_ Gene Ambrocio, research economist, Bank of Finland; Andrea Ferrero, professor, University of Oxford; Esa Jokivuolle, head of research, Research Unit, Bank of Finland; Kim Ristolainen, postdoctoral researcher, Department of Economics, University of Turku. VoxEU, 21 July 2022.

A key question for any inflation-targeting framework is what the inflation target should be. This analytical note reports findings from a survey of leading economists from around the world on the inflation target and related monetary policy issues. Overall, there was a strong preference for the status quo, with participants seeming to perceive high costs in terms of credibility from changing the current inflation target. However, participants concerned about the zero lower bound on the nominal interest rate were more likely to favour raising the target.

…

A key question for any inflation-targeting framework is what the inflation target should be. Theoretical and practical considerations made central banks in advanced economies converge on a 2 percent inflation rate target. However, the consequences of the Global Crisis, with years of ‘low-flation’ and the effective lower bound (ELB) constraining central bank policy rates, have challenged the consensus. One proposal to limit the repeated occurrence of ELB episodes in the future is to raise the central bank inflation target (Blanchard et al. 2010, Ball 2013, Krugman 2014).1

Our new research (Ambrocio et al. 2022) contributes to this debate with an expert survey on the inflation target and related monetary policy issues, run at the end of 2020, with responses from more than 600 economists worldwide.2

Our four main findings are:

1. Most respondents prefer the central bank to have other objectives than just price stability.

2. Supporters of inflation targeting express a significant preference for maintaining the current numerical target. Conditional on supporting a change, however, the preference is two to one in favour of raising the current target.

3. The main reason to keep the current target appears to be the credibility cost for the central bank, while the main reason to raise the target is the concern for the ELB.

4. Only 25 percent of respondents would increase the inflation target following a permanent decline of the equilibrium real interest rate (r*).

Central bank objectives

Following the high inflation experience of the 1970s, the focus of monetary policy increasingly shifted towards price stability (Meltzer 2009). However, following the 2008 crisis – an episode with relatively stable prices but a high degree of financial turmoil and large unemployment fluctuations – several critics have questioned the right balance between price stability and the other objectives of monetary policy (DeGrauwe 2008, Leijonhufvud 2008).

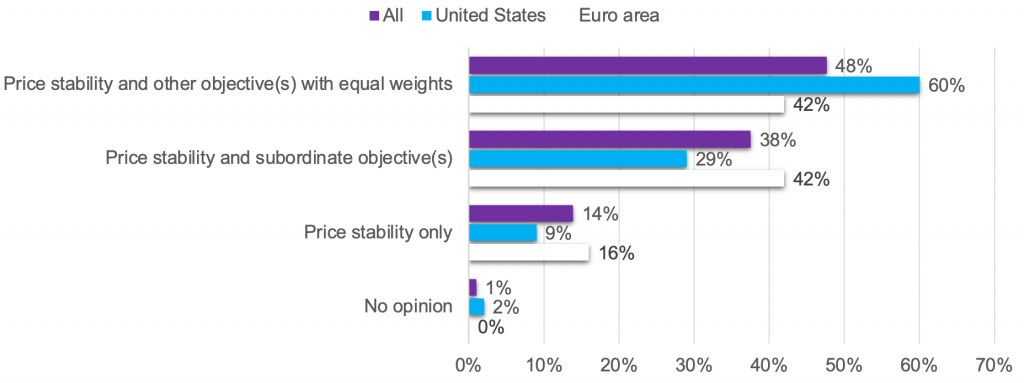

Against this backdrop, we asked participants about their views on the monetary policy mandate. Only about 14 percent of the respondents support a sole price stability objective (see Figure 1). Most prefer the central bank to have also other objectives, either with equal weights with price stability (48 percent) or subordinate to price stability (38 percent). The Fed-style ‘dual mandate’ gets significantly more support from US respondents. Conversely, euro area respondents are evenly split between supporting the ECB’s ‘subordinate mandate’ and a dual mandate. In written responses, the most popular other objective is (un)employment, although only slightly more than 40 percent of the respondents would make a target for the secondary objective explicit, like for the inflation rate (see Figure 2 in Ambrocio et al. 2022).

Figure 1. What should the central bank’s objective(s) be?

Potential alternatives – such as the price level, the level of nominal GDP or its growth rate – only received minor support.

In a subsequent question regarding the specific price index that the central bank should use, we find almost the same support for headline and core CPI (27 versus 25 percen t) as the price index to target. However, a much stronger preference for the core index (CPI = 27 percent, PCE = 33 percent) emerged in the US sub-sample.

Views on the inflation target

Almost 80% of the respondents want their central bank to have an inflation target.3 To make answers concerning the preferred numerical inflation target comparable across countries, we define:

PREFERRED CHANGE OF INDIVIDUAL i = PREFERRED INFLATION TARGET OF INDIVIDUAL i – ACTUAL INFLATION TARGET OF COUNTRY WHERE i RESIDES

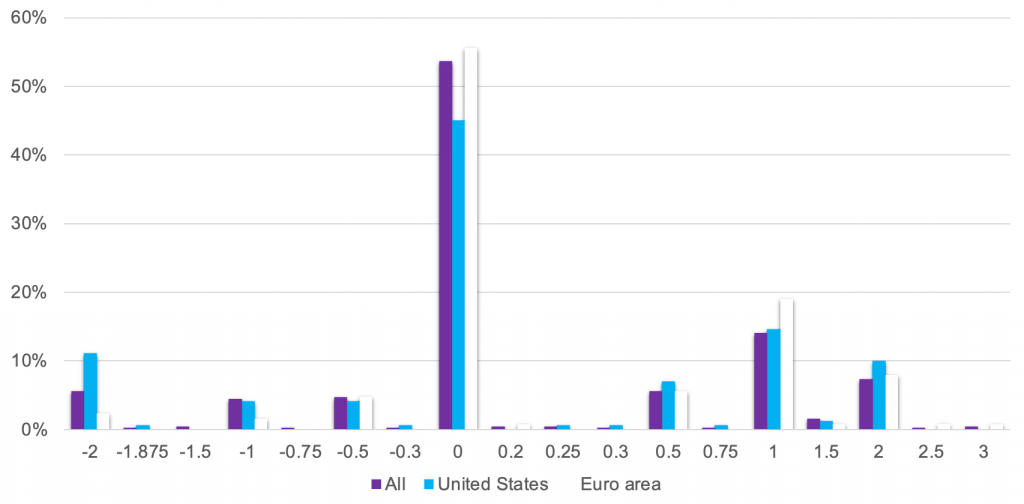

Figure 2. Preferred change in the inflation target

Among respondents from inflation-targeting countries or regions, more than half (54 percent) support the central bank’s current target, about 30 percent would prefer a higher target, while 16 percent would choose a lower target (see Figure 2). The median preferred deviation from the current target is one percentage point in either direction.4

The cost of changing the target

Among the potential costs of changing the inflation target, the credibility of the central bank is a chief concern. A change of the target may unmoor inflation expectations, especially if the private sector starts believing that further changes may occur again in the future.

We investigate indirectly to which extent such costs influence the respondents’ views by positing a hypothetical scenario in which the central bank starts inflation targeting with a clean slate. About 12 percentage points fewer respondents prefer no change in this hypothetical scenario than in current conditions. Most of those who change their view prefer to increase the target. Our conjecture is that the loss of credibility is the main cost of changing targets in current conditions.5

The determinants of the optimal inflation target

Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe (2010) have recently surveyed the academic literature on the optimal rate of inflation, which dates back at least to Friedman (1969).6 We asked respondents to ‘rank’ the factors determining the inflation target in terms of importance. We then considered the average scores by subsamples, split by preference for either keeping, decreasing, or increasing the current target. The ELB on monetary policy rates came out as a significantly more important factor for supporters of a target increase than for supporters of no change (see Table 4 in Ambrocio et al. 2022).

The equilibrium real interest rate

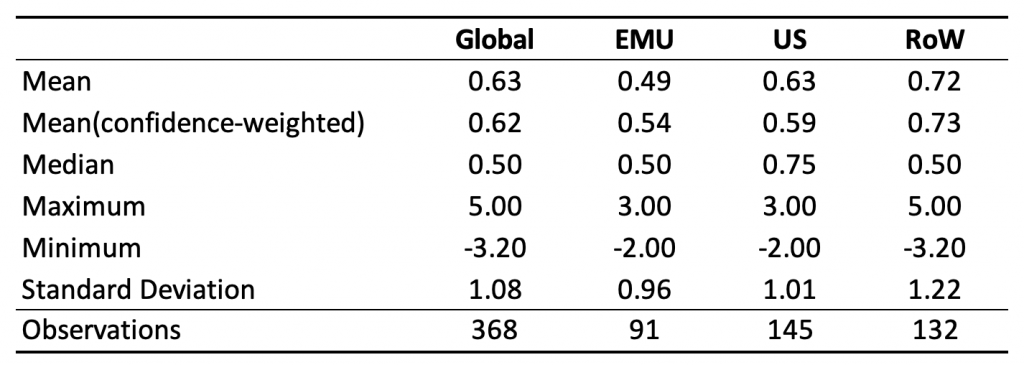

The debate on the secular decline of r* (Summers 2014), tightly related to the frequency of the ELB episodes, is a key factor behind the renewed interest in the optimal choice of the inflation target (Kiley and Roberts 2017).7 We find the respondents’ average estimate of r* in the full sample to be 0.6 percent (see Table 1). However, views on r* do not predict a preference for increasing the inflation target, not even among respondents who believe in a negative relationship between r* and the optimal inflation rate (Andrade et al. 2019).

Only 25 percent of the survey participants would like to increase the inflation target in response to a hypothetical one percentage point permanent decline in r*, while 34 percent would leave the target unchanged in such a scenario.8 This provides further evidence that many experts envision significant costs of changing the inflation target.

Table 1. Views on r*

On public debt and inflation

The high levels of government debt in many jurisdictions have rekindled discussions on the interaction between monetary and fiscal policy. Policy measures taken in response to the Covid crisis have further raised debt levels and thus made the issue even more pressing.9 As Teles and Tristani (2021) have pointed out, the financing of large fiscal shocks can also have implications for optimal inflation.

Motivated by such considerations, we investigate whether the public debt to GDP ratio in the respondent’s country of residence predicts a preference to raise the inflation target and find that to be the case.10 One interpretation is that a higher level of debt may require a higher inflation target to reduce its value in real terms.11

Conclusions

While the recent high-inflation environment may put the debate on changing the inflation target aside, our results should remain nonetheless useful to think about the trade-offs associated with changing the inflation target in the future.

References

Adam, K, E Gautier and H Weber (2022), “Why central banks should aim for a positive inflation target”, VoxEU.org, 6 June.

Ambrocio, G, A Ferrero, E Jokivuolle and K Ristolainen (2022), “What should the inflation target be? Views from 600 economists“, CEPR Discussion Paper 17289 and Bank of Finland Research Discussion Paper 7/2022.

Andrade, P, J Galí, H Le Bihan and J Matheron (2019), “The optimal inflation target and the natural rate of interest”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity Fall 2019: 173-249.

Ball, L (2013), “The case for 4% inflation”, Central Bank Review 13: 17-31.

Bernanke, B (2010), “The economic outlook and monetary policy”, speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium.

Blanchard, O, G Dell’Ariccia and P Mauro (2010), “Rethinking macroeconomic policy”, Staff Position Note 10/03, IMF.

Blinder, A (2000), “Central-Bank Credibility: Why do we care? How do we build It?”, American Economic Review 90: 1421-1431.

Cochrane, J (2021), “The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level”, Unpublished.

DeGrauwe, P (2008), “There is more to central banking than inflation targeting“, VoxEU.org, 14 November.

Friedman, M (1969), The Optimum Quantity of Money, Mcmillan.

Ehrmann, M, S Holton, D Kedan and G Phelan (2021), “Monetary policy communication: Perspectives from former policy makers at the ECB”, ECB Working Paper 2627.

Kiley, M and J Roberts (2017), “Monetary policy in a low interest rate world”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity Spring 2017: 317-372.

Krugman, P (2014), “Inflation targets reconsidered”, Unpublished.

Leijonhufvud, A (2008), “Central banking doctrine in light of the crisis“, VoxEU.org, 13 May.

Meltzer, A (2009), A history of the Federal Reserve, Volume 2, Book 2, 1970-1986, University of Chicago Press.

Reichlin, L, K Adam, W J McKibbin, M McMahon, R Reis, G Ricco and B Weder di Mauro (2021), “The ECB strategy: The 2021 review and its future“, VoxEU.org, 1 September.

Reichlin, L, G Ricco and A Tuteja (2022), “The two-dimensional feature of ECB monetary policy”, VoxEU.org, 14 April.

Schmitt-Grohé, S and M Uribe (2010), “The optimal rate of inflation” in B. Friedman and M. Woodford (Eds.), Handbook of Monetary Economics, Volume 3, Chapter 13, pp. 653-722. Elsevier.

Summers, L (2014), “Reflections on the `New secular stagnation hypothesis’”, in C Teulings and R Baldwin (eds), Secular Stagnation: Facts, Causes and Cures, Chapter 1, pp. 27-38. CEPR Press.

Teles, P and O Tristani (2021), “The Monetary Financing of a Large Fiscal Shock”, Bank of Finland-CEPR 2021 Conference on New Avenues for Monetary Policy.

Endnotes

1 In line with the view of increasing the target, the ECB slightly raised its inflation target in July 2021 from “close but below 2%” to 2%. Despite keeping the target unchanged at 2%, the Fed adopted an average inflation targeting framework, which requires to “make up” periods of below-target inflation with periods of inflation above target (and vice versa). See here and here, respectively (see also Reichlin et al. 2021). Bernanke (2010) notes that a higher inflation target also carries costs.

2 Our sample comprises all top 10% researchers according to RePEc, as well as the CEPR and NBER research fellows in the fields most closely related to these issues. Most participants came from the US (39%) and the euro area (26%). Our approach is related to the one taken by Blinder (2000).

3 Almost all survey participants (96%) reside in countries with inflation targeting central banks.

4 In the US subsample a discernible minority prefers zero inflation. A few of these respondents explicitly refer to the Friedman rule (Friedman 1969) in written comments.

5 Subsequent questions in the survey corroborate this hypothesis. The important role of central bank credibility also emerges from the results in Ehrmann et al. (2021), who surveyed former ECB Governing Council members focusing on monetary policy communication.

6 Adam et al. (2022) have recently presented a new argument in favor of a positive inflation target based on trends in relative prices.

7 Notwithstanding the current bout of inflation, some observers have not fundamentally changed their views on the secular decline of r* (see, for example, Olivier Blanchard’s interview with Martin Wolf in the Financial Times, 26 May 2022).

8v16% would actually decrease the target and a considerable share (25%) has no opinion.

9 At the time of this writing, sovereign bond markets have become increasingly concerned about fiscal sustainability of highly indebted member states in the euro area as the ECB prepares to raise rates to counter the current bout of inflation. Reichlin et al. (2022) have analysed the ECB’s options.

10vSee Table 5 in Ambrocio et al. (2022). The result is considerably stronger in the euro area sub-sample (available from the authors upon request).

11 Cochrane (2021) presents an alternative explanation based on the fiscal theory of the price level.

* Republished from the original publication on VoxEU in accordance with their copyright rules.