_ Sergei Aleksashenko, Oleg Buklemishev, Oleg Vyugin, Vladimir Gimpelson, Boris Grozovsky, Evsei Gurvich, Sergei Guriev, Ruben Enikolopov, Oleg Itskhoki, Natalia Orlova, Kirill Rogov, Konstantin Sonin. Liberal Mission Foundation. Moscow, 2021.*

Current status quo: stagnation 2.0

The current state of the Russian economy can be defined as long-term stagnation. Even if we exclude the 2020 Covid year, the average annual growth rate of the Russian economy from 2009 to 2019 was 1 percent, and over five years (2014-2019) it was only 0.8 percent.[1]

Such rates are significantly lower than the growth rates of countries with a similar level of development (countries with an upper middle income: 4.6 percent in 11 years and 4 percent in five years), the average annual growth rates of the world economy (2.5 percent and 2.8 percent, respectively) and even below the growth rates of high-income and developed economies, which typically grow much more slowly than developing economies (1.5 percent and 2.1 percent, respectively, in both groups).

This means that Russia’s share in the global economy has been declining, the gap from developed countries has increased rather than decreased, and in the ranking of world economies in terms of income, Russia has fallen down.

In terms of GDP per capita, calculated at purchasing power parity, Russia from 2009 to 2019 lagged behind seven countries — Latvia, Lithuania, Malaysia, Panama, Poland, Romania and Seychelles.[2] The same indicator (GDP per capita based on PPP) for Kazakhstan in 2009 was 89 percent of the Russian one, and in 2019 it was already 97 percent.

We also note that in 1977-1985, i.e., in the period of the history of the USSR, which was called “stagnation”, the average growth rate of the economy was, according to modern calculations, 1.6 percent per year, i.e., were in two times higher than those observed during the last 6-7 years.[3] Thus, “stagnation 2.0” is not a metaphor, but a statistical statement.

Despite such a sad state of affairs — a decade actually lost for economic development — there is practically no public discussion in Russia about its causes and possible ways to return Russia to a growth trajectory today.

The theme of economic growth, which sounded powerfully in the official rhetoric of Putin’s first decade (“doubling the GDP in ten years”), has practically disappeared and has been replaced by the bureaucratic construct of “national projects” — arbitrarily set benchmarks and investment goals, which, moreover, are periodically adjusted according to deadlines and parameters, or simply remain unfulfilled.

So, the goals of the May 2012 presidential decree on increasing the accumulation rate to 27 percent and labour productivity by 1.5 times by 2018 remained unfulfilled, and a number of goals that in Putin’s May 2018 presidential decree were designated as goals for 2024, in July 2020 these goals were assigned to 2030.[4]

However, even the implementation of individual “national projects” says little about the real state of the economy. This is somewhat reminiscent of the situation in the Soviet planned economy: the command method of management made it possible to concentrate maximum resources on priority areas and achieve voluntaristically set ambitious goals (for example, “overtaking the United States in steel production”), while depriving other (in particular, innovative) sectors of resources and, as a result, increasing the overall imbalance of the planned economy.

Redistribution model of “stagnation stability”

Today, the Russian government not only lacks a growth strategy, but even lacks the appropriate goal setting. The current economic policy puts forward “stability” as an unconditional priority, which, from an economic point of view, is a model of redistribution of resource rent and income from economic activity that has developed over the past decade and corresponds to the interests of the political elite, a number of Russian business sectors and certain groups of the population.

In this sense, the refusal to focus on economic growth in Russia in the 2010s should be considered a rational choice.

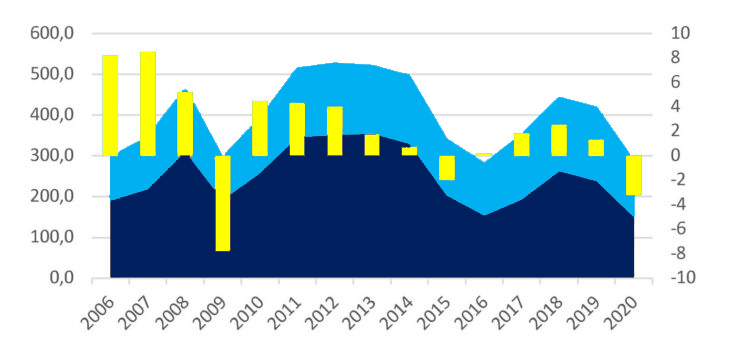

Chart 1. Export earnings and growth rates of the Russian economy (2006 – 2020)

Data: Light blue (left axis): Hydrocarbon exports in bln USD. Dark blue (left axis): Non-hydrocarbon exports in bln USD. Yellow (right axis): GDP growth in percent. Sources: Central Bank of Russia (according to the methodology of the balance of payments), World Bank.

This model is based on a relatively high level of income from the export of raw materials (primarily energy carriers, whose share in exports was 50-70 percent in 2010-2020). When these incomes declined, there was a decline in production and a contraction of the economy; when they recovered, the economy returned to growth (with a fading effect), offsetting the previous contraction and only slightly exceeding previous highs (see Chart 1).

At the same time, the “stability of stagnation” was maintained through a number of redistributive mechanisms and effects.

First, during periods of favourable market conditions, export earnings were not partially used to stimulate consumption or re-equip the economy but were saved in case of a significant loss in unfavourable periods: this made it possible to mitigate external shocks, but at the same time avoid restructuring businesses and the economy in as a whole in the conditions of resource rent reduction.

Secondly, there was a redistribution in favour of the export sector: since 2013, export volumes have grown by 15 percent, while GDP has grown by only 3 percent against the backdrop of a sharp decline in investment by 9 percent.

Thirdly, there was a redistribution of investment resources from the private sector to the public sector: with a stable level of investment in fixed assets of 22 percent, large investment projects patronized by the authorities were carried out with the participation of private and state capital; such a strategy made it possible to “pull” financial resources in the direction of the implementation of state projects; the unfavourable investment climate was compensated by manual tools to support investment activities tailored to a small number of large projects.

Fourth, there was an intensive redistribution of incomes of the population: despite the fact that, in general, these incomes decreased by 10 percent in 2020 compared to 2013, wages in real terms increased by 11 percent, i.e., income from property, entrepreneurial activity and incomes in the informal sector “redistributed” in favour of the “official” wage sector (state employees and corporations) with stable levels of profit shares and labour costs in the economy.

Fifth, there was a redistribution in favour of the domestic producer in the consumer sector (import substitution policy): the share of imports in retail trade decreased from 36 percent to 28 percent in the food segment from 2013 to 2020 and from 44 percent to 39 percent in the non-food segment. This effect, however, is a consequence not so much of industrial policy (including sanctions against European products), as of the devaluation of the ruble: the average wage at the current exchange rate was USD 940 in 2013, and USD 650 in January 2021.

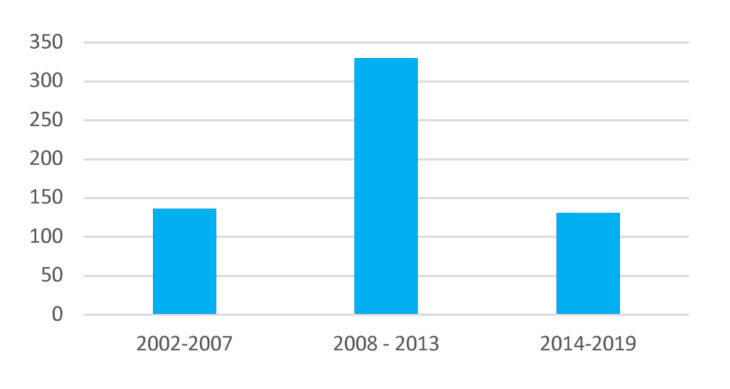

The formation and strengthening of the redistributive model was facilitated by the fundamental focus on economic isolationism, motivated by the course of foreign policy confrontation. As a result, since 2014 there has been a sharp decline in the share of foreign direct investment and an increase in sanctions barriers that impede the transfer of capital and technology (see Chart 2).

Chart 2. Foreign direct investment in the Russian economy (2002 – 2019) billion USD

Data: Central Bank of Russia (balance of operations of the balance of payments).

The economic task of the current model is to extract the maximum profitability from the raw material segments and form a financial cushion on the basis of these incomes, which can be used by the state for redistributive purposes.

The beneficiaries of such a model are companies that have access to investment resources concentrated in the hands of the state, businesses oriented towards domestic consumption and benefiting from reduced competition in the domestic market, and in general the public and corporate sectors in the labour market.

At the same time, such a model is unfavourable for the most active part of society – young people, qualified specialists, an educated class, companies in the technology sector with export potential. However, it is these groups in the current political order that can least of all influence decision-making and the choice of an economic development model.

Thus, in the current Russian model, we can observe a symbiosis of isolationism, dirigisme and extended political restrictions that ensure its “stability”, a suboptimal balance of stagnation.

Stability of the model and barriers to growth

The described economic model creates serious restrictions for economic growth and at the same time has significant stability. The main constraints to growth here are:

- “Nationalization of commanding heights” in the economy, which occurs not so much due to formal state control over assets, but due to the crowding out of private investments (the conditions for which look unfavourable) by state ones and due to the nationalization of the financial sector.

- Unfavourable legal environment and arbitrary law enforcement against the backdrop of technical and regulatory improvements in the business environment: the risk of becoming the object of administrative arbitrariness is generally lower, but the risk of becoming the object of criminal prosecution and ending up in prison is higher.[5]

- A trend towards economic and technological autarky, the growing isolation of the country in terms of attracting technology and capital.

- Declining quality of human capital.

- The lack of institutions to protect the interests of various segments of private business, the corruption-contractual nature of the distribution of preferences and state resources, and, as a result, the low competitiveness of many domestic markets.

- The preservation of inefficient industrial enterprises and projects that enjoy stable support from the state.

- The costs of excessive political control and “geopolitical priorities”: bloated staffing of law enforcement agencies, excessive regulation and control of education, the non-profit sector and the Internet, restrictions on investment for foreign companies, etc.

Despite the obstacles to economic growth and market allocation of resources created by this model, according to most experts, it is quite stable in the medium term due to stable external demand for raw materials, combined with free domestic prices and the exchange rate, which allow absorbing external shocks, associated with changing global conditions.

The stability of the model is also facilitated by the reliability of the patron-client networks that have developed over the 20 years of Vladimir Putin’s rule in the business environment and the system of state bureaucracy.

Finally, a change in the model – a turn to an open economy, a reduction in subsidies for inefficient projects, and a limitation of the redistributive practices and effects described above – is not in the interests of a fairly wide range of businesses and population groups, for whom such a turn will bring (at least in the short term) costs and uncertainty.

At the moment, Russia has entered the second decade of stagnation (“Stagnation 2.0”), while there are no serious incentives or coalitions interested in changing the “redistributive” model.

This situation, however, does not look unique: over the past 100 years, one could observe several examples of states that for many decades reduced their share in world GDP and widened the gap from the most developed countries (for example, in the early 1930s, GDP by per capita in Argentina was 70 percent of the US level, and in the late 2010s – 35 percent).[6]

At the moment, the Russian authorities do not show the slightest intention to evade this inertial scenario (the “Stagnation Comfort” scenario) and intend to make efforts to maintain the “stagnation balance”, relying on internal reserves.

To do this, in the coming years, they will need to (1) achieve intensification of labour without adequate compensation and/or (2) mobilize private capital to meet the investment objectives set by the government. Attempts to withdraw corporate profits for centralized investment are already observed in the activities of the government.

In addition, funds from the National Wealth Fund (NWF) can be used to accelerate or maintain a minimum growth rate. At the current level of oil prices, the National Wealth Fund can replenish 180-200 billion rubles monthly, these funds can be spent on investments, which, all other things being equal, can give about 1 percent of additional GDP growth.[7]

The possibility of easing monetary policy in order to stimulate growth currently looks extremely unlikely – “stability” remains a priority, but in the event of a significant deterioration in the environment or the realization of other risks, such a reversal cannot be ruled out in the future.[8]

System challenges to the “stagnation equilibrium”

There are factors of serious vulnerability of the existing “stagnation equilibrium” that can make it difficult to maintain it over the coming decade or create significant (and even critical) risks for the economy and social stability in the next 10-15 years.

First of all, revenues from the export of hydrocarbons are highly likely to decline significantly this decade. If in 2011-2015 they amounted to 1.6 trillion USD, then in 2016-2020. they were reduced to 1 trillion. There is no reason to believe that these revenues will be higher in the next ten years – oil price growth is constrained by the growth of shale production if the price of a barrel reaches 55-60 USD, and the total capacity of world production exceeds demand. That is, Russia’s revenues from oil and gas exports are highly likely to decline this decade in the inertial scenario by at least 25 percent compared to the previous one.

The main challenges and risks of the inertial scenario include:

- The demographic anti-dividend – a reduction in the number of young people entering the labour market, and a probable overall reduction in the size of the labour force and a deterioration in its quality.

- “Black swans”: the long-term impact of the pandemic, the “accumulation” of the effect of sanctions and their possible intensification, man-made crises, etc., which lead to an additional “deduction” from the current minimum growth rates.

- Accumulating changes in the global energy balance, leading in the next 10-15 years to a change in the strategies of energy market players and a sharp long-term decline in hydrocarbon prices.

During the period of “high” growth in Russia in the 2000s almost 7 million additional workers entered the labour market ( plus 10 percent of those employed in the economy), and a significant part of them were young and educated people who replaced contingents of workers with lower productivity (the last “Soviet generation”). Up to a third of GDP growth in 1997-2011 can be attributed to this demographic dividend.

In 2008-2019 the number of employed increased by 1 percent, while the share of young people with higher education decreased by 0.5 percentage points. Over the course of the current decade, the total number of people involved in economic activity will remain in the optimistic scenario or decrease in more pessimistic ones (losses can be up to 8-10 percent), but the size of the 25-40 age group will definitely decrease by about a quarter, and the number of workers of these ages with higher education will decrease to the level of 2005-2006. This means that over the course of a decade, the demographic anti-dividend for economic growth will increase, associated with a deterioration in the structure of those involved in the economy and a likely reduction in their total number.

In such a situation, ceteris paribus, to maintain the “stagnation equilibrium” – the minimum growth rates of the 2010s – some kind of compensation associated with increased productivity and investment will be required.

Just as the demographic anti-dividend, man-made crises and other “black swans” (in particular, the growing effect of sanctions and the risks of their strengthening) will not cause immediate critical problems for the economy but may (together with a decrease in export earnings) lead to an imbalance in the redistributive model, becoming an additional deduction from the minimum growth of the economy and exacerbating the downward trend in real disposable income.

In this case, there will be a further decrease in confidence in the political and economic system on the part of various groups of the population and elites, an increase in social protests and demands (including those coming from groups of traditional support for the regime), an increase in the overall level of conflict and a decrease in loyalty in patron-client networks.

An additional risk of this gradually increasing imbalance scenario (“2020s unbalance” scenario) is a deterioration in the quality of economic regulation: today’s attempts by the authorities to freeze and subsidize food prices by managing costs and profit margins in supply chains demonstrate the logic of this risk development in “information autocracies.”

Finally, changes in the global energy balance, which will be smooth, may at some point lead to changes in the strategies of energy market players, which in turn will lead to a long-term decline in hydrocarbon prices and undermine the external source of financing for the Russian economy.

Although the expected reduction in oil consumption in the main markets of Russian exports by 2030 does not look very significant, one should take into account the serious pressure of the “climate agenda” forcing the authorities of developed countries to strengthen anti-carbon regulation (e.g. the EU “Green Deal” and plans to introduce the EU carbon border adjustment mechanism, CBAM).[9]

These efforts can have an effect that significantly exceeds today’s inertial expectations and significantly change the strategies of both investors (stimulated by political decisions to invest in “clean” energy) and oil exporters, who are reorienting from the goals of maintaining prices to the goals of maintaining market share.

Although these events are highly likely to be relegated to the horizon of the current decade, they threaten Russia with a serious economic and social crisis in the future. Changes in energy prices are often abrupt, while shortfalls in income cannot be replaced relatively quickly.

In this case, Russia will face a simultaneous contraction of public finances, a weakening of the balance of payments and the national currency, and, consequently, a reduction in the possibilities for imports, making it difficult to structural manoeuvre.

Oil rent makes it possible to compensate for the inefficiency of a number of industries for a long time; as a result, its contraction and the impossibility of further support leads to a structural crisis.

At the same time, due to high competition in international markets, strategies to partially compensate for the loss of raw material export earnings require long-term integration into production chains and product niches and long-term strategies aimed at this.

In order to compensate for the income that is expected to fall in the 2030s, it is necessary today to actively increase the export potential in sectors that can replace them. In 10 years, such embedding will be much more difficult due to increasing competition for these niches among developing countries and the devaluation of human capital advantages.

In the described scenario, the probability of which today should be assessed as significant, the second decade of stagnation (“Stagnation 2.0”) becomes a prologue to a new crisis decade in the 2030s, which will be characterized by a significant reduction in GDP and social upheavals (scenario “Crisis 2030’s”). In this case, Russia, following Venezuela, will be the country that has experienced the second structural crisis in 50 years, associated with the volatility of oil prices.

Growth strategies and the middle-income trap

Models of catching up economic development are ultimately based on two opposite strategies: the strategy of self-reliance, or the export-oriented strategy.

The economic history of the 20th century was replete with experiences of the first kind, from the radical Soviet, “Maoist” and North Korean scenarios to the market options for import-substituting industrialization (ISI) tested in Latin America in the 1950s-1980s.

Strategies of this type, while demonstrating encouraging results in the early stages, faced serious restrictions on reaching the middle-income level, when the opportunities for growth through the involvement of new resources and labour are close to being exhausted.

And, on the contrary, it was the countries that embarked early on the path of export-oriented growth that showed rare examples of the transition from the club of developing to the group of developed economies: Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong.

Today, Russia is included in the group of countries with “upper middle income”: 4,000-12,500 USD of gross national income per capita, moreover, it occupies one of the first lines in it.[10] However, this position is largely secured by income from raw material exports. At the same time, Russia does not critically lag behind developed countries in terms of human capital but seriously (critically) lags behind in terms of the level of development of industry (high-tech sectors) and the sector of related services.

The most important guideline and medium-term goal of economic development in this situation is to reduce the gap with developed countries in terms of GDP per capita.

The choice of certain strategies and the conjuncture of world markets can lead to both an increase and a reduction in this gap.

Thus, the ratio of GDP per capita in Russia to the average for developed countries (OECD countries) was 62 percent in 2009, rose to 65 percent in 2013 and fell again to 60.5 percent in 2019.

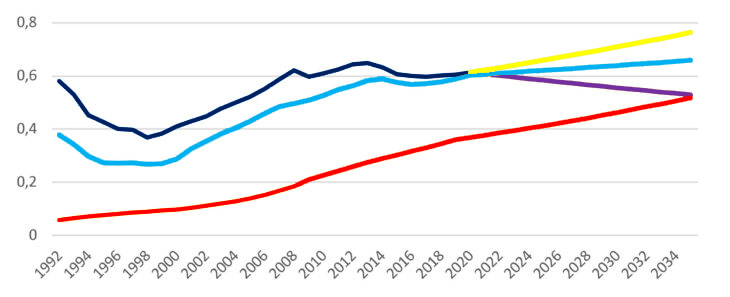

In the inertial scenario (average growth rates 1 percent per year) this figure for Russia will be by the mid-2030s already 52 percent of the OECD average, and in the intensive scenario (3.5 percent growth per year) will reach 76 percent (see Chart 3). This is the main fork of development and the price of long-term stagnation for the country in the medium term.

Graph 3. GDP per capita in Russia, China and Kazakhstan as a share of that of OECD countries (present 1992 – 2020 and forecast 2021 – 2035)

Data: Dark blue (present): Russia. Yellow (forecast): Russia – intensive scenario. Purple (forecast): Russia – intertial scenario. Light blue (present and forecast): Kazahkstan. Red (present and forecast): China. For 2020, actual GDP contraction data are used in the respective countries, the business-as-usual scenario for all countries on the graph (including the OECD reference countries) assumes that the average annual growth rates over the past 10 years will be maintained; source of data on the dynamics of GDP per capita at PPP in 1992-2019. — World Bank, for 2021-2035 — calculations of the authors.

Long-term fluctuations in GDP per capita at levels of 40-70 percent of the similar indicator in developed countries are characteristic of a number of economies (mainly using import substitution strategies at the stage of industrialization) and are called the “middle income trap”.

In general terms, this situation is the result of insufficient growth in labour productivity against the backdrop of continued growth in wages and, consequently, labour costs. As a result, the rate of return in the economy decreases, it becomes less attractive for investment, and its exports become less competitive.

In turn, it is difficult for society to come to terms with the fact that the distribution of income and the structure of the economy that developed in the past period, which seemed to have provided good results in its time, needs a deep restructuring; coalitions that form in support of the status quo use all possible means to maintain it.

In the Russian case, the situation is aggravated by the fact that the economy receives a rent from hydrocarbon exports, as a result, the level of income and business, and part of the population, is higher than that which corresponds to the level of technological development and labour productivity achieved. In the case of suppressed political competition and the lack of representation of the interests of significant groups in the political system, the situation becomes even more difficult.

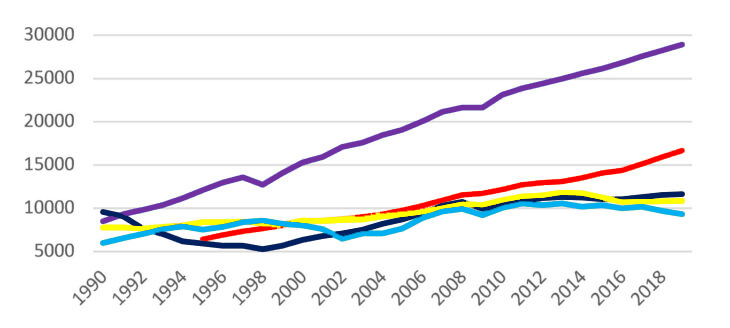

Chart 4. The middle-income trap and how to overcome it (1990 – 2020, GDP per capita)

Data: Purple: South Korea. Red: Poland. Dark blue: Russia. Yellow: Brazil. Light blue: Argentina. Gross national income per capita in constant 2010 USD. Source: World Bank (2021).

The middle-income trap is a serious problem: for decades, countries have been treading water in the corridor of 40-70 percent of the developed level (see the tracks of Russia, Argentina and Brazil in Chart 4).

In the general case, the way out of the trap is associated with overcoming the factors that give rise to it – with the growth of productivity, which means an increase in the share of high value-added goods produced by the economy.

While the general recommendations of economists in this regard are well known – strengthening property rights and regulatory neutrality to increase investment attractiveness, stimulating technology and service exports, investing in infrastructure, human capital, research and development – few governments manage to implement them.[11]

The reason lies both in the fact that strong political coalitions within the country counteract this, and in the fact that there is no universal recipe for getting out of the trap: in each specific case, it is necessary to look for those competitive advantages, relying on which the economy could compensate for the relatively high price of labour.

Competitive advantages and policy options

As a competitive advantage of Russia, one can consider, firstly, its geographical position – proximity to European and Asian markets at the same time, as well as the presence of the markets of the countries of the former USSR, over which Russia has an advantage both in terms of human capital and capital-labour ratio.

An important factor contributing to the exit from the middle-income trap and the transition to the club of developed countries is the presence of an “institutional anchor”. It is this factor that to a large extent ensured the entry into the club of the developed countries of Southern Europe and the forthcoming entry of the countries of Central Europe into it during the current and next decades. But the institutional anchor works in tandem with expanding market access to (usually wealthier) anchor countries. With all the difficulties of this process, Belarus, Ukraine and Russia could benefit greatly from the geographical and cultural-historical proximity to Europe.

Another competitive advantage of Russia is, as already mentioned, the quality of human capital at a moderate cost of highly skilled labour. The most well-known human development indices place Russia in the group of countries immediately following the developed countries, but in recent years this advantage has begun to wane.[12]

The biggest long-term problem with the current model is the decline in the quality of human capital. By the time the technological revolution takes place in the world, the quality of the bulk of the Russian workforce will not match the new skills.

As a compensatory measure, it would be possible to increase the rate of social contributions for physical labour, zeroing it in non-manual labour professions.

However, the main factor here is the demand for a highly skilled and enterprising labour force in the labour market, most experts agree. In other words, the maintenance and preservation of this advantage is directly related to the choice of one or another intesive development strategy: extensive strategies will lead to its reduction and loss.

The third competitive advantage is the large size of the domestic market, which makes Russia potentially attractive to multinational corporations. In turn, their presence in Russia leads to the transfer of technology and know-how, the improvement of corporate standards and the business environment, and opens-up opportunities for integration into value chains.

The fundamental limitations, competitive anti-advantages of the Russian economy are also well known: These are an unfavourable demographic trend leading to a reduction in the number of employees and an aging population, a rather high cost of labour, which reduces the competitiveness of Russian goods, and a legal regime unfavourable for the development of entrepreneurship, investment and innovation.

At the same time, the negative contribution of the latter factor to economic growth has been intensified in recent years due to the policy of both external and internal (access to markets and financial resources) closeness.

In general, restrictions on competition in the form of preferences for large national companies in an alliance with a non-democratic regime is not an unconditional barrier to economic growth, but only within the framework of an export-oriented model, where the task of the “national champions” of the technology sector becomes the conquest of foreign markets (the model of South Korea until the end of the 1990s).

On the other hand, an increase in the competitiveness of domestic markets may have a stimulating effect: for example, one of the important drivers of growth in China was the process of capturing part of the markets of state-owned and state-related companies by more productive private firms. However, this implies a steady restriction of preferences for such companies and the creation of equal conditions for access; moreover, this process also brings more benefits in an open economy.

In any case, it can be argued that the combination of low competitiveness of domestic markets, government preferences for affiliated companies, on the one hand, and an orientation toward an externally closed economy, on the other, is the worst possible scenario for economic development.

Faced with the need for change, political elites may prefer external openness to stimulating internal competition and the rapid destruction of preferences: such a scenario looks politically more benign.

Policies to encourage domestic competition and gradually limit preferences that distort firms’ access to resources could include:

- The stimulation of competition between regions according to the “Chinese model”.

- The “commercialization” of the state and quasi-state (state-owned companies) sectors of the economy and the gradual transfer of such companies to the “general” regime of relations with the state.

- Establishing clear horizons for the reduction and termination of state support for inefficient industries and encouraging their restructuring.

- The development of the financial sector and its denationalization.

- The restriction of legal arbitrariness and interference of law enforcement agencies in economic activity.

The consensus among economists is that modern economic growth and overcoming the middle-income trap are impossible without an open economy. The successes of autarkic models (“self-reliance”), if they have taken place, are connected with the previous stages of development; examples of dynamic economic growth for upper-middle-income countries without an open mindset simply do not exist.

Vector of optimal strategies

The main factor determining economic progress is the ability of the existing political system to unleash the nation’s internal entrepreneurial potential.

Despite the fact that the incentives to maintain the redistributive model and the comfort of stagnation are great today, the most effective manoeuvre that can put the Russian economy on a growth trajectory could be to abandon the policy of economic and cultural autarky and overcome the trend towards technological and investment isolation. The goals of economic development (getting out of the middle-income trap, narrowing the gap with developed countries in terms of GDP per capita, reducing the risks of a systemic crisis associated with falling oil prices) and the goals of Russian foreign policy are now in direct conflict.

Meanwhile, there are well-known examples in history when, in the interests of reaching a growth trajectory, governments (authoritarian governments) sharply changed their foreign policy course, formed by a powerful tradition of previous decades (South Korea under Park Chung-hee in the mid-1960s, China in the early 1980s under Deng Xiaoping).

The maximum use of competitive advantages (proximity to Europe and historical ties with it, the quality of human capital at a relatively low price of skilled labour, the scale of the domestic market), the condition of which is a return to the policy of openness, indicates the vector of optimal economic policy strategies at a given level of economic development. And overcoming the gap between Russia and developed and dynamic middle-income countries in the technological sector of industry and related services should be their main task.

Modern economic growth and technological progress are largely concentrated in international (global) value chains (GVCs). This is where the exchange of investment, technology and organizational skills takes place. The shifts that have taken place in world production and trade associated with cooperation within the framework of GVCs (which today cover up to 70 percent of world trade) have led to major changes in the strategies and goals of catch-up development.

First, the indicator of success and export orientation is now not so much the presence of “national champions” capable of conquering international markets, but the total number of firms involved in export-import operations within the chains.

And, on the contrary, as the experience of South Korea has shown, the “national champions” at this stage turn into a burden on the economy and are capable of generating economic instability.

Secondly, cooperation within chains undermines the very logic of import substitution strategies: restrictions on imports entail potential restrictions on reverse exports, and production in those segments of the chain where value added is low is not profitable for middle-income countries (due to the relatively high price of labour).

In general, the effectiveness of participation in chains is determined by the place that national firms occupy in them: the most effective is the return export of goods at the end of the chain – at the stages closest to the final consumer, this stage accounts for the main added value. At the same time, resource-based economies are predominantly characterized by direct participation in chains, i.e., the supply of raw materials at the beginning of the chains.[13]

The need to expand technology exports and better fit into global value chains is driving efforts to find and possibly subsidize “hidden comparative advantage” sectors or niches, typically adjacent to current export sectors, and expand the product baskets of existing exports.

In this context, it is necessary to mention the important achievement of Russian business, which outlined the likely area of its potential competitiveness. In a very small number of countries, local companies have been able to successfully compete even in the domestic market with American technology giants such as Google, Amazon, Facebook, Uber, Zynga. Russian private companies have succeeded (Yandex, Mail.ru, VKontakte, Ozon); their success in foreign markets is still limited, but they may have an impact on the markets of nearby countries, including in Eastern Europe and the countries of the former USSR.[14]

The more dramatic are the trends of “politicization” of this sector of a potential breakthrough and restrictions on foreign investment, which in the future will lead to its inevitable conservation.

The central task of increasing the participation of national firms in GVCs requires efforts to create the appropriate conditions and infrastructure in the following areas: (1) development of the financial sector; (2) creating favourable conditions for foreign investment; (3) development of advanced infrastructure; (4) creating conditions and incentives for innovation and export, including and above all through the strengthening of property rights and intellectual property; (5) increasing investment in human capital, as well as in research and development (including by reducing non-productive expenses).

Progress along these lines is unlikely to be rapid, but within a decade it could lead to a significant increase in the participation of Russian firms in GVCs, an increase in production and exports in the technology sector, and the development of an associated service sector.

To date, two scenarios are known for successfully overcoming the challenge of average incomes and moving into the club of developed countries: 1) the presence of an “institutional anchor”, coupled with the prospects for access to the markets of “anchor” countries (this is how the countries of Southern Europe entered this club and Central European countries will enter in the coming decades; 2) forced export-oriented growth (Asian model – Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore). For various reasons, it is impossible for Russia to implement either the first or the second scenario in its pure form, but a combination of their elements is possible. Using the geographic advantage of proximity to Europe and Asia and the advantage of human capital at a relatively low price of skilled labour, Russia could occupy a niche as an exporter of products based on European technologies to the markets of the CIS and East Asia. And using the advantages of market scale and the high quality of human capital, to expand its participation in global value chains and capitalize on regional leadership in the Internet economy.

Such a strategy does not promise a “magic breakthrough”, but if successful, it will help avoid the second structural crisis in fifty years in the 2030s associated with oil price volatility, realize and maintain existing competitive advantages and enter a new technological era with better potential and a more sustainable economic structure. The condition for the realization of such a scenario, however, is a vigorous change of priorities: a choice in favour of development priorities instead of the priorities of confrontation and autarky, i.e., a vigorous turn towards a policy of economic openness.

And, conversely, strategies of “self-reliance” are not guaranteed to achieve these goals due to the division of labour and price ratios that are taking shape in the world.

The model of exchanging exported raw materials for goods and technologies used for domestic consumption does not lead to an increase in aggregate welfare outside of periods of ultra-high resource prices and turns into crises when they end, returning the country to previous levels of income.

Sources:

[1] Here and below, unless otherwise noted: The data is taken from: World Bank (2021). World Development Indicators database. URL: https://data.worldbank.org/ | In 2009, the Russian economy fell by 7.8 percent after the global financial crisis, but this decline was reflected in the recovery growth of 2010-2011. (4.5 percent per year), so the countdown should start from 2009, not 2010 The economy finally stabilized on a low-growth trajectory in 2013-2019.

[2] According to the IMF, this pool also includes Turkey and Croatia. | IMF (2020). World Economic Outlook database. 2020. URL: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/SPROLLs/world-economic-outlook-databases#sort=%40imfdate%20descending

[3] University of Groningen (2022). Maddison Project Database 2020. URL: https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/releases/maddison-project-database-2020

[4] Gontmakher E. (2020). Social policy: pandemic stress test and social policy. Year of Covid: preliminary findings and challenges of the decade. Liberal Mission Foundation. Moscow.

[5] Russia has rapidly improved its position in the Doing business rating, rising from 120th to 28th place in 9 years. The rating takes into account standard business procedures but does not take into account legal risks. The change in Russia’s positions in the Doing business rating to a certain extent reflects not only the progress in regulation (which is taking place), but also the redistribution of power between the state and power bureaucracy. The usual news: “Moscow Prosecutor Denis Popov issued a warning to the head of a large supermarket chain about the inadmissibility of overpricing sunflower oil” (“Interfax”, March 30, 2021), fully reflects such practices of political and forceful interference in economic activity outside economic discretion.

[6] University of Groningen (2022).

[7] Putin V. (2021). Meeting on Measures to Stimulate Investment Activity- Kremlin. URL: http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/65141

[8] This is evidenced, in particular, by the recent increase in the Central Bank rate by 25 basis points. | Central Bank of Russia (2021). URL: https://www.cbr.ru/press/keypr/

[9] European Commission. (2021). A European Green Deal. Striving to be the first climate-neutral continent.URL: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en

[10] In constant 2010 USD. Russia’s figure in 2019 is USD 11,636. World Bank (2021).

[11] Agénor, P. R., Canuto, O. (2015). Middle-income growth traps. Research in Economics. | Su, D., Yao Y. (2016). Manufacturing as the Key Engine of Economic Growth for Middle Income Economies. Asian Development Bank Institute. | Kim J., Park J. (2018) The Role of Total Factor Productivity Growth in Middle-Income Countries. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade. | Kharas H., Indermit S. (2020). Growth Strategies to Avoid the Middle-Income Trap. Duke Global Working Paper Series.

[12] The World Bank Human Capital Index (World Bank, 2020), calculated for Russia, places it in 41st place in the overall ranking of countries. The UN Human Development Index (UN, 2020) for Russia corresponds to the 52nd position in the overall ranking. At the same time, the growth rate of the Russian HDI has recently slowed down sharply, and HCI shows even a slight decline.

[13] World Bank (2020). Russia Economic Report. URL: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/russia/publication/rer

[14] Moretti E. (2013). The New Geography of Jobs. Mariner Books.

*Translated from the original: Liberal Mission Foundation (2021). Stagnation 2.0: consequences, risks and alternatives for the Russian economy. URL: https://liberal.ru/lm-ekspertiza/zastoj-2-posledstviya-riski-i-alternativy-dlya-rossijskoj-ekonomiki-2-n

One comment