_ Norbert Kleinwächter, member of the German Bundestag. Berlin, 2018.

Introduction

“The pension is safe.” This sentence, which Norbert Blüm had posters posted all over Germany in 1986 and which he repeated many times in plenary debates, was to become one of the biggest half-truths in politics. In 1986 the pension was indeed relatively secure. Even in 1997, when the CDU pension reform was being debated in the Bundestag, the pension could just about have been made future-proof with suitable policies.[1] However, despite repeated warnings from the Federal Constitutional Court, those in government failed to make the appropriate adjustments in politics and society

In Chapter 2.1, the present study illustrates the problem of lowering the pension level to secure income in old age and discusses the weaknesses of the three-pillar model of pension provision consisting of statutory pension, company pension scheme and funded savings plans. Chapter 2.2 examines the causes of the German pension crisis, which are due to a design flaw in the statutory pension insurance system. Since all employees subject to social security contributions will later participate in the pension system, but in old age only a few people will be employed due to far too low birth rates, the majority of pensioners will no longer be able to be adequately cared for from 2025, even with the best productivity. At the same time, the system of statutory pension insurance contributes to childlessness through false incentives and by advantaging childless people, thus exacerbating its own crisis.

After discussing the political options for action, a concept is presented that makes the system of statutory, pay-as-you-go pensions fair, future-proof and also performance-based for those who have made the full contributions to it. The core of the concept is the design of the statutory pension as a three-generation contract with systematic consideration of the generative component: Anyone who has children and has therefore invested in the contributors of tomorrow should receive more redistribution pensions than those who hasn’t made this generative contribution to the pay-as-you-go system, which is utterly dependant on it. This eliminates the demonstrable effect that the current structure of pension insurance favors childlessness. Rather, the expenses of bringing up children and their contribution to securing the pay-as-you-go pension system are taken into account by a child factor in the pension formula. The statutory, pay-as-you-go pension, which in the so-called “three-pillar model” represents only one type of income alongside company pension schemes and funded pension schemes, remains a central type of income in old age for those who were less able to make private provisions due to their child-rearing efforts, while for the childless – private provision increasingly comes to the fore. This must also be reconsidered and improved in times of low interest rates.

The present concept therefore envisages ending the preference for certain Riester products through subsidies and instead promoting self-determined wealth accumulation. By setting up public pension funds as optional supplementary insurance, funded provision is to be simplified and made accessible to the general public. By making retirement more flexible, the pension should also better recognize people’s individual employment biographies.

For reasons of economy and fairness, it is also planned to include civil servants and the self-employed in the statutory pension system. This stabilizes the pension level in the medium term, dampens the increase in contributions and means that all workers in the country, whether they are employees, civil servants or the self-employed, participate in similar benefits in old age.

This concept is based on analyses by leading economists. Representatives include Hans-Werner Sinn, Martin Werding and Susanne Kochskamper, whose ideas also shape the present concept. The present study also fulfils the central ideas of the German Bishops’ Conference on family-friendly pensions.

At this point it should be expressly emphasized that these ideas are not a “mother’s pension” and also not a program to support children. This concept distances itself from election campaign promises and unsustainable social benefits. The author is very clear in favour of extensive support for children and families. However, the subject of this concept is not family support, but compensation for the generative contribution that parents make, and which is necessary for the existence of the statutory pension insurance.

The reform proposed here does not “punish” childless people either. Rather, the planned changes within the statutory pension balance out disadvantages that families have been demonstrably incurring for decades and that should have been corrected a long time ago. In a purely economic sense, the reform outlined here takes into account the generative contribution that parents make to the existence of the pension system.[2] It is time for politicians to finally react. A policy that creates incentives for childlessness, in particular by exposing families to an increased risk of poverty and cheating childless people in their pensions, must be changed today rather than tomorrow in the interest of the future of our social systems. Renown economist Hans-Werner Sinn also warns against shying away from family-friendly policies for historical reasons:

“It is not politically correct to lament [the birth deficit] in a country that has had negative experiences with government population policies. But it is necessary, because political correctness, borne by the waves of mere illusions and social ideologies, will one day crash on the cliffs of economic reality anyway. […]

The state must also change course because it is the state that has made a significant contribution to changing the social value of the family and to the childlessness of Germans through its social security systems, which have separated the fate of the individual from the consequences of his or her fertility decisions.”[3]

Retirement – We can’t do it that way

2.1. The statutory pension insurance (GRV) as an expensive poverty pension

Politics in Germany has failed across the board when it comes to pensions. The pay-as-you-go pension is in its very last relatively fat years, which will come to an end as the so-called “baby boomers” enter retirement. Between 2025 and 2030, the contribution rate will inevitably skyrocket, while pension levels will continue to fall.

Poverty in old age will increase drastically, above all if private provision during working life could not be financed or is ineffective.

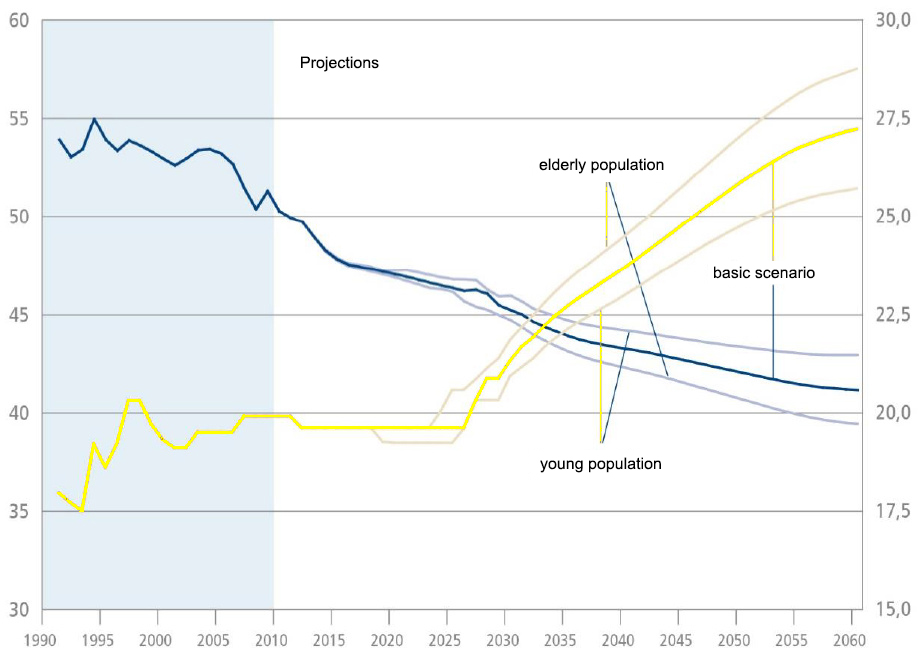

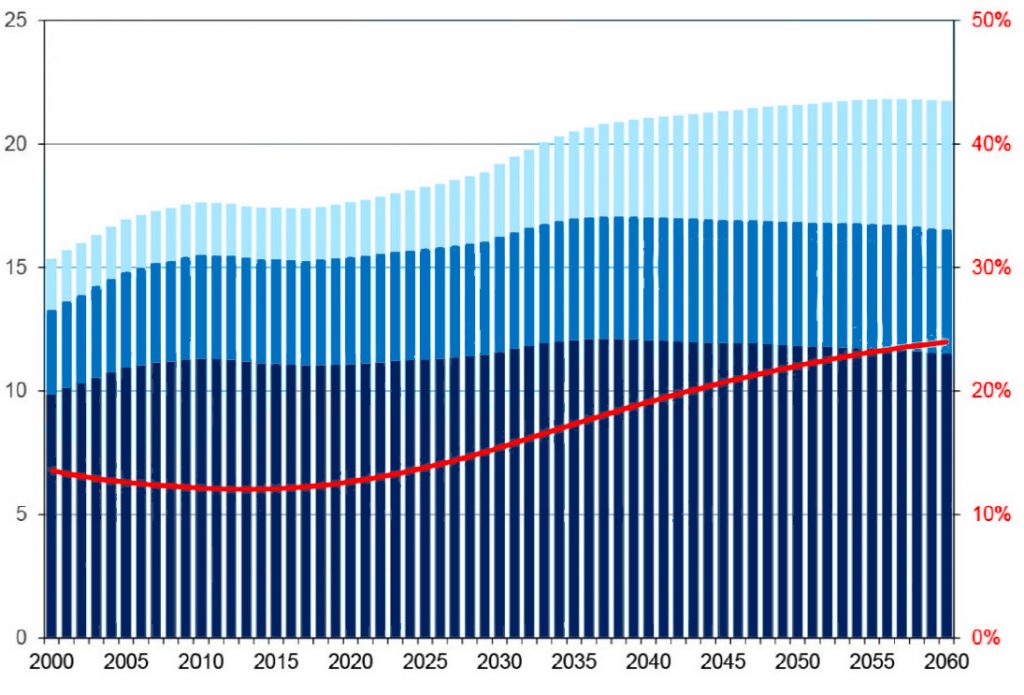

By 2030, the contribution rate to the statutory pension insurance is to increase from 18.6 percent to 21.6 percent. That’s an increase of 16 percent. The pension level is expected to fall by 6.6 percent from an already meager 48.2 percent to 45.0 percent.[4] By 2060, the conditions of statutory pension insurance will continue to deteriorate if the current pension policy is retained: in 2060, a contribution rate of 27.2 percent and a net pension level of 41.2 percent before tax is expected. The contribution rate can be as high as 28.7 percent and only allow for a pension level of 39.5 percent if a more pessimistic scenario occurs and the population is older than expected. This can be the case, for example, with a lower birth rate, higher life expectancy or lower immigration than assumed.[5]

Figure 1. Development of the pension level and the contribution rate in Germany (1990 – 2060, in percent)

Net standard pension level (before taxes) (left axis, blue), contribution rate of the statutory pension insurance (right axis, yellow) | Source: Werding (2013).

However, a pension level of 48.2 percent does not mean that a pensioner will also receive 48.2 percent of their last earnings as a pension. The pension level describes the ratio of a pension to the current average wage for a “basic pensioner”. The corner pensioner is a fictitious pension recipient who has worked for 45 years and has always earned exactly the average gross income of currently 37,873 euros per year.[6] This does not reflect the reality of the pension. In fact, the insured pensions are significantly lower because they are calculated, in addition to a number of other factors, primarily from the number of earnings points and the contribution years. An employee receives a full payment point per year if he has earned average gross earnings in that year. In the current year 2018, an employee receives 1.00 payment points with an income of 37,873 euros, but with an annual salary of 20,000 euros, for example, only 0.53 payment points. When you retire, the earnings points you receive each year are added up. The following table shows how many contribution years are based on today’s insured pensions and how many earnings points have been earned on average per year.

Figure 2. Insured pensions in the statutory pension insurance system

| Subject of the verification | Germany in total | West Germany | East Germany |

| Men | |||

| Number of pensions | 6,467,605 | 4,950,648 | 1,516,957 |

| Earning points per year | 1.0176 | 1.0250 | 0.9934 |

| Number of years | 41.42 | 40.47 | 44.51 |

| Pension payment amount in euros | 1,127.10 | 1,130.65 | 1,115.51 |

| Women | |||

| Number of pensions | 7,468,072 | 5,902,654 | 1,565,418 |

| Earning points per year | 0.7519 | 0.7348 | 0.8165 |

| Number of years | 30.37 | 27.55 | 41.01 |

| Pension payment amount in euros | 673.06 | 617.55 | 882.37 |

Source: Bundesregierung (2017).

Even today, pensioners do not meet the demands of a “basic pensioner”. While women are very far away from basic pensioners with around ¾ of the earnings points per year and only 2/3, only very few men achieve an actual pension level of 48.2 percent. On average, men receive 1,127.10 euros and women 673.06 euros per month before taxes from the statutory pension. The average pensioner of today therefore receives 883.78 euros per month and is thus only 18 percent above the subsistence level for a single person, which is 9,000 euros per year.[7]

These amounts mean that the pension insurance no longer fulfills its task of stabilizing income in old age. For people who had no opportunity to make private provisions, i.e., who have no company pensions or profitable assets, today’s values already mean a safe descent into old age poverty. The pension level will continue to fall and the sustainability factor in the pension formula10 will ensure that there will be hardly any pension increases.[8] Single people and families with below-average incomes are particularly at risk of poverty. The effect of the lowering of the pension level hits the East Germans with full force, as they draw their retirement income primarily from the pay-as-you-go pension.

Figure 3. Shares of income components in gross income volume (in percent)

| Area / group | Statutory pension insurance | Other old age insurance benefits | Private provision | Transfer payments | Other income |

| Germany | |||||

| All persons | 63 | 22 | 8 | 1 | 7 |

| Married couples | 56 | 22 | 8 | 0 | 13 |

| Single men | 60 | 22 | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| Single women | 71 | 17 | 6 | 1 | 4 |

| West Germany | |||||

| All persons | 58 | 25 | 9 | 1 | 8 |

| Married couples | 50 | 26 | 10 | 0 | 13 |

| Single men | 55 | 25 | 9 | 1 | 9 |

| Single women | 67 | 20 | 7 | 1 | 5 |

| East Germany | |||||

| All persons | 90 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| Married couples | 81 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 12 |

| Single men | 89 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| Single women | 94 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

Source: Bundesregierung (2017).

For the year 2029, the Scientific Advisory Board of the Federal Ministry of Finance forecasts an increase in the old-age poverty rate from 3.0 percent in 2014 to up to 5.4 percent, although this can only be sustained if the pension reforms are not softened by campaign gifts, thereby jeopardizing the pension level.[9] The financial consequences of projects such as the mother’s pension and the pension at age 63 have been mitigated by a good economy, positive figures on the labor market and an intermediate demographic high, but are jeopardizing the further development of pension levels.[10]

In addition, the relatively low old-age poverty rate reflects the fact that the labor market of the 20th century made corresponding contribution payments possible. However, the level of individual pension entitlements will decrease as a result of the changes that the labor market has undergone:

“Increase in mass and long-term unemployment; increase in (solo) self-employment and change between different forms of employment; interrupted employment biographies; growing low-wage sector, expansion of atypical and contributory employment. These developments […] influence the individual pension entitlements achieved during working life. Those who have been unemployed for a long time or only earn very little pay correspondingly low pension contributions and acquire low entitlements. The same applies to employees who work part-time, especially those who work marginally.”[11]

Another economic crisis can also have negative effects at any time.

Since the Riester/Rürup reforms, politicians have been promoting provision in so-called Riester contracts as a way out of the poverty trap in old age, but these are also not sustainable for poorer people and a large number of employees:

“The number of Riester and Rürup contracts concluded is considerable, the accumulated assets less so. It is to be feared that people with an above-average income in particular will take advantage of the opportunity to accumulate wealth tax-free, but that those affected by poverty in old age will make insufficient or no provision at all.

In the area of company pension schemes (bAV) things are hardly looking any better. Public employees are covered across the board. In the private sector, however, it is mainly employees of large and medium-sized companies who have entitlements to company pensions […] Things are less good for small and medium-sized companies and their employees. If at all, company pension schemes are only practiced here in the form of insurance-based solutions […] This usually implies higher costs […] If working hours are reduced, if there is a longer exemption from contributions due to unemployment, illness or child-rearing periods, there is a risk of financial loss for the employee. […]

In total, around 50 percent of private-sector employees have some kind of entitlement to a benefit from the company pension scheme. However, it is doubtful whether these entitlements are sufficient in all cases, especially in the case of low earners, to close the pension gap.”[12]

If the statutory pension is not reformed, in the old population scenario mentioned above in 2060, a contribution rate of 28.7 percent would only result in a pension level of 39.5 percent. The compulsory levy of more than a quarter of income from work would therefore not even grant the average pensioner a pension at the subsistence level according to the current composition. The pay-as-you-go pension is dead in its current form.

The company pension scheme and the Riester savings contracts cannot compensate for the losses of a lower pension level. Since groups at risk of poverty (above all the unemployed, single parents, the low-skilled or foreigners)1 and households with low or uncertain incomes are not able to save enough, they are particularly at risk of poverty in old age.[13]

The savings and provision expenses that become necessary for employees in addition to paying into the statutory pension reduce consumption and thus dampen economic growth and wage increases.

In addition, investing in the capital market is often not worthwhile because it sometimes generates low returns and is also exposed to the risks of the capital market.

The funded systems often perform poorly and are unable to keep their promises of returns.[14]

A look at the Riester savings contracts with guarantees, which are heavily subsidized by the state, shows this clearly: three quarters of these products only achieve unacceptable returns of between 0 and 2 percent. The mean maturity benefit (median) is only just above the contributions paid in.[15] The Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, unperturbed by this, calculates in the pension insurance report 45 years of contributions and an interest rate of between 2.5 percent and 4.0 percent and thus comes up with a steady Riester retirement provision contribution of 4 percent to the pension level including the Riester pension of approx. 52 percent before taxes.[16]

Interrupted careers, which in turn make constant savings more difficult, are not taken into account. Cases of reduced earning capacity and pensions for surviving dependents are also usually only covered by the first pillar, but not by company or funded old-age provision.[17] Hardly any pensioner will achieve a pension level of 50 percent before taxes with the statutory pension and these Riester products.

Pension provision, which the CDU, FDP, SPD and Greens have reformed into this downward spiral, inevitably leads to the poverty crisis in old age due to gross conceptual flaws. The German pension system is based on three unreliable pillars and does not form a solid basis for old-age security. The statutory redistributive pension pays average pensions close to the subsistence level with increasing pension contribution rates with an ever-lower pension level.

Company pension models, for which households at risk of poverty cannot save, and Riester savings contracts, which are neither crisis-proof nor have acceptable returns, are intended to make up for these deficits. Such a system is not a solid basis for old age security. If people rely on it, they are abandoned.

In view of these blatant abuses, the changes negotiated by the grand coalition in August 2018 are just euphonious campaign gifts. Limits for the contribution rate (max. 20 percent) and pension level (at least 48 percent) by 2025 and half a payment point extra for children born before 1992 do not change anything about the pension crisis that will start from 2025 and only slightly improve the systematic disadvantage of parents in the pension system.[18] A fundamental reform of the statutory redistribution pension as well as the operational and funded second and third pillars are necessary. Germany needs a new, functioning pension system.

2.2. Causes of the pension crisis

To put it succinctly, the pension crisis is rooted in the way governments have shaped federal policy. Pension gifts were often given during election campaigns, and the statutory pension insurance itself was a huge election campaign gift. In 1957 the CDU and Chancellor Konrad Adenauer had to win the election to the 3rd German Bundestag. Driven by the opposition, which was able to score points in some policy areas, the situation of pensioners should be improved. These had only meager pension income after the funded pension system that Otto von Bismarck had introduced in 1889 was no longer efficient. Before Bismarck, there had only been provision by one’s own children in the family. The introduction of the pension in 1889 did not aim to create a full pension but was intended to serve as an additional pension and emergency security. After the hyperinflation of 1923 and the end of the Reichsmark after the Second World War, the capital stock of the pension insurance was so weak that the pension level was only around 20 percent despite extensive tax support. The situation of pensioners urgently needed to be improved.

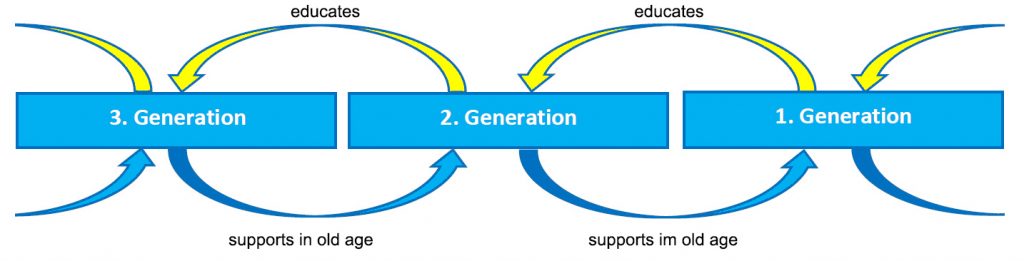

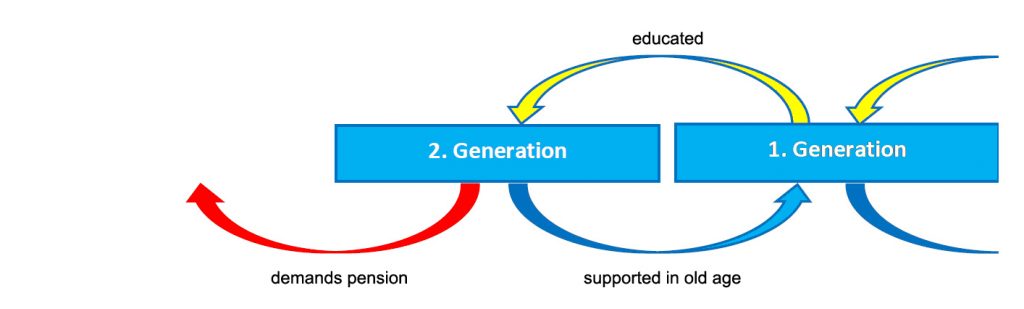

Adenauer resorted to a system that Wilfried Schreiber had developed for the Association of Catholic Entrepreneurs. The idea went away from the crisis-prone, funded system to the pay-as-you-go system, which is based in principle on the old idea of the extended family: in an extended family, the employed take care of both the children and the elderly. In return, they can rest assured that their own children would also take care of them.

Schreiber raised the idea of the extended family to the level of society as a whole. In order to cushion the individual risks of the individual, society as a whole should take the place of the extended family. The pay-as-you-go system still works like in an extended family: the employed perform a double service by behaving the parents’ generation on the one hand and raising the children on the other, who in turn will later pay their pensions.[19]

Figure 4. The traditional pay-as-you-go pension as a generational contract

Source: MIWI Institute.

The allocation amount is always used up immediately. What the working people pay in is paid out directly to the pensioners; with the exception of a fluctuation reserve, nothing is saved. This is still the case today: The 277.738 billion euros that the pension insurance received in 2016 from contributions (215.422 billion euros) and the federal subsidy (69.709 billion euros) went in the form of expenditure of exactly the same amount ( EUR 277.738 billion) for pensions (EUR 259.354 billion) and health insurance for pensioners (EUR 18.393 billion) to the current generation of pensioners.[20] However, the payments also include benefits for mothers’ pensions, for example, which are actually to be assessed as unrelated to insurance.

The immediate payment of the amounts also means that nobody who is employed saves for old age in the statutory pension insurance. The contributions are not a reserve for old age but serve exclusively to provide for the current generation of pensioners. So, the money is completely used up. In return, there are earnings points that are later intended to ensure that when the contributions are distributed, everyone resumes the position they held in their working life: the earnings points reflect the individual relationship to average earnings and are ultimately used to calculate the pension in comparison to the other pensions. This is not a problem as long as the contribution cake is growing.

Economics Minister Ludwig Erhard, Finance Minister Fritz Schäffer, economists and demographers all stormed against Adenauer’s pension plans in 1957. They pointed out that the pension system relies on constantly rising wages and balanced demographics. Even then, despite a fertility rate of 2.3 children per woman, it was foreseeable that the age tree would grow upwards. In addition to the pay-as-you-go pension, Schreiber himself had also called for a child and youth pension in order to guarantee contribution-based support not only in old age, but also during child-rearing, thus guaranteeing the future of a pay-as-you-go pension model. A three-generation contract was essential for him, because the children would secure his pension in the future. Adenauer brushed aside these concerns with the famous sentence: “People always have children.”[21]

That was before the pill break. Many of the numerous baby boomers decided not to have children and participated fully in the economic miracle. The virtually non-existent family policy also gave no reason to decide to have children. The pay-as-you-go pension insurance, in which only income from work is taken into account, decoupled old-age security from whether you have children yourself, and made security possible in old age even without them. It individualized the effort involved in raising children and socialized the rewards.[22] It even made it possible to make a better living in old age when one could concentrate fully on gainful employment instead of on children. Furthermore, there was no question of effective support for families. Families inevitably had a significantly lower standard of living than childless ones. Childlessness thus became the new winning model, and the extended family gave way to the small family with 1 or 2 children.

“Being childless used to be a threat to one’s own life that had to be avoided at all costs. Today, being childless gives rise to a massive material advantage that more and more people are claiming for themselves. The new Golf and the holiday in the Maldives can be financed with the money that was saved by raising children or that the woman was able to earn because she decided to work instead of having children. Especially the lower middle class of society, which used to have high birth rates, has discovered a way to achieve material advancement in childlessness. While the threat of childlessness is as present today as it was then, it has spread diffusely throughout the community. Germany is aging, the country’s dynamism is slacking, the welfare state is falling into crisis, and yet the individual hardly benefits if they make their contribution to preventing this development.”[23]

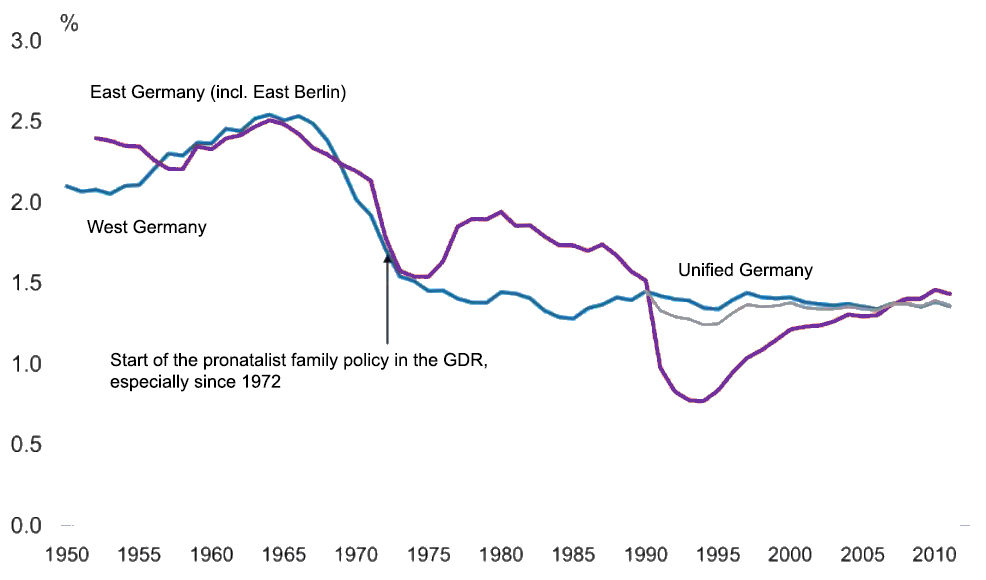

Family policy and economic decisions do affect fertility, and these decisions were anything but positive for expectant parents in West Germany. The inadequate conditions for families in West Germany became particularly clear with the accession of two regions: Saarland joined Germany in 1957, with the result that the birth rate fell from the relatively high French level to below the overall German level within a very short time. The situation was similar after reunification. Here the fertility curve in eastern Germany fell significantly. On the other hand, the pro-natalist family policy in the GDR from 1972 led to a significant increase in births (Figure. 5.).

Figure 5. Fertility rates in Germany (1950 – 2010 in children per woman)

Source: Federal Statistics Burau (2012).

However, today’s pension policy in Germany must be seen as a massive intervention in the family planning of young couples. Because pension insurance socializes almost all of the income from bringing up children, meaning that there is no economic benefit left for the parents, it influences decisions to the detriment of children.

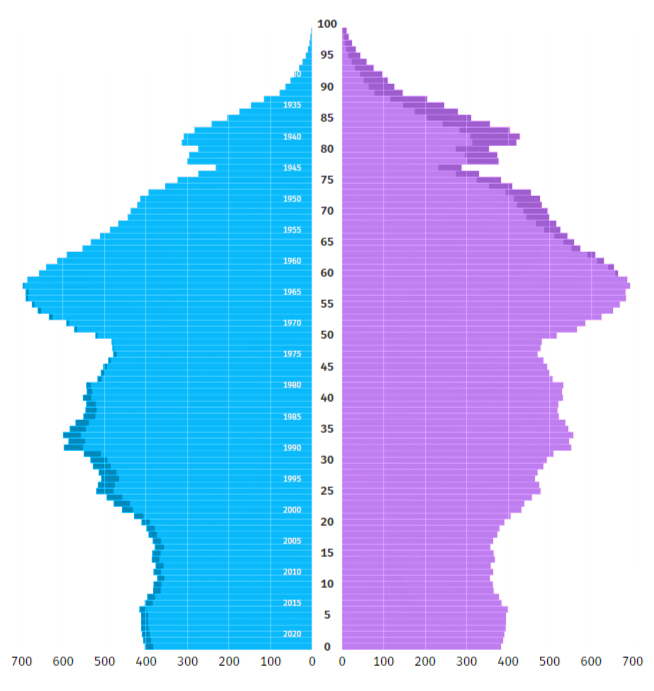

In the age pyramid, the result of the childlessness policy today is as follows (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Age structure of the German population (1950 – 2022)

Men (blue, left side); women (right side, purple). | Source: German Federal Burau of Statistics (2022).

Adenauer’s two-generation contract was ultimately terminated: poor family policies, a short-sighted, pay-as-you-go pension system, the pill, and a general change in values and attitudes ensured that there were hardly any children after the baby boomers. Fertility fell to 1.3 to 1.5 children per woman.

Between 2025 and 2030, baby boomers will retire and retire. They are the largest cohort in terms of numbers, have a higher so-called probability of survival until retirement and a higher life expectancy after retirement. In 2002, 90.2 percent of women and 81.3 percent of men lived to retire. Life expectancy in that year was 19.5 years for women and 15.8 years for men. In 2010/12 it was 20.7 years and 17.5 years respectively. In 2030 it will be 22.6 or 18.4 years, in 2060 it is expected to be 25 or 22 years.[24] The old-age dependency ratio is increasing (Figure 7).

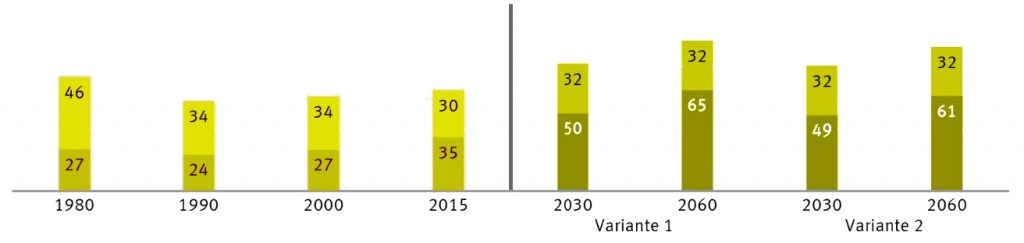

Figure 7. Development of the youth and old age quotient

Youth quotient (dark yellow), old age quotient (light yellow). | Source: Bundesregierung (2017).

The old-age dependency ratio indicates the number of people over the age of 65 for every 100 people between the ages of 20 and 65. In 2030 there will be 32 young people and 50 old people for every 100 people between the ages of 20 and 65. In 2060 there will be 32 young people and 65 seniors. In 2030, six people of working age will support 2 children and young people and 3 pensioners. The problem of the so-called “sandwich generation”, at the same time raising children, support pensioners, must make provisions for old age and also have to feed themselves, will intensify.

In 2017, most families only had one or two children. Three children are already the exception.[25] Among the women born between 1949 and 1963, i.e., those who will retire in 2030, 15.8 percent are childless.[26] No other developed country on earth than Germany has so few newborns in relation to its population size, even though 23 percent of new-borns have at least one parent from abroad.

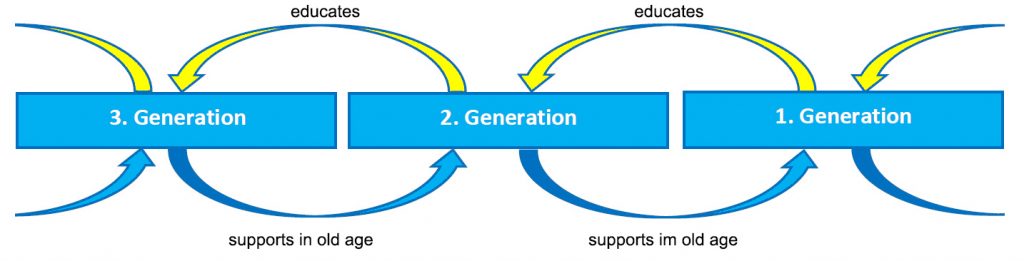

For many future pensioners, the generational progression looks simplified as follows (Figure 8).

Figure 8. The traditional pay-as-you-go pension under an insufficient fertility rate

Source: MIWI Institute.

The problem is simple, yet serious: after a long, hard-working career, retirees are asking for their “earned pension,” but the pension system is finding it increasingly difficult to pay out those claims because of the lack of contributors. Immigration cannot solve this dilemma either, because only well-qualified immigration would actually contribute to an improvement in the pension situation. For this to happen, the qualification level of immigrants to Germany would have to rise significantly, which is not foreseeable.[27] In fact, immigrants burden society financially with a net fiscal burden of 2,300 euros per immigrant per year in the first ten years.[28]

There is an open discussion in the literature as to whether childless people should be entitled to a pension in the statutory pension insurance system at all:

“If fewer children are born, the contributions to the pension fund have to increase or the pension payments per pensioner have to decrease so that people without children can also be cared for. The inclusion of childless persons is problematic. In the pay-as-you-go system, insured persons with and without children should not be promised the same level of old-age pensions as the statutory pension insurance does, even if the contributions are the same. At least not without bringing the funds saved for raising children – be it voluntarily or involuntarily – into the insurance as a supplementary capital stock. In the statutory pension insurance, some of the insured are tacitly relieved of the responsibility for old-age provision, regardless of a means test. Against the background of a growing number of childless [sic!] co-insured persons, the lack of incentives to make their own old-age provisions are now becoming increasingly problematic.”[29]

A reestablishment of the equivalence of provision and consideration is therefore required. Since one’s own contribution payments only served to support the older generation, the actual pension benefit consists of having children, raising them well and educating them well.[30] Thus, the equation is not

contribution payment → pension,

but:

contribution benefit + parenting benefit → pension.

A generation-fair pension system must take this into account.

2.3. Political alternatives for action

Due to the increasing number of pension recipients with claims to the statutory pension insurance, the challenge is to balance revenue and expenditure. Revenue must increase or expenditure decrease, or both. Bad coverage would always have to be compensated with a tax subsidy, which is a burden on the younger generation.

The pension policy of the past 20 years aimed primarily at reducing expenditure. The formula for calculating the current pension value includes the Riester factor and the sustainability factor, which in the long term reduce the level of entitlement.

Figure 9. The calculation of the current pension value in Germany

aRW = aRWt-1 * BEt-1/BEt-2 * 100-4-RVBt-1/100-4-RVBt-2 *[(1-RQt-1/RQt-2*a)+1]

Source: IW Cologne.[31]

At the same time, the “pension at 67” was introduced. A later retirement age results in a shorter pension period or corresponding savings through deductions. The reduction in expenditure results in the low pension payments described in Chapter 2.1. However, some retirees also receive higher pensions because they have earned more earnings points.

On the revenue side, the statutory pension insurance is dependent on contributions. Contributions are currently paid by both the employee and the employer. These contributions must cover all expenses. The revenue can only be improved in relation to the expenditure by increasing the contributions, because the development of pensions is linked to the development of wages through the gross wage factor. However, a higher contribution rate burdens the young generation of workers and makes labour more expensive, which has a negative impact on employment and economic growth.

The inclusion of more employment relationships in the group of insured persons increases revenue. Better integration of the unemployed and employees in the low-wage sector into jobs subject to social security contributions avoids poverty in old age and builds up pension entitlements.[32] A higher proportion of women or people of retirement age would also increase revenue, especially in the period from 2030, which is critical for the finances of pension insurance.[33] In addition, an expansion of the compulsory insurance group, for example to civil servants and the self-employed, is conceivable.[34] Capital rent could also be used.

Like all models that increase the number of insured persons, such measures would provide relief in the medium term because revenue would be increased without currently causing expenses for self-employed pensioners, for example. In the context of the pension adjustment formula, however, such a change would also affect the annual pension adjustment and thus increase the expenditure for existing pensioners.[35]

The inclusion of other types of revenue also has an impact on the intra-generational structure of the statutory pension. It may change the average income by leaps and bounds. It also shifts the structure of pay points. But since, due to the principle of equivalence, every deposit is later to be matched by a payment, it does not solve the fundamental problem of pay-as-you-go pensions. It only postpones it insofar as the pension entitlements from these earnings points only become due when you retire. Since these pensions in turn have to be paid by the following generation, ultimately there is no way around an increase in the number of young people.

Finally, the tax subsidy, which would have to be taken from the federal budget and currently amounts to 69.7 billion euros, could be increased. This subsidy ties up considerable funds in the federal budget and should actually only be used to finance non-insurance purposes, but not to maintain the pension system itself. Therefore, supporting the pension fund with taxpayers’ money or, vice versa, withdrawing funds from the pension fund for the federal budget is out of the question. The circle of the insured is different from the totality of the taxpayers, and in budgetary terms the funds must be clearly separated from one another. For regulatory reasons, non-insurance benefits should disappear completely from the pension insurance, and the federal subsidy should be clearly limited.

Pension insurance as a pay-as-you-go system should only serve to stabilize income in old age and not be an instrument for promoting or upgrading any life model and would therefore have to do without extensive grants from the federal budget.

From this perspective, political proposals aimed at increasing pension entitlements for certain groups of insured persons also appear to be problematic. This is the case, for example, with the “lifetime benefit pension”, in which the pension entitlements of low earners or people with career breaks are to be upgraded. Such models are not accurate and do not lead to any substantial improvement compared to the status quo, but they put an additional burden on the expenditure side.[36]

In fact, none of the existing models are suitable for averting the decline in pension insurance caused by demographic change. Politicians can decide which factors (contribution rate, retirement age, pension level and tax subsidy) make them more or less worse. No solution will be satisfactory: a fundamental structural reform of the pensions system is required.

2.4. Structure of a family-friendly pension

In Chapter 2.1 it was stated that today’s pay-as-you-go pension scheme is an expensive but underperforming compulsory insurance, and that contributions will always go up and benefits will go down. Chapter 2.2 explained why this is the case: A pay-as-you-go system is inevitably dependent on active contributors and, above all, on a relatively stable ratio of contributors and beneficiaries. Due to a policy and a structure of the pension system that does not encourage families but rather encourages childlessness, this relationship gets out of whack from around 2025.[37] If nothing is changed in the distribution rules of the statutory pension insurance system, the pensions for all future pensioners will have to be lowered in the long term, the retirement age increased or the contributions increased if the system is not to be supported permanently via the tax subsidy.

This would further increase the injustice towards the families:

“The families finance their parents’ generation with their pension contributions. They pay the pensions of the future by raising their children. And in addition, they should finance their own pensions again by way of Riester savings. Two burdens are normal in the generational context. The third is one too many.

Instead of making an entire generation collectively responsible, the necessary pension cuts and the compensating Riester savings should be focused on the childless. Anyone who does not want or cannot have children can be expected to invest the money that others spend on raising children in the capital market in order to obtain an additional pension.”[38]

It is therefore necessary to differentiate the three-pillar model of old-age provision according to generative contributions. Anyone who has made generative contributions acquires a higher share of the pay-as-you-go pension paid by the following generations, into which they have also paid through their upbringing and corresponding loss of wealth. The generation contract remains intact (Figure 10).

Figure 10. The family-friendly pay-as-you-go pension as a generational contract

Source: MIWI Institute.

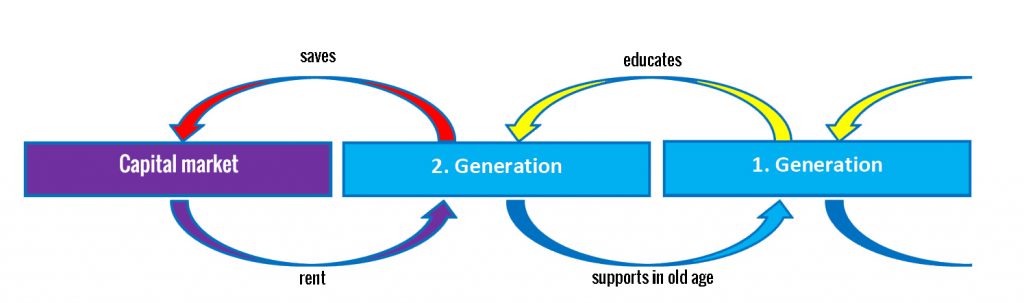

Those who do not continue to support this intergenerational contract save themselves the upbringing costs, but in return have to make private provisions because nobody can pay their pension. For childless people, the relationship is as follows (Figure 11).

Figure 11. The family-friendly pay-as-you-go pension with a capital backup for the childless

Source: MIWI Institute.

This differentiation between childless and parents is systemic and should not be misunderstood as a family policy measure. If parents are better off in the pay-as-you-go pension, this does not serve to achieve demographic, educational or labour market policy goals, but to reduce disadvantages – the continued existence of which, however, could counteract demographic policy goals. The so-called nursing judgment of the Federal Constitutional Court (2001, 1 BvR 1629/94 of April 3, 2001) also points in this direction. Here the court demanded a reform of the pay-as-you-go long-term care insurance and explicitly asked the legislature to examine the significance of the judgment for other branches of social insurance as well.[39]

The economic reality must not be lost sight of:

“Every generation grows old one day, and then it can only live if it made provisions for itself in its youth. Either it must have built up human capital by bringing children into the world and by educating them well. Or it must have saved and thus built up real capital, directly or indirectly, in order to live off the consumption of this capital. A generation that has neither human nor real capital must starve.”[40]

Generation-fair, family-neutral old-age provision must therefore include both human capital and real capital formation, but does not influence family planning, but reacts to it. The individual desire of couples to have or not have children must be respected. Those who decide in economic terms to form more human capital need to save less real capital in order to experience the same provision in old age.

At this point, however, the possibilities of measuring children according to their “human capital” end. Certainly, one child will later pay more into the pension fund than another due to higher earnings. However, the later “value” in society cannot be mechanically inferred from the extent of educational services or educational investments. Talent, motivation, incentive situations, other people, institutional conditions and also luck play central roles in a person’s development, so that the “quality” of a child should not be included in further considerations, only the number.[41]

What is interesting, however, is the level of expenditure that is made privately and by the public sector for children. The Scientific Advisory Board at the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs calculated this in an older study.[42] The results are quite fruitful for the pension discussion.

The calculations (figures in Deutschmark) refer to the prices and the family policy regulations of 1996, so they no longer reflect the reforms that took place after that. The private expenditures include money and time expenditure – however measured against very low income levels. Of the public expenditure, however, 10.0 percent to 23.5 percent arise as calculated tax waivers in connection with private time spent on children, and a further 13.5 percent to 17.1 percent are accounted for by constitutionally required tax reductions, i.e., they serve horizontally fair income taxation of families. Only 60.5 percent to 75.6 percent could be considered elements of family burden and benefit equalization.

Depending on the family situation, the parents bear about 50 to 60 percent of the costs. That is between around 200,000 Deutschmark and around 470,000 Deutschmark per child. By not having children, a childless person had these funds available to consume or to invest the money accordingly. The effect on the private pillar of old-age provision is significant: If a baby boomer couple in West Germany had not had a child in 1996, they would have remained childless instead (scenario married couple with child / West Germany, 470,079 Deutschmark) and would have had the money at the time invested at a low interest rate of 2 percent p.a. over 30 years, these savings assets for retirement in 2026 would have a value of 851,483.04 Deutschmark » 453,356.37 euros. The further life expectancy for both together is approx. 40 years, so that in this sample calculation each parent who has not become a parent receives a monthly pension of 944.49 euros – in addition to the statutory pension.

Not everyone has saved to this extent, but the model calculation shows what a striking financial difference it made for the next generation of pensioners whether they had children or not. If you lower the pension level for everyone equally, those who have had children will be punished twice. Due to the high expenses, they could not make provisions to the same extent as those who had few or no children.

Nevertheless, it would also be wrong to exclude childless people from the statutory pension insurance. Since the general public bears approx. 34 to 51 percent of the expenses for children, childless people, who are taxpayers along with parents, also contribute to a small extent to children’s expenses through tax transfers. This also justifies a – albeit small – right to be cared for later by these children.[43]

The burden of raising children for the pension can be balanced out in two ways: If one strives for constant pensions for childless people, they would have to contribute significantly more to the expenses for children through tax transfers. However, this would further burden the already extensive tax system and also require childless people and families alike to make extensive private provisions. This might be difficult. The other variant is that childless people continue to make contributions on a pay-as-you-go basis in order to finance the pensions of their parents’ generation. However, they would have to provide for their own pension outside of the pay-as-you-go system.[44]

There are various models in the literature on how pensions can be differentiated according to children (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Differentiation options when considering children

| Contribution differentiation | Performance differentiation | ||

| 1. Percentage

|

a. Total contribution

b. Employee contribution only

|

4. Granting of payment points

|

a. Without deductions

b. With discounts |

| 2. Absolute (“Contribution Bonus”)

3. Allowances on the assessment basis

|

5. Upgrading of payment points

6. Crediting of payment points under certain conditions 7. Differentiation of the pension adjustment |

||

Source: Althammer J., Mayert A. (2008).

For example, the contributions can be differentiated according to the number of children. If this also happens on the part of the employer, employees with children will be “cheaper” than without. The significant increase in administrative costs is disadvantageous. Allowances would also be possible. In both cases, the child savings would depend on the level of income. An absolute contribution bonus, on the other hand, would reduce the pension payment by a fixed amount.

In the case of performance differentiation, there is the possibility of granting additional payment points. This is already happening in the context of taking child-rearing periods into account. Mothers of children born after 1992 are credited with three earnings points. This gives them a “fixed amount” in addition to their entitlements generated from contribution payments. At the moment, this benefit is being replaced by the taxpayer as non-insurance. The granting of earnings points or a fixed child supplement departs from the principle of consolidating income in old age and rewards child-rearing services as a flat rate instead. In extreme cases, one parent can acquire pension entitlements simply by raising children.

The revaluation of earnings points and the crediting under certain conditions in turn raise the regulatory question of whether the distribution is fair. This means that certain work performances are rated higher than others; for example, low earners or single parents get higher entitlements at the expense of those who have paid more. This in itself is unfair. Furthermore, the question remains as to how earnings points are distributed between the two parents and whether they can be devalued by the pension type factor in the case of survivor’s pensions. This means that raising children would be worth less if the parent who received the credit points dies. A differentiation of the pension adjustment or the pension calculation appears to be a sensible idea, which will be pursued further in this concept.

The proposals in the literature differ significantly.

Althammer J., Mayert A. (2008) are examining an extension of the child-rearing periods in the GRV and calculate that it is possible to issue additional payment points.

The AfD parliamentary group in the Thuringian state parliament proposes both a contribution differentiation (0.5 percent saving up to the 3rd child) and a flat-rate child’s pension of 90 to 125 euros.[45]

Kochskamper S. (2015) wants to redefine the corner pensioner. The full pension should only be given to those who have brought up two children. Persons with fewer children receive discounts, with more children surcharges.

Sinn H.W. (2013) considers an increase in the retirement age to be unavoidable, recommends compulsory partial funding and is developing a new three-pillar system: the statutory pension will be retained, the contribution rate and percentage federal subsidy will be frozen. As a result, the pension level drops very low. Those who have brought up children receive a new, pay-as-you-go pension, which is paid by everyone, which raises the total pension together with the previous old pension to the current level. The third pillar is mandatory Riester savings of 6 to 8 percent of wage income, which also raises the pension to today’s level. Everyone is obliged to do this. For each child born, up to the third child, one third of the savings amount is paid out and the pension provision is taken over by the second pillar redistribution pension.

So, there is no shortage of ideas for structuring pensions that are fair to the generations. It’s time to pour this into a working concept.

3. The 20/40/60 pension

The statutory pension is wasting away. Pensioners can no longer expect an adequate claim. Germany’s pension system urgently needs a far-reaching, systematic reform – away from Riester factors and cuts towards genuine intergenerational equity. We need a strong three-pillar system of statutory, company and private pensions with a strong statutory pension as the first pillar – for all people who have made the necessary contributions to this.

The concept presented here has high performance and quality standards. It will work today, will be able to fully develop in 2030 and in 2060 it will still secure people’s pensions unchanged. It will enable

a corner pensioner

with a fixed contribution rate of 20 percent

and a fixed tax subsidy of 20 percent

after 40 years of contributions

a net pension level of more than 60 percent.

To do this, the statutory pension must be restored to what it was originally intended to be: a three-generation contract. And it must go back to being a purely performance-related pension scheme. Non-insurance benefits, special payment points and upgrading factors are outsourced and removed from the statutory pension.

The concept of the three-generation contract states that a pay-as-you-go system actually always describes relationships between three generations. Working people help their parents’ generation as they get older, but they also have to raise children, who in turn finance their parents’ pensions through their contributions. The pay-as-you-go pension therefore only works with both components: the contributions to the parents and the child-rearing expenditure.

The pension insurance ignores the generative contribution in its current form almost completely.

However, the 20/40/60 pension takes this important connection into account in the form of a child factor. The more children someone has, the higher the factor. The factor 1 is given to those who have at least 2 children and have thus fulfilled the full generative contribution. Unlike today’s “mother’s pension”, however, it is not possible to acquire pension entitlements without gainful employment just because you have raised children. The pension serves to stabilize income in old age. Anyone who has never generated income has nothing to stabilize. Pension policy is not family policy, even if it is family-friendly.

Anyone who has no children can no longer fully rely on the transfer pension. Therefore, private provision is also an important element of the 20/40/60 pension. If you have two children, you should be able to save 20 percent of your pension capital funded, if you have one, 40 percent, if you don’t have at least 60 percent. Especially for those who have no children – regardless of whether they want to or not – it is true that they have to build up their own capital for old age. In principle, this has been known since Riester, and it is fair. Because those who have no children usually have significantly more money available for private provision than a comparable worker with children, and has not made any generative contribution to the pay-as-you-go pension. Therefore, the following applies: The fewer children someone has, the more personal responsibility they have for their own retirement provision.

The 20/40/60 pension therefore makes private provision easier and contributes to its spread. The promotion of expensive and unprofitable Riester savings contracts will be canceled without replacement. They are replaced by a simple system of co-financing by the employee and employer in an optional supplementary pension fund. This is a public capital-based pension fund that you automatically become a member of. However, if you do not want to use this fund, you can switch to a private product at any time or purchase a property for old-age provision. The 20/40/60 pension does not patronize anyone in their individual investment decisions. However, it encourages people to think about retirement and makes it easier for workers to have consistent capital-funded retirement, who are more likely to be unemployed or work in low-wage jobs. You can still save in the optional additional insurance without having to regularly use long-term savings plans. The pension for surviving dependents is also regulated in the optional supplementary pension.

The goal is that everyone has the opportunity to receive a net pension level of 60 percent of the average earned income through the different forms of provision (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Structure of the support pillars of the 20/40/60 pension in 2030

| 0children | 20 percent | 50 percent | 30 percent |

| 1 child | 70 percent | 25 percent | 5 percent |

| 2 children | 95 percent | 5 percent | Not necessary |

| 3 or more children | 115 percent or more | Not necessary | Not necessary |

Source: MIWI Institute.

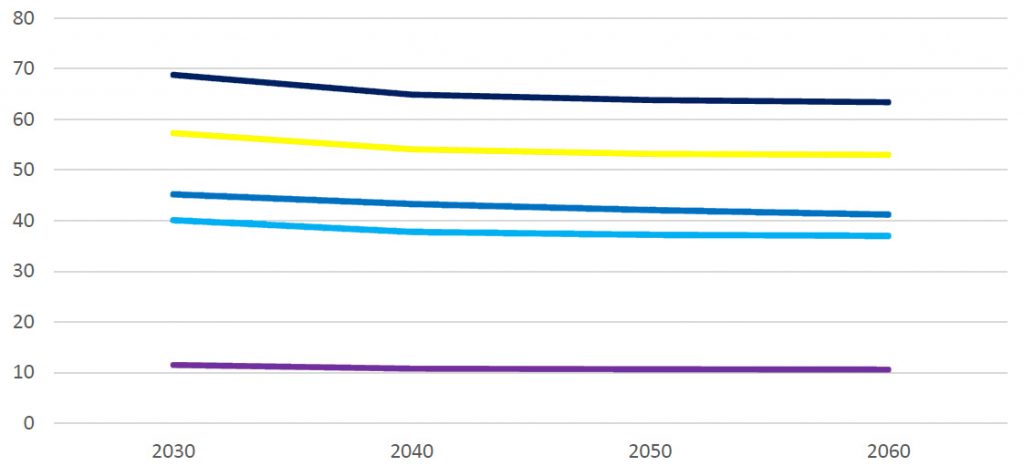

The importance of the pillars varies depending on the extent of your own child-raising expenditure: the pay-as-you-go pension is all the more powerful the more children the pensioner has raised. By 2060, the pay-as-you-go pension will be weaker due to demographic change (which can still be stopped!), but with a constant 20 percent pension contribution and 20 percent state subsidy, good pension quotas can be maintained (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Structure of the support pillars of the 20/40/60 pension in 2060

| 0children | 15 percent | 50 percent | 35 percent |

| 1 child | 45 percent | 30 percent | 25 percent |

| 2 children | 65 percent | 30 percent | 5 percent |

| 3 or more children | 80 percent or more | 20 percent | Not necessary |

Source: MIWI Institute.

For comparison: In 2060, the statutory pension insurance will only offer a pension level of 41.2 percent with a contribution rate of 27.2 percent and a state subsidy of 36 percent. A levy of more than a quarter of earned income and a federal subsidy in the three-digit billion range are offset by poverty pensions without reform.

3.1. The corner pensioner in the 20/40/60 pension

The so-called corner pensioner describes a model pensioner who has had a kind of absolutely average career. Today’s corner pensioner has worked for 45 years and earned exactly the average salary, i.e. earned exactly one payment point every year. The official pension level describes the ratio of your (average) pension to average earnings in percent. It is currently 48.2 percent.

The corner pensioner of the 20/40/60 pension is replaced by another model: The 20/40/60 corner pensioner has earned average earnings for 40 years and paid 20 percent of it, i.e., earned 40 earnings points. In addition, he has three children. The 20/40/60 pension ensures that someone who has worked extensively to support a family can expect at least a 60 percent level of security.

3.2. The 20/40/60 pension as a generation-fair pension

In order to achieve this goal, the pay-as-you-go pension will be rebuilt to suit the generations and designed as a real three-generation contract. As demonstrated in the scientific part, a large number of economists recommend differentiating pensions according to the number of children. A pay-as-you-go pension is not a capital-funded provision or a pension fund where money is put aside and then you get it. Rather, the contributions are immediately distributed to the parents’ generation as maintenance, and in Germany far too few workers will soon have to support far too many people of retirement age. Many of these people have renounced children due to wrong family and pension policies and better conditions for childless people. However, the generative contribution is missing. A pay-as-you-go system can only work if there are always enough contributors. Therefore, the pay-as-you-go system, in its crisis, must begin to take this factor into account mathematically as well.

With the 20/40/60 pension, all non-insurance benefits will first be removed from the pension insurance and regulations that award additional earnings points for something (e.g., child-rearing periods) will be abolished. Circumstances worthy of pension policy are no longer represented by fictitious earnings points, but by the state making provisions in the optional supplementary pension plan. In this way, the redistributive pension completely implements the principle of equivalence from its own contributions and performance.

The formula for calculating the pension adjustment is significantly simplified by eliminating the Riester factor and the sustainability factor. These two factors were introduced to automatically slow down pensions in the face of demographic change. However, they punish those who have children and have made provision for the redistribution pension twice over, because the pension does not increase for them either. In the 20/40/60 pension, the calculation of the current pension value is based exclusively on the actual value of a payment point according to the income situation and the total number of payment points.

The generative contribution is represented by a child factor in the pension formula:

Monthly gross pension = earnings points x entry factor x current pension value x pension type factor x child factor

The earnings points collected and the current pension value result in the pension without factors.

The entry factor (currently: reduction of 0.3 percent per month of early retirement, increase of 0.5 percent per month of late receipt of pension) is designed and checked in the same way for the redistribution pension and the optional supplementary insurance.

The pension type factor (retirement pension 1.0, reduced earning capacity 1.0 or 0.5, widow’s pension 0.55, full orphan’s pension 0.2, half orphan’s pension 0.1) is increased again to 0.6 for the widow’s/widower’s pension in order to increase security for e.g. women who have brought up children.

The child factor is new to the 20/40/60 pension and takes into account the generative contribution of the pensioners. The childless only contribute to raising children through the taxes that are paid by the childless and parents. The public expenses for bringing up children are between about 40 and 50 percent, depending on the type of family. The remaining expenses, approx. 200,000 euros per child, are borne by the parents themselves and they cannot invest this money in private provision. The child factor takes this connection into account, the relatively high costs for a first child and the fact that two to three children are needed to maintain the pay-as-you-go system. Therefore, the factor for two children is 1.0. A basic pensioner who has worked for 40 years and raised three children can maintain the net pension level of 60 percent until 2060 (Figure 15).

Figure 15. Child factor in the 20/40/60 pension

| Number of children | Child factor |

| Childless | 0.2 |

| 1 child | 0.7 |

| 2 children | 1.0 |

| 3 children | 1.2 |

| Every further child | + 0.2 |

Source: MIWI Institute.

The child factor decreases by 0.01 for each complete year within the first 18 years of a child’s life that no child support was or was required to be paid. Such a case can occur, for example, in the event of later adoption, the death of the child or a refusal to provide care or maintenance. For fathers, the acknowledgment of paternity is a prerequisite for the allocation of the child factor. If the pension recipient dies while the child is a minor, there is no deduction from the child factor in the survivor’s pension.

Only the number of children is taken into account, not their “quality” or later contribution to society. This would not make economic sense to record.

With its child factor, the generation-fair pension solves a central problem of the previous statutory pension: the pension was actually an incentive against children. Since the generative contribution was initially systematically disregarded and was only rewarded with 1-3 earnings points through later reforms, childless people were fundamentally disadvantaged: they could work in pairs, realize unlimited career opportunities, earn high salaries, pay high contributions – and collect the highest pensions. However, those who made sure that these pensions can be paid at all are often on the losing side today because they were not able to take advantage of career opportunities to the same extent, parents stayed at home to raise children or only one full-time and one part-time job was filled. The generation-fair pension makes no family policy. This is also made clear by the fact that remuneration points are no longer awarded for education. Rather, the child factor serves to include the “human capital investment”, which makes pension payments possible at all, in the pension calculation. This does not give parents any advantages, but compensates for the burden. With a generation-fair pension, the state does not make family policy. On the contrary, it withdraws from family politics:

“Today, the state intervenes massively in family planning via the pension system by socializing the children’s contributions to the pension insurance and thus driving the natural economic motives for wanting children out of people’s minds. This massive state intervention took place for other reasons, certainly not with the intention of reducing the number of children. But the fact is that it has this effect and distorts the fertility decision. In this respect, politics today can no longer avoid the question of how to reduce the unwanted distortions. Not more, but less state influence on family planning is required, and that requires changing the pension system to include a child component.”[46]

The model calculations also show that taking the child component into account also solves the problem of the statutory pension, of being able to make appropriate payments with the ever-increasing old-age quotient. If there is no child component, i.e. everyone has a child factor of 1.0, the pension level must drop to below 40 percent or the contributions must rise to over 30 percent. If, on the other hand, the cause (childlessness) and the effect (decrease in payments relative to the number of pensioners) are combined by using a child factor, the pension level for families remains at a comparatively high level. The cut will be applied to those who, systemically speaking, are responsible for it.

3.3. Model calculations

The following model calculations are based on the projections of the Deutsche Rentenversicherung up to 2030 and by Prof. Martin Werding up to 2060.[47],[48] Precalculating the number of children of future pensioners is extremely difficult because there is hardly any suitable data for this; it must be estimated from the information provided by the Federal Statistical Office for all families. However, it can be assumed that the proportion of childless pension recipients will increase from the current 12 percent to up to 24 percent in 2060. Adding in the proportion of men and women who have only one child, it is expected that by 2060 more than half of pensioners will have only one or no children.

Figure 16. Old-age pensioners in Germany, by number of children (2000 – 2060)

Total number of retirees (in mln persons, shades of blue, left axis); share of childless retirees (in percent, red, right axis); no children (light blue), one child (blue), 2 or more children (dark blue). | Source: Werding M. (2015).

The new generation-fair pension turns away from attempts to keep the contribution rate stable via damping factors in the pension adjustment. Instead, in the 20/40/60 system, both the pension contribution and the tax subsidy are fixed at 20 percent. At the same time, a pension level of 60 percent can be achieved for the basic pensioner in all simulated years. The following overview compares the performance of the 20/40/60 pension with today’s statutory pension, with and without Riester cushioning (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Financing and pension level of the statutory pension insurance in comparison to the 20/40/60 pension (2020 – 2060, in percent)

| Year | Statutory pension insurance without reform | Statutory pension insurance without Riester | 20/40/60 pension | ||||||

| Contribution rate | Tax subsidy | Pension level | Contribution rate | Tax subsidy | Pension level | Contribution rate | Tax subsidy | Pension level | |

| 2020 | 19.6 | 33.8 | 47.1 | 20.1 | 33.4 | 48.5 | 20 | 20 | 60 |

| 2030 | 21.3 | 33.4 | 45.2 | 22.7 | 33.0 | 48.0 | 20 | 20 | 60 |

| 2040 | 23.7 | 34.1 | 43.3 | 25.9 | 33.7 | 47.3 | 20 | 20 | 60 |

| 2050 | 25.9 | 34.7 | 42.1 | 28.7 | 34.3 | 46.9 | 20 | 20 | 60 |

| 2060 | 27.2 | 36.0 | 41.2 | 30.7 | 35.9 | 46.7 | 20 | 20 | 60 |

Source: MIWI Institute.

It can be assumed that the child factors in the 20/40/60 pension will only be gradually introduced by 2030. Families with many children are therefore gradually being adjusted upwards, while those without children are gradually being adjusted downwards.

The following table shows how much pension an average pensioner can expect in the 20/40/60 pension, depending on the number of children, in values for the year 2030. The estimates from Bundesregierung (2017) used for these values. In the lower, i.e., pessimistic, wage variant, it expects revenue of 461.3 billion euros in 2030, of which 111.1 billion euros are tax subsidies. The tax subsidy in the 20/40/60 model is only 20 percent, thus revenue will decrease to 437.75 billion euros. From then on, 440 billion euros are expected. In addition, 18,253 equivalence pensioners are expected in 2030. The deterioration of the old-age dependency ratio over the years taken from Werding M. (2013) is taken into account by calculating it as an increase in the number of equivalence pensioners. The average pension is determined by dividing the revenue by the number of equivalence calculators and then converting it to the child factors. The distribution of old-age pensioners according to the number of children is based on the Werding model, see diagram above, whereby, analogous to the figures from the German Federal Statistical Office, it is assumed that there are three times as many families with 2 children as with 3 children. Since the values are deliberately set low, the model calculation shows what can at least be expected in the 20/40/60 pension. In addition, it does not reflect the expected higher fertility due to the pension reform but continues to assume 1.4 children per woman. This calculation is primarily used to show the net pension level in the 20/40/60 pension. Since there are no forecasts for the amount of the contributions after 2030, these assumptions are based on values for the year 2030; so, they do not take into account inflation, wage increases, etc. (Figure 18).

Figure 18. Estimated pension level in the 20/40/60 pension (2030 – 2060)

|

2030 |

||||||||

| Equivalent pensioners in thousands | 18253 | |||||||

| Average pension in euros | 24106 | |||||||

| Pensioner type | Childless | 1 child | 2 children | 3 children | ||||

| Share (in percent) | 16 | 21 | 47 | 16 | ||||

| Child factor | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1 | 1.2 | ||||

| Annual average pension | 5732.97 | 5732.97 | 5732.97 | 5732.97 | ||||

| Gross pension level (in percent) | 10.61 | 10.61 | 10.61 | 10.61 | ||||

| Net pension level (in percent) | 11.46 | 11.46 | 11.46 | 11.46 | ||||

|

2040 |

||||||||

| Equivalent pensioners in thousands | 20638

|

|||||||

| Average pension in euros | 21320 | |||||||

| Pensioner type | Childless | 1 child | 2 children | 3 children | ||||

| Share (in percent) | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | ||||

| Child factor | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1 | 1.2 | ||||

| Annual average pension | 5311.64 | 5311.64 | 5311.64 | 5311.64 | ||||

| Gross pension level (in percent) | 9.83 | 9.83 | 9.83 | 9.83 | ||||

| Net pension level (in percent) | 10.81 | 10.81 | 10.81 | 10.81 | ||||

|

2050 |

||||||||

| Equivalent pensioners in thousands | 22426

|

|||||||

| Average pension in euros | 19620

|

|||||||

| Pensioner type | Childless | 1 child | 2 children | 3 children | ||||

| Share (in percent) | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | ||||

| Child factor | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1 | 1.2 | ||||

| Annual average pension | 5088.32 | 5088.32 | 5088.32 | 5088.32 | ||||

| Gross pension level (in percent) | 9.42 | 9.42 | 9.42 | 9.42 | ||||

| Net pension level (in percent) | 10.64 | 10.64 | 10.64 | 10.64 | ||||

|

2060 |

||||||||

| Equivalent pensioners in thousands | 23845 | |||||||

| Average pension in euros | 18453 | |||||||

| Pensioner type | Childless | 1 child | 2 children | 3 children | ||||

| Share (in percent) | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | ||||

| Child factor | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1 | 1.2 | ||||

| Annual average pension | 4962.17 | 4962.17 | 4962.17 | 4962.17 | ||||

| Gross pension level (in percent) | 9.18 | 9.18 | 9.18 | 9.18 | ||||

| Net pension level (in percent) | 10.56 | 10.56 | 10.56 | 10.56 | ||||

Figure 18. Estimated pension level in the 20/40/60 pension (2030 – 2060, in percent of average prior income)

Statutory pension insurance (blue), childless (purple), 1 child (light blue), 2 children (yellow), 3 children (dark blue). | Source: MIWI Institute.

As can be seen from the tables, even with the poor old-age dependency ratio of 2060, a pension that is fair to the generations can ensure that those who have children are well taken care of in the statutory redistribution pension: For parents of one child, the level roughly corresponds to the Riester dampening of today. Parents of two children remain 4-5 percent above the current pension level. Parents of three children or more experience an actual stabilization of income in old age without having to worry about their retirement provision: In accordance with the nature of the three-generation contract, they have secured their livelihood in old age by investing in human capital. Childless people are only taken into account in the generation-fair pension to the extent of their share in raising children via tax transfers. As a result, their redistribution pension only covers about a sixth of their pension needs. They have to compensate for this with additional old-age provision.

3.4. Retirement entry

Since the pension insurance finances itself, no further increase in the retirement age is necessary. This decision remains in political hands. One family support measure would be to stick to the retirement age of 67, with parents being able to retire one year earlier for each child. Anyone who has worked 45 years, and thus 5 years longer than the new corner pensioner, should definitely be able to retire without deductions. The pension entitlement period also includes periods of training in a training occupation, in traineeships, traineeships or in the first degree to the extent of the standard period of study and subject to the successful completion of the degree.

3.5. Financing and contributions

The 20/40/60 pension is funded 20 percent from the federal grant. The contribution rate for statutory pension insurance is also set at 20 percent, with 10 percent being borne by the employee and 10 percent by the employer. The self-employed pay the full 20 percent share. The dynamic contribution assessment limit is maintained.

This represents a relief for the younger generation in particular: In all scenarios that would retain the existing statutory pension scheme, the contribution is well over 20 percent. The taxpayer community will also be relieved, because the federal budget will save around 15 billion euros annually in 2030. There is no additional financing requirement.

3.6. The second pillar: the optional supplementary insurance

Due to the negative effects of demographic change, no modern pension concept can avoid private provision. Future pensioners with few children in particular must invest in real capital and make provisions for old age. However, the state-funded Riester programs are unsuitable for this because they are expensive and hardly generate any returns. Therefore, these subsidies will be cancelled without replacement.

The optional supplementary insurance integrates all employed persons – including civil servants and the self-employed – in Germany into their private provision. If you don’t want to, you can opt out. By default, however, everyone is in.

The optional supplementary insurance includes many types of private provision:

- the statutory supplementary insurance with the German Federal Pension Insurance is newly created and is the standard.

- voluntary supplementary insurance

- Riester savings plans

- company pension scheme

- capital funds and savings plans

- real estate for retirement provision.

A quarter of the pension can be saved by investing as little as 4 percent of income. This pension model is therefore particularly interesting for those who have no or only one child.

The optional additional insurance accounts for a total of 5 percent of the income. 2.5 percent is borne by the employee and 2.5 percent by the employer and paid directly into the fund. A higher employee share is possible at any time. The employer contribution does not increase.

The optional supplementary insurance is an “opt-out model”. This means that every employed person is initially insured by default but can opt out at any time. The advantage of this is that it significantly increases the savings rate. Anyone who opts out saves their employee share of 2.5 percent. The saved employer contribution of 2.5 percent is not paid out to the employee. In addition, getting out reduces the basic security in old age. Those who earn little otherwise have no motivation to save for old age: they have to fear falling into the basic social security system. Those who have worked and saved should have more than those who have not.

The employer insures the employee as standard in the company pension scheme offered by the company or in the new statutory supplementary insurance with the German pension insurance. Statutory supplementary insurance is a company-independent occupational pension scheme at federal level. It invests the money in safe papers in order to preserve the capital stock in any case. The expected return on statutory supplementary insurance is therefore also relatively low. Statutory supplementary insurance is also provided – at a low level – in the case of unemployment. The employee can also take a break in between.

However, if you want, you can also invest privately in capital and invest the 5 percent freely. Such investments can be fund savings plans, Riester contracts or real estate for old age. The employer then directs their share directly into the product. However, if he has doubts that it really serves to provide for old age, he can still transfer the employer’s share to the statutory optional additional insurance after prior consultation with the employee. In the case of basic security, the invested capital is protected against sale.

Families with at least two children can also have the capital paid out from the optional additional insurance before they retire, since the redistributive pension promises adequate security in old age. The regulations on retirement, reduced earning capacity and survivor benefits in public supplementary insurance products are identical to the regulations in the redistribution pension. In this way, it also compensates for the weakness of some private products that do not insure against the risk of reduced earning capacity or death.

The optional additional insurance system is therefore an institution that does not use tax money to promote certain financial products, but leaves the investment decision entirely in the hands of the individual. However, it motivates people to make provisions for their old age, since those in employment are insured as standard in the optional additional insurance. Anyone who wants to change this is forced to cancel the optional additional insurance and automatically has to deal with their income situation in old age.

3.7. Everyone pays in: the pension as employment insurance

From the introduction of the 20/40/60 pension, civil servants and the self-employed, i.e. all employed persons, should also be included in the statutory pension insurance. This not only has positive effects for the peak phase of the demographic crisis from 2030, but is simply a question of justice. Current civil servant pensions range up to 70 percent of the last salary, which the statutory pension insurance can no longer reflect. However, pension provisions are not always as extensive as they should be. The inclusion of everyone in the statutory pension makes economic sense, protects the self-employed in particular from a pension gap in old age and is intragenerationally fair. It also justifies the 20 percent tax subsidy that the redistribution pension requires.

3.8. If it’s not enough: basic security in old age

Despite the provision in the statutory pension insurance and the optional supplementary insurance, it can happen that there is not enough in old age. In this case, the tax-financed basic security should provide the social benefits with a small surcharge, which takes into account the earnings points received in the redistribution pension and the private provision in the OZV. Anyone who has assets should not be forced to give up and sell everything first, but should also be able to receive basic security as a “social loan” at the base interest rate, with the state accessing these assets after the death of the pensioner or the pensioner couple.

3.9. Final remarks

The core task when developing a pension concept is always to keep the dignity of people in old age in mind. Anyone who has worked all their life and thus contributed to the success of society has the right to live decently in old age.