists from the speakers’ list, or to explicitly disclose that lobbyists are also represented in this category.

I hope this paper helps the Executive Board of the Conference and the European Parliament´s Delegation to the Conference in improving the workings and the transparency of the Conference. I tried to formulate concrete solutions to evidence-based problems, that might help avoiding disenfranchisement of European citizens with the Conference, and therefore with the future of Europe.

Notes

[1] Special Eurobarometer 500, Future of Europe, October-November 2020.

[2] Pascal Durand (FR, Renew), Daniel Freund (DE, Greens), Fabio Massimo Castaldo (IT, NI).

[3] Olgierd Geblewicz, EPP: The EU need to be revamped and it should “start” working for and with the people. Democratic scrutiny needs to be improved and the EU should become less bureaucratic (paraphrased).

[4] Zdzisław Krasnodębski (ECR), who voiced a sceptic opinion, and Danuta Huebner (EPP), who voiced an integrationist opinion

[5] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/contracts-and-grants/en/grants/ex-post-publication

[6] Kristine Zonberga is director the Civic Alliance Latvia (CAL), the largest umbrella organisation that advocates for non-governmental sector interests. She is also board member of the European Civic Forum and Chair of the Executive Board of the Active Citizens Fund, as well as official European Citizens Initiative Chair. CAL received a European Parliament grant of 39.950 EUR in 2020 for ‘Preparing the ground for the Conference on the future of Europe’. See: European Parliament (2021). Contracts and Grants. Ex post publication. URL: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/contracts-and-grants/en/grants/ex-post-publication

[7] George Pragoulatos, professor of European Politics at the College of Europe in Bruges since 2006, and advisor on European affairs to the Greek president. Francisco Aldecoa is professor of political sciences and Jean Monnet Chair. Alina Bargaoanu is professor, dean and former acting rector, advisor to the Romanian government, and Jean Monnet Chair

[8] European Parliament (2021). Contracts and Grants. Ex post publication. URL: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/contracts-and-grants/en/grants/ex-post-publication

[9] Mandy Falzon.

[10] Ninni Norra has been chair of the local chapter of the European Youth Parliament, and of the Finnish National Youth Council Allianssi: https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/-/10616/ninni-norra-selected-as-finland-s-citizenrepresentative-to-future-of-europe-conference

[11] Valentina Gutka is leader of the Lower Austrian chapter of the European Rural Youth. Its funding by the EP in 2020 can be found here: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/contracts-and-grants/en/grants/ex-post-publication .

[12] Regina Bastos, former MEP (1999-2004 and 2009-2014), former member of Parliament (2005-09).

[13] Elsie Gisslegard is active in the Swedish Center Party for almost 4 years, and is currently member of the national board of the Youth Section. https://se.linkedin.com/in/elsie-gissleg percentC3 percentA5rd-533151167?trk=peopleguest_people_search-card .

[14] Gergana Passy is founder and president of the Bulgarian chapter of PanEuropa, which promotes the idea of further European integration. Stephanie Hartung is a Frankfurt-based lawyer and co-founder of the Pulse of Europe Movement, a pro-EU campaign during the latest European elections, founded in reaction to the election of Donald Trump and Brexit. Her ideas are widely reported on the internet and through media outlets.

[15] Marko Plesco. His project OPAC (Optimization of Particle Accelerators) received 6 million euros in EU funding, according to his linkedin page: https://si.linkedin.com/in/markplesko

[16] Patrizia Heidegger represented the European Environment Bureau (EEB), which is a member of the EI: https://europeanmovement.eu/member/european-environmental-bureau-eeb/

[17] Petros Fassoulas is the Secretary-General of the EMI.

[18] President of the European Movement France, the French chapter of the EMI: https://europeanmovement.eu/member/european-movement-france/

[19] Anna Echterhoff is the Secretary-General of the Union of European Federalists (UEF), which is a member of the EMI: https://europeanmovement.eu/member/union-of-european-federalists-uef/ . The Young European Federalists received a grant from the European Parliament of 123.480 EUR in 2020 for a project called ‘Next Chapter Europe – Youth voice on the Conference for Future of Europe’, while its Bavarian chapter received a grant of 6824 EUR to organise a simulation of the European Parliament. See: European Parliament (2021). Contracts and Grants. Ex post publication. URL: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/contracts-and-grants/en/grants/ex-post-publication

[20] European Parliament (2021). Contracts and Grants. Ex post publication. URL: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/contracts-and-grants/en/grants/ex-post-publication

[21] Noelle O´Connell is the CEO of the European Movement Ireland since 2011, Francisco Aldecoa is member of the European Movement Spain. Kristine Zonberga is board member of the European Civic Forum.

[22] EEB (2021). Who we are. Staff. URL: https://eeb.org/who-we-are/staff/

[23] EESC (2021). Members. URL: https://memberspage.eesc.europa.eu/Search/Details?personId=2026887&onlyActiveMandate=True&isMinimal=False

[24] EESC (2021). Members. URL: https://memberspage.eesc.europa.eu/Search/Details?personId=2028494

[25] APCO (2021). Yves Bertoncini. URL: https://apcoworldwide.com/people/yves-bertoncini/

[26] George Pragoulatos.