_ Dr. Evgeny Vinokurov, chief economist, Eurasian Development Bank and Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development. Moscow, 7 December 2021.

The Eurasian Development Bank has published a new report. The research introduced the idea of a Eurasian transport framework that would offer numerous benefits to the EAEU countries. The EDB analysts assessed the potential of the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) in the context of emerging opportunities. These include the EAEU’s greater engagement with India, Iran, and other countries in South Asia and the Persian Gulf, the significant potential for linking the INSTC with latitudinal transport routes, accelerated digitalization, and the prioritization of the climate agenda.

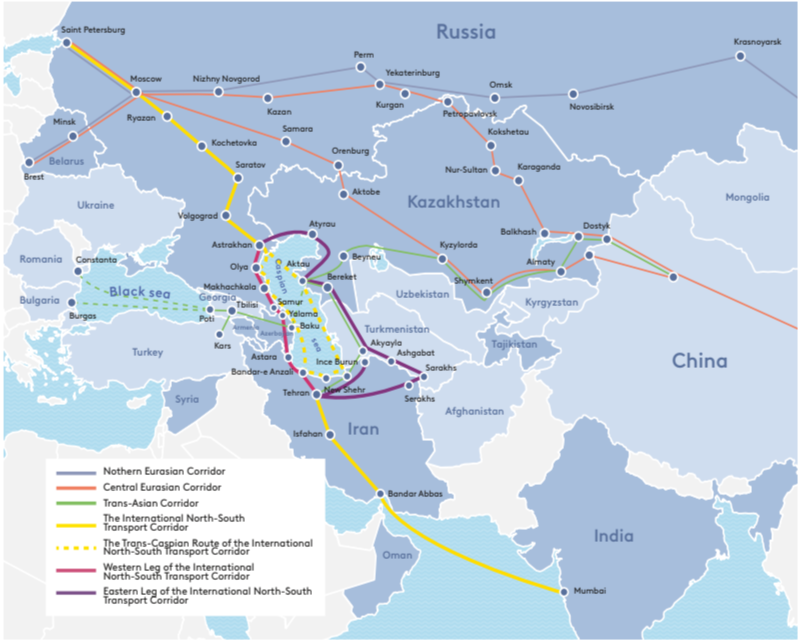

The multimodal INSTC connect the Nordic countries and the north-western part of the EAEU to the Gulf and Indian Ocean states via the Caucasus and Central Asia (Fig. 1). The corridor includes rail, road, air, sea, and river transport infrastructure and has three main routes: 1) the Western route running along the western coast of the Caspian Sea through Russia and Azerbaijan; 2) the Eastern route along the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea through Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan; and 3) the Trans-Caspian one that uses ferry and container lines across the Caspian Sea.

Figure 1. INSTC – meridional corridor of the Eurasian transport framework

Source: EDB.

The main advantage of the INSTC compared to the other routes, including the sea route through the Suez Canal, is that it halves delivery times. For example, it takes 30 to 45 days to deliver cargoes from Mumbai to Saint Petersburg by the traditional route through the Suez Canal, while the INSTC land route delivery times may vary from 15 to 24 days. Moreover, using the Eastern route of the corridor that runs through Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan can reduce delivery times to 15–18 days.

Rail transport ensures a minimal carbon footprint, which is an important competitive factor in freight transportation along the INSTC. Redirecting freight traffic from sea to rail as part of the INSTC would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 25 percent because of cutting the transportation distance. In practice, the organization of international transport corridors in Eurasia requires a combination of rail and road transport as part of an integrated approach to building efficient logistics.

The need for an alternative North–South multimodal corridor has been confirmed in the during the COVID-19 pandemic, including the Suez Canal blockage by the Ever Given container ship in March 2021. These resulted in global delays of maritime deliveries as well as uncertainty in the functioning of the logistics chains that has led to a surge in sea freight charges. In this context, the demand for rail transport on the Eurasian continent has grown, including due to the stability of single rail tariffs, thus signalling the need for an additional freight channel. The success of land corridors is also confirmed by the fact that rail container traffic on the China–Europe axis has increased from 7,000 to 547,000 twenty-foot equivalent (TEU) containers over the past ten years.

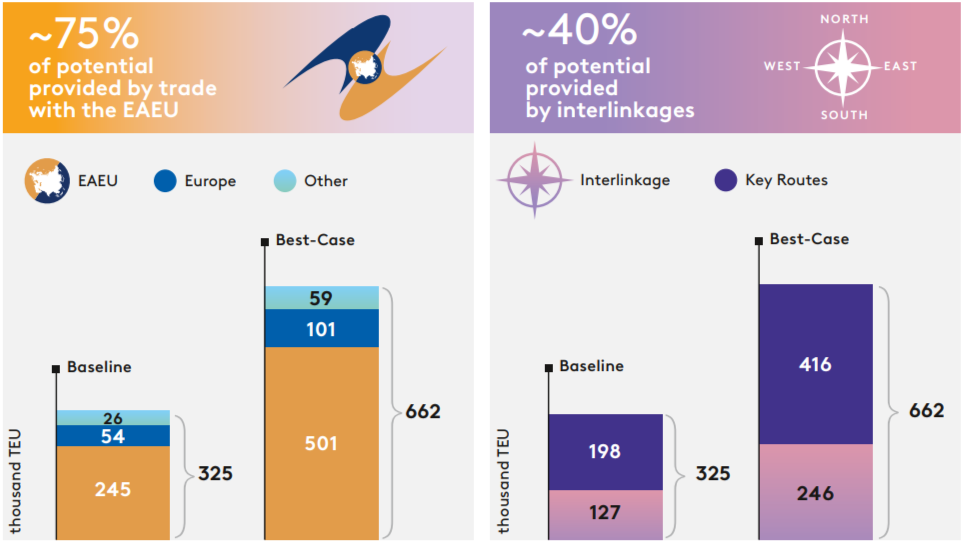

Our bank analysts highlight the significant potential for container traffic along the INSTC routes, which could range from 325,000 to 662,000 TEU (from 5.9 to 11.9 million tonnes) by 2030, depending on the scenario (currently 21,000 TEU). The development of freight transport via the INSTC is of significant interest to the EAEU member states, which account for 75 percent of potential container traffic (Fig. 2a).

The effect of linking the INSTC with the Eurasian latitudinal transport corridors could provide 127,000–246,000 TEU, or up to 40 percent, of the total container traffic potential (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2. a. (left) Potential Container Traffic through the key INSTC routes in 2030 (thousand TEU)

Figure 2. b. (right) Contribution of the interlinkages to the INSTC container traffic structure in 2030 (thousand TEU)

Source: EDB.

The main categories of containerized commodities transported along the INSTC are food (21.2 percent), metals (16.6 percent), wood, wood products, and paper (9.5 percent), machinery and equipment (8.3 percent), and mineral fertilizers (4.9 percent). The report estimates that the potential volume of non-containerised freight may reach between 8.7 and 12.8 million tonnes by 2030, mainly due to the transportation of grain crops. As a result, by 2030 the aggregate potential INSTC freight traffic, including the two types of product categories, containerized and non-containerised cargoes, is expected to reach 14.6–24.7 million tonnes.

Tariff and non-tariff barriers constrain the potential expansion of INSTC freight traffic. Possible challenges faced by the INSTC in its progressive development include the lack of a single tariff, uncoordinated transport policies of the member countries, international sanctions, lack of harmonized international transport standards and border-crossing procedures, missing links, and corridor bottlenecks. Accordingly, successful enlargement of the INSTC’s potential hinges on expansion not only of the corridor’s “hard” infrastructure, but also of its “soft” infrastructure.

The reduction of export costs associated with border compliance in states participating in the INSTC Agreement, from the current USD 376.12 to USD 79.65 (EU average), is associated with the increase in their foreign trade by 5.9 percent (USD 59.08 billion) compared to 2019. The reduction of export time associated with border compliance in states participating in the INSTC Agreement, from the current 51.33 hours to 7.48 hours (EU average), is associated with the increase in their foreign trade by 52.6 percent (USD 526 billion) compared to 2019. Deployment of intelligent transport systems and digitization of international multimodal transport and logistics using CIM/CMGS and CMR electronic waybills, eTIR carnets, and satellite navigation systems has a beneficial impact on foreign trade in the states participating in the INSTC Agreement, and can open up new opportunities for simplification of border-crossing procedures, reduction of cargo delivery times, and improvement of the INSTC safety record.

The unique INSTC route creates opportunities to link with latitudinal transport corridors running from East to West. The ultimate goal is to develop a Eurasian transport framework – a network of interconnected East–West and North–South corridors that will generate additional freight flows through synergies and provide landlocked countries with access to markets. This will help to cut export costs, develop new production niches, and realize the region’s transit potential. As the Eurasian transport corridor reaches out to China, India and the European Union, it can become a material foundation for implementing the idea of a Greater Eurasia.

Additional freight flows can be ensured by achieving “seamless” transport connectivity through digitalization and improved soft infrastructure. The implementation of intelligent transport systems and the digitalization of international multimodal transport and logistics using e-CIM/CMGS and e-CMR electronic waybills, e-TIR carnets, and satellite navigation systems has a beneficial impact on foreign trade in the countries participating in the INSTC Agreement. It can open up new opportunities for simplification of border crossing procedures, reduction of cargo delivery times and transport costs, and improvement of the INSTC safety record.

*The full report can be downloaded in Russian here.