_ Pierre Bessard, economist, member of the board of trustees, director, Liberal Institute. Zurich, 2 May 2022.*

Executive summary

The current global recession – which was triggered by epidemiological preventive measures – and the balancing measures for the economy are leading to a new record increase in government spending and debt in many places.

The most extensive empirical studies show a clearly negative relationship between the weight of the state and wealth. This even applies to expenditure that is considered “productive” – for example in the areas of education, research, or infrastructure.

The state has long since exceeded its optimal weight. According to the Rahn curve, depending on the quality of government spending, a share of 15 to 25 percent of gross domestic product should not be exceeded. The optimum is closer to 12 to 13 percent of GDP. A higher proportion weakens the growth potential of the economy.[1]

The costs of government tasks include acquisition, inefficiency, and stagnation costs. In the social sphere, the state has a doubly negative effect in terms of incentives by making work and savings unattractive both through taxes and through social benefits.

A reduction in the tax burden and a refocusing of the state would enable a return to sustainable economic growth. In concrete terms, this could mean reducing taxes on profits and capital – two of the most damaging taxes of all – to zero, the direct one

Abolish federal tax – an anomaly in the system – and strengthen personal responsibility in the areas of old-age and health care.

Bloated government spending

The impact of government weight on wealth is once again a hot topic. This is in view of the looming deep global recession as a result of the preventive containment measures in connection with the Covid-19 epidemic and the balancing measures for the economy (see charts below). Added to this is an ultra-expansionary monetary policy,

which was eased again – possibly to finance part of the public debt – raising fears of inflationary consequences. The additional government spending to “boost” the economy is likely to lead to a further increase in the government’s share of gross domestic product (GDP) and thus to a lasting weakening of the market economy, the free functioning of which is positively correlated with prosperity.

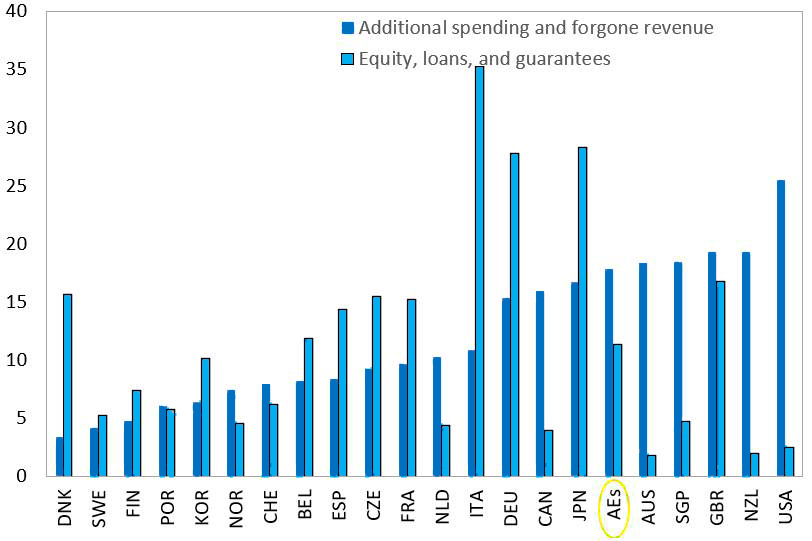

Figure 1: Additional government spending in advanced economies (2020, in percent of GDP)

Source: IMF (2021).[2]

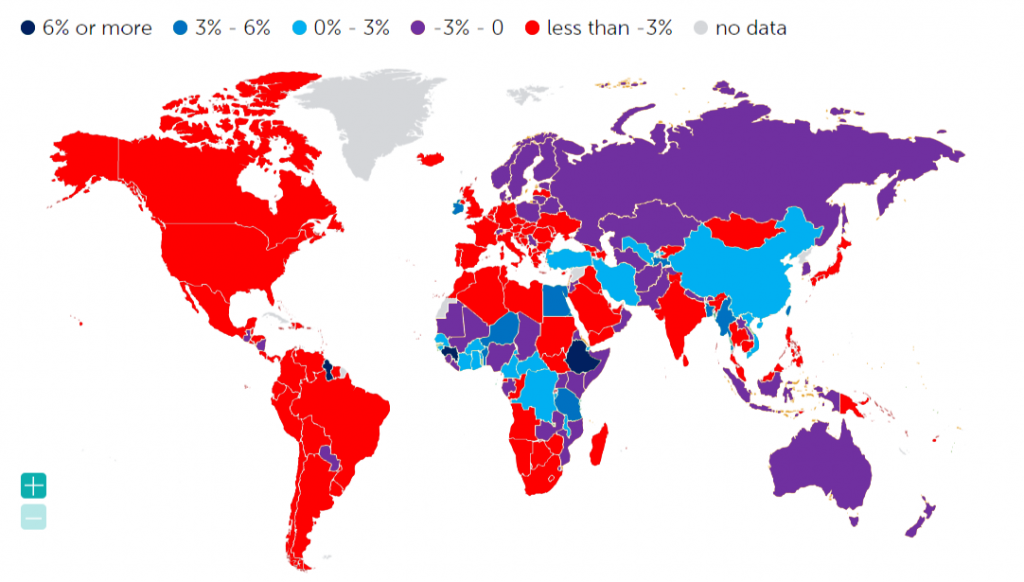

Figure 2: Real GDP growth (2020)

Source: IMF (2022)[3]

Although many economists warn of an increase in the importance of government, there is no a priori agreement on the link between this development and prosperity: economists in the tradition of Keynesianism continue to claim that public spending can stimulate demand and thus boost economic growth.

Even the most critical of economists tend to argue that how spending is used matters more than how much it is spent.

Of course, the qualitative aspect of government spending cannot be ignored: there are important differences between an unproductive increase in bureaucratic staffing or a simple redistribution of income, on the one hand, and carefully designed and debated investments – in infrastructure, for example – on the other. Nevertheless, sustainable economic growth cannot go hand in hand with an excessive state sector: empirical findings on the relationship between state weight and prosperity clearly show this.

Lessons from experience

In the short term, of course, an almost unlimited number of factors can influence the growth of an economy. A country may also experience special conditions related to other policy areas, such as monetary policy or trade liberalizations, which are often difficult to isolate from the scope of the state. For this reason, only the observation of a representative number of countries over a longer period allows relevant conclusions to be drawn.

The connection between the weight of the state and prosperity is thus clearly clarified.[4]

The dominance of the state does not always prevent the economy from growing. But this is growing at a lower level, which, in addition to lower incomes, can lead to higher unemployment or lower life expectancy.[5]

In concrete terms, experience shows that an increase in government size in relation to GDP is reflected in a long-term loss of growth. During the period of state expansion, the negative impact on growth could be even greater. Once the relevant stress has stabilised, the market becomes more resilient, but the economy then grows more slowly: the dominance of the state leads to a systematic weakening of economic efficiency, investment and innovation.[6]

This reality should not lead to the assertion that all state activity is harmful, which would mean that a zero level of the state budget would be the most favourable level for prosperity. But even assuming that the state can play a positive role to some extent – particularly in protecting property rights, administering the judiciary and security production, and in certain infrastructures – it is clear that the impact of state activism quickly translate into a slowdown in economic growth once the functions and size of the state exceed a minimum.

This observation also applies to areas where government spending is seen as ‘productive’, particularly education, research and infrastructure: there is no discernible positive impact on welfare from government spending on R&D and other capital subsidies.[7]

The converse assertion ignores the empirically observed negative effects of the corresponding tax burden. The state merely replaces the private sector by first withdrawing the required revenues from the private sector and then spending them according to a less efficient incentive structure.[8]

For the same reasons, the counterproductive effect of development aid, regional policy, but also planned economy approaches and attempts by the state to actively promote innovation.

It may seem surprising that government involvement in areas such as education, research or infrastructure is not crucial.

But in Switzerland, for example, private companies finance 72 percent of research expenditure.[9]

Ultimately, government spending creates an illusion: the allocation of resources is visible, among other things, in the form of physical construction that everyone can observe. What is not seen are the private sector projects that could not be funded because the funds needed to fund government projects were taxed away from the private sector.[10]

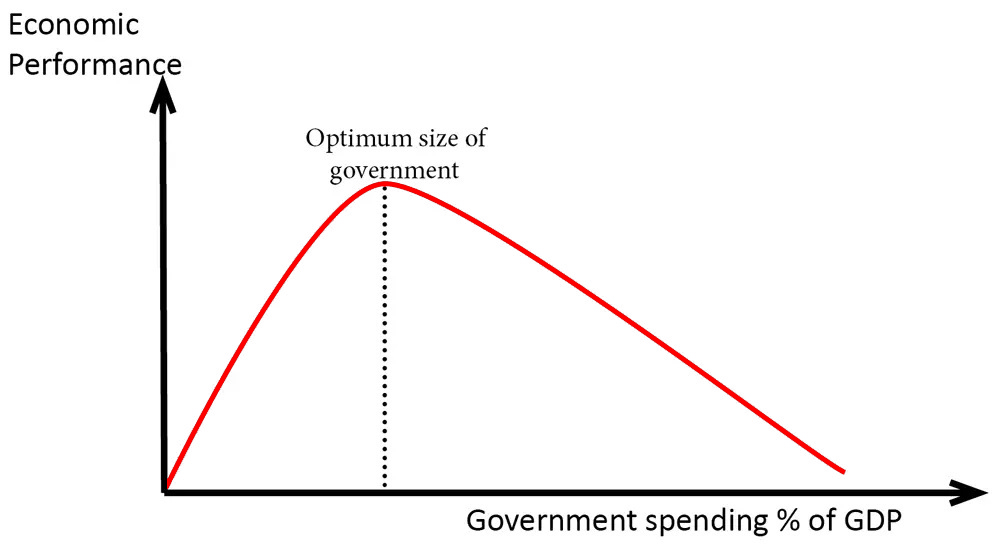

The negative, but non-linear relationship between state size and wealth was formalized in particular by the Rahn curve, named after the American economist Richard Rahn, for determining the “optimal” size of the state.

This optimum lies between a state in which the state is unable to provide basic functions to protect people and property and the legal framework for enforcing contracts and property rights, and a situation in which the state balances economic growth and prosperity with excessive tax burdens and overspending negatively influenced.

On this basis, the weight of the current “typical” state with 30 to 40 percent of GDP (in Switzerland the state ratio is currently 32.9 percent of GDP) proves to be far too high in relation to the goal of optimal economic growth.[11] The public sector should therefore account for 15 to a maximum of 25 percent of GDP – including the central, regional and municipal levels and any social insurance.

However, due to the fact that the state is taking on more and more tasks that should ideally fall to the market economy or civil society, this assessment is being distorted upwards. The “optimal” ratio is more likely to be 12 to 13 percent of GDP, as the following figure shows.

Figure 3: The Rahn curve

Source: Liberal Institute (2022).

The cost of government spending

Practical experience clearly shows a negative correlation between a state size that grows beyond this optimum and prosperity. But experience only illustrates this relationship, it does not yet explain it. The explanation of this causality is all the more important because, despite its empirical evidence, it is regularly questioned. Therefore, it is important to analyse the costs of state activism.

The first cost, of course, is the appropriation of resources: any government spending requires a source of funding that is withdrawn from the private sector. This means that the private sector no longer has access to the same amount of funds. In any case, in the short or longer term, the same amount of capital will no longer be available for private investment. Through this process of

Appropriation does not create additional wealth.

Typically, more than 90 percent of government funding comes from taxes. But the acquisition costs also include the national debt, which requires a corresponding tax burden in the future.

In addition to the official debt, there is also implicit debt in the form of unfunded pension promises from the pension system.

Added to these costs is the implicit inflation tax that arises from the government’s money monopoly. The currently low consumer price inflation should not hide the fact that the price pressure on asset markets such as stocks and real estate is dissipating, causing bubbles to form and potential crises there.

Finally, regulations can also be viewed as a form of taxation: instead of directly intervening, the state directs the allocation of funds by restricting their use or specifying a specific use.

At first glance, the public sector seems capable of delivering an impressive amount of services thanks to the resources taken from the private sector. But government spending is not like market-based services: without price signals and profit measurement, government production is like groping in the dark. In the absence of information about consumer preferences – communicated through prices – it is impossible for the state to know what to produce, how and in what quantity. Without a focus on profit, without the discipline of competition and without responsibility for losses and failures, spending will never slow down.

Rather, they depend on bureaucratic incentives. Spending targets even encourage officials in charge to use up allocated budgets. Far from stimulating demand or boosting economic growth, the government is exerting a negative multiplier effect.[12]

In addition to these appropriation and inefficiency costs, any public spending creates saturation and crowding-out effects by replacing private offerings. Since the state finances its expenses through coercion or protects its areas of activity through special legal rights, private companies are exposed to unfair competition.

In addition, government intervention hinders the innovation process: private sector entrepreneurs are constantly looking for new options and opportunities; government programs, on the other hand, are often inflexible, bureaucratic, and set by laws that cannot be changed without finding new democratic majorities.

It is true that some government spending on education or infrastructure – unless done with the most obvious inefficiency – has the potential to contribute to people’s productive capacities. But even in this case, these expenses cannot be considered productive, since they are financed by taxes:

As we have seen, there is no empirically proven relationship between the level of this spending and wealth when fiscal costs are taken into account.[13]

Government regulations obscure the fact that free market and civil society actors – both for-profit and not-for-profit – have the ability to meet investment needs in areas such as education and infrastructure.

Of course, the state, through its financing method, is able to produce such goods in excess, but with the consequence of a decline in prosperity due to the inefficient use of scarce resources.

In the social sphere, government spending also causes behavioural distortions. Taking resources from the private sector reduces incentives to work and invest: the higher and more progressive government taxes are, the disproportionately negative impact they have on production. In this way, the state subsidizes underutilization and misallocation of resources, making leisure and consumer spending artificially more attractive compared to the productive activity and savings on which wealth-enhancing capital formation depends.

The “social” activity of the state has a doubly counterproductive effect. First, government programs have a dampening effect on capital formation due to taxation.

Second, they snatch personal responsibility away from the individual by subjecting all citizens to uniform programs – be it in old-age provision, in the health system or in the area of education. Saving is not only becoming more difficult because of taxation but is also seen as less necessary because of the apparent substitution by state provision.

Government spending thus discourages actions that would be significantly more profitable for those affected, such as capitalizing on their retirement savings or setting up personal health or education savings accounts.

At the same time, such solutions would reduce the costly incentives to overuse government services created by the concession and collectivization of spending. For these reasons, social policy is also characterized as a “war of one against the other”[14].

Unlike private insurance and savings products, or voluntary transfers inspired by altruism, social benefits, often introduced with good intentions, create perverse incentives that create a constant source of social tension and reduce wealth.

How can the economy be revived?

The impact of excessive government on wealth shows how flawed the notion of government indispensability is in most sectors of the economy and that increased public spending is a mistake.

This raises the question of how the welfare of society can be promoted in a crisis situation.

The answer is exactly the opposite of more government spending, namely a refocusing of the state on its essential core tasks and a parallel reduction in its burden on the private sector.

The lockdown has highlighted the role of productive work, trade and savings in prosperity: the sustainable well-being of society has no other source. This requires the provision of goods and services that meet consumer expectations through doing business in the markets.

This value creation must therefore be facilitated by being less heavily taxed. In the best case, by first reducing taxes on profits and capital to zero: this taxation only contributes to public sector bloat, since the burden falls indirectly on the citizens anyway, be they employees, customers, suppliers and – to a lesser extent – the company’s shareholders. Corporate taxation is by far the most detrimental to employment and wages, as it directly taxes productive capital that should be reinvested in corporate activities and product or process innovation.[15]

The second measure to consider is the abolition of the federal direct tax, which has been due for more than 70 years. This anomaly in the Swiss tax system – originally introduced as a makeshift measure to cope with the defense efforts during the world wars – contributes disproportionately to the problematic development of central government.

By waiving this tax, the federal government could finally focus on its few legitimate responsibilities and redefine the scope of its overwhelming administration.

Such an investment in the future in the form of tax breaks would be by far the wisest investment that could be made: it would return resources to the private sector on the basis of individual decisions and corporate economic calculations, thereby reducing wastage in political and bureaucratic spending.

At the same time, the AHV reference age could be raised to 70 and then gradually to 75 in order to increase personal responsibility for old-age provision and reduce unnecessary subsidies.[16]

Over the course of seven decades, average life expectancy has risen from 67 to 83 years, while the arduousness and risks of work continue to decrease and health improves in a service- and knowledge-based society. Such a long post-work retirement period can only be explained by the institutional immobility and inability to reform of a poorly designed redistribution system.

The restructuring of the AHV as a real old-age insurance to supplement private income and assets would be a beneficial reform in several respects: It would not only reduce costs, but also strengthen the economy by avoiding the early retirement of qualified and experienced workers.

Finally, health insurance should focus on large risks in order to reduce costs. Excessive collectivization of healthcare spending is recognized as the main cause of the explosion in health insurance premiums. Unnecessary acts of over-medicalization resulting from current perverse incentives are estimated to account for up to a third of spending.[17]

To enable the development of more cost-effective solutions, health insurance should focus on serious and chronic diseases, which would also promote greater awareness of risky behavior and prevention.

Current health care expenditures could be funded through individual health savings accounts that would be fully tax-exempt and remain the property of their holders.

The most serious misconception about “stimulus policies” to stimulate the economy is the belief that there is no alternative to the state.

The free market and civil society, that is, the people who are directly affected by their decisions, can not only produce the goods and services necessary for their well-being, but experience has shown that they do this better and more cheaply.

Even if there is no “perfect” panacea for a complex and multifaceted situation, the current exceptional crisis requires first and foremost the release of productive energies and resources for recovery – above all in the interests of younger generations and their perspectives, which are the dominance of the taxing and redistributing state would be most disadvantaged.

Notes

[1] From personal communication with Richard Rahn on 17 May 2017.

[2] IMF (2021). Fiscal Monitor Database of Country Fiscal Measures in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. URL: https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Fiscal-Policies-Database-in-Response-to-COVID-19

[3] IMF (2022). World Economic Outlook (April 2022). URL: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/datasets/WEO

[4] See Lorraine, Mullaly, analysing 30 OECD countries over a 45-year period, cited in Bessard P. (2017). Individual Rights and Tax Oppression in the OECD. Liberal Institute.

[5] This is reflected in the annual Fraser Index of Economic Freedom co-edited by the Liberal Institute. awewe

[6] This is the conclusion reached by Gwartney J. et al. (1998), who aanalysed 23 OECD countries over the period 1960-1996 and 60 countries, including less developed countries, over the period 1980-1995. See Gwartney J. et al. (1998). The Size and Functions of Government and Economic Growth. Joint Economic Committee.

Economists at the OECD come to similar conclusions, noting that the weight of government, as measured by the tax burden or government spending, “both directly and indirectly” has a negative impact on private capital accumulation. See: Bassanini A., Scarpetta S. (2001). The Driving Forces of Economic Growth: Panel Data Evidence for the OECD Countries. OECD Economic Studies. No. 33. OECD.

[7] Minford P., Wang J. (2005) tested two growth models, an activist and an incentive, over the period 1970-2000 to arrive at this conclusion. See: Minford P., Wang J. (2005). Public Spending and Growth- Studies on Debt and Growth. Institute for Research in Economic and Fiscal Issues.

[8] Minford P., Wang J. (2005). The authors cite 24 representative empirical studies that show the negative effects of the tax burden on economic growth.

[9] Federal Statistical Office of Switzerland (2017).

[10] See on this subject: Frédéric Bastiat F. (1863). «Ce qu’on voit et ce qu’on ne voit pas. Oeuvres complètes de Frédéric Bastiat. Volume 5. Paris.

[11] Eidgenössische Finanzverwaltung der Schweiz (2020).

[12] Mitchell D. J. (2005). The Impact of Government Spending on Economic Growth. Backgrounder 1831. Heritage Foundation.

[13] Mitchell D. J. (2005).

[14] Salin P. (2000). Liberalisme. Paris.

[15] See also: Bessard P. (2008). The Illusion of Corporate Taxation. Liberal Institute.

[16] See also: Bessard P., Pamini P. (2016). Beyond the Three Pillar Myth. Liberal Institute.

[17] See also: Bessard P., Kessler O. (2019). Too expensive! Why we pay too much for our health care. Liberal Institute.

*Translated into English from the original with the kind permission of the author: Bessard P. (2020). Zu viel Staat bedeutet weniger Wohlstand. Liberales Institut. URL: https://www.libinst.ch/publikationen/LI-Briefing-Bessard-Rahn-Kurve.pdf