_ George Hawley, associate professor, University of Alabama, research fellow, Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology; Richard Hanania, president, Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology. CSPI, 2020.*

Summary

The data show that most voters who supported Trump were overwhelmingly driven by cultural rather than economic concerns. This implies that the national populist vision is unlikely to provide major electoral gains for the Republican Party. Trump’s popularity among his supporters suffered very little due to his governing mostly as a conventional Republican politician, and those of his party who have adopted more redistributive voting patterns in Congress in recent years have not realized resulting gains at the ballot box. In fact, the American public gave Trump higher marks on the economy than any other major issue, contradicting the claim that more free market economic policies create an electoral cost.

We also note that continuity with previous trends, rather than electoral realignment, was the norm in recent election cycles, meaning that the idea that there has been a major shift towards Republicans becoming the “working class party” is mostly a myth.

Republican success in the future will depend on the party speaking to the cultural, rather than economic, concerns of its voters, whether symbolically or in more tangible terms. This can mean championing issues that Republicans have ignored in recent years like opposition to affirmative action, in addition to facilitating the kind of backlash politics towards cultural liberalism among non-white voters that has worked so well among whites in recent decades. Economic policies that seek to address working-class concerns but hinder overall growth can alienate both voters and donors for little gain.

Introduction

Following President Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential primaries, many voices on the American right began arguing that the Republican Party, and the conservative movement that provides its ideas, had lost their way. Trump handily defeated a large and seemingly formidable field in the primaries, and subsequently defied expectations by triumphing over Hillary Clinton, winning many states long thought to be solidly Democratic. Trump won these victories while rejecting key aspects of the conservative movement’s policy program, especially those related to economics. Trump’s impressive showing among non-Hispanic whites without college degrees provided some credibility to former Trump advisor Steve Bannon’s claim that the 2016 campaign “turned the Republican Party into a working-class party.”1

This led to some soul-searching by conservative intellectuals, journalists, and political leaders. Most leading conservatives were quick to distance themselves from the most lowbrow elements of “Trumpism.” Some, however, also believed that the candidate was tapping into something important that previous Republicans had missed. Perhaps a GOP more invested in alleviating working-class anxieties really could enjoy a major electoral windfall.

After Trump’s victory, as these conservatives sought to reverse engineer an intellectually coherent political philosophy that could provide support for the Trump administration, many focused on economic concerns, concluding that populism represented a viable path forward for the right. One of this report’s co-authors was among the voices claiming that Trump’s victory represented a repudiation of the conservative movement’s economic agenda, and explicitly argued in 2017 that Trump could only be successful if he pursued populist policies.2

With Trump’s loss in 2020, some conservatives may be tempted to view the last four years as an aberration, and conclude that, given the president’s defeat at the ballot box, Trumpism is dead, and the center right can and should return to its previous talking points and policy agenda. Other conservatives, however, remain convinced that there are elements of Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign that remain viable and should be incorporated into a new, forward-thinking agenda for the center right. In particular, they want to revive those aspects of Trump’s successful presidential run that broke with conservative economic orthodoxy. From this perspective, Trump won the 2016 election precisely because of his populist economic agenda: trade protectionism, a promise of new infrastructure projects, and assurances that he would safeguard entitlement programs like Medicare and Social Security. This view also suggests Trump lost his reelection bid because he did not follow through on those promises, but other Republicans could pick up the populist banner and carry it to future victories.3

This new ideology on the right, which some call “national populism,” has many seemingly attractive features. Most notably, it offers the possibility of maintaining the Trump electoral coalition, and perhaps even expanding it, while jettisoning the more controversial and polarizing elements of Trump’s presidency. Some intellectuals and journalists on the political right have always disliked what they see as President Trump’s nativism, bullying, lies, and eagerness to encourage the paranoid fixations and rude behavior of his followers. They did, however, think that the mainstream conservative movement had long been on the wrong track when it came to policy, and believed that Trump’s movement could be a catalyst for readjusting the Republican Party’s domestic policy agenda.

Several important thinkers have sought to create a governing philosophy and policy agenda designed to alleviate middle-America’s many problems. Julius Krein founded the highbrow journal American Affairs, which has published some of the most interesting work of the Trump era. Krein has explicitly stated that he has little interest in culture war issues, and his vision for a populist agenda largely entails technocratic issues such as strengthening the industrial base of the U.S.4 Oren Cass, the founder of American Compass, has been similarly energetic during the Trump years, promoting an industrial policy that goes beyond the conservative movement’s supposed doctrinaire obsession with free markets. Cass is also a long-time political advisor who has worked with Republicans such as Senator Marco Rubio of Florida.5 Other prominent voices have argued that the Democrats have suffered declining support because they abandoned bread-and-butter, working-class economic concerns in favor of boutique identity issues that do not resonate with ordinary voters. Tucker Carlson of Fox News, for example, has made arguments along these lines.6 Senator Josh Hawley has similarly said that the Republican economic agenda must champion the working classes, and break the “arrogant aristocracy” with a hold on both parties.7 Senator Rubio urges fellow Republicans to reject “market fundamentalism” and adopt more populist stances on issues such as trade lest they lose Trump’s voters.8

With the Trump Administration coming to an end after a single term, defeated by a moderate Democrat, the policy agendas for both major parties are up for grabs. More traditional Republicans, who never supported President Trump, view his defeat as a vindication, and believe the Republican Party can return to its previous agenda. Republican supporters of economic populism, on the other hand, can argue that the president’s failure to implement his 2016 campaign promises sunk his reelection prospects. Proponents of both positions have reasonable arguments, and both sides still deserve a fair hearing.

Leaving aside the merits of different economic policy packages, our question is whether any of these arguments are congruent with the public opinion literature and empirical evidence. To learn the answer, we must know whether Trumpism was ever really about economics. We conclude that talk of a Republican populist coalition dominated by working-class voters is premature. The data do not indicate a new class-based electoral realignment. Racial, ethnic, geographic, and religious cleavages in the electorate remain more politically significant than economic divisions.

Economic explanations for Trump’s 2016 victory

After 2016, there were several quantitative studies suggesting there was an economic dimension to Trump’s political success. Most of their conclusions have turned out to be misleading. For example, after analyzing the geographic distribution of Trump’s support in the 2016 Iowa caucuses, Jeff Guo noted in The Washington Post that Trump had stronger support in poorer counties that were losing population. Trump had particularly strong showings in counties where the death rate for middle-aged whites was high.9 After Super Tuesday, Guo showed that this trend was not limited to Iowa. He found the same tendency in all states that provided county-level primary election data. Guo concluded, “We still don’t know what exactly is causing middle-aged white death rates to rise, but it seems that Donald Trump has adeptly channeled this white suffering into political support.”10

Political commentator Andrew Sullivan similarly wrote, after the Republicans seemed to overperform in November’s elections, that while “Trump” was gone, “Trumpism” lived on in the GOP and as a political force.11 According to Charles Murray, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a critic of Trump, economic social trends were a main cause of Trump’s unexpected rise. He suggested that while racism and xenophobia may have motivated many Trump voters, this was not the entire story:

But the central truth of Trumpism as a phenomenon is that the entire American working class has legitimate reasons to be angry at the ruling class. During the past half-century of economic growth, virtually none of the rewards have gone to the working class. The economists can supply caveats and refinements to that statement, but the bottom line is stark: The real family income of people in the bottom half of the income distribution hasn’t increased since the late 1960s.12

This point about stagnating incomes is potentially important. Although many aggregate numbers for the U.S. economy suggest that the nation has been generally well off, other data demonstrate real economic problems. The U.S. economy has grown enormously over recent decades, as has the average productivity of American workers, but that growth has not translated into wages that have kept pace for most Americans.13 Trump’s strong performance among whites without a college degree seems to further reinforce the claim that economic anxiety drove his popularity.

Measuring changes in economic well-being over the course of several decades is challenging, as conclusions will differ according to the measure used.14 Academic debates about how well-off Americans are today compared to the distant past are largely beside the point. Perceptions matter more than objective reality. Regardless of which measure of living standards is most reflective of real economic well-being, large percentages of Americans feel that the days of consistent upward mobility are over. This is especially true for young people. A 2016 poll of Millennials asked whether the “American Dream” was alive or dead for them personally.15 Among Americans between the ages of 18 and 29, 48 percent declared that it was “dead,” including 61 percent of that group that supported Trump.

As further evidence that it was economic anxiety rather than cultural issues driving Trumpism, one could note that Trump’s victory was, in part, explained by new Republican voters who had previously supported Democrats–including President Obama. The fact that these voters had recently voted for the nation’s first African American president provided prima facie evidence that their votes were not predominantly inspired by racial anxieties. Furthermore, in contrast to doomsayers who insisted that Trump’s victory represented a sharp turn toward racial prejudice in the American electorate, polling data indicated that white Americans had been becoming, on average, progressively less prejudiced in the years leading up to 2016.

The triumph of cultural explanations

Since the 2016 election, social scientists have devoted an extraordinary amount of effort towards explaining President Trump’s surprise victory. They have consistently found that racial or cultural explanations for Trump’s win are supported by more evidence than the alternatives.

It is true that white racial attitudes have become more progressive on most issues over the last decade.16 However, the movement has been primarily among white Democrats; although Republicans have not become more progressive, they have not become, on average, more prejudiced.17 The claim that racial attitudes could not have been the motivation of Obama voters that switched to Trump may nonetheless be incorrect. Racial attitudes were just less salient in 2012 than in 2016.18 In other words, the people who switched support from Democrat to Republican did have more conservative racial attitudes than other Democrats in 2012, but those attitudes were less relevant to their vote choice that year. In the 2016 election, racial attitudes were more activated and relevant to vote choice, likely due to Trump’s taking up the immigration issue and running as an unapologetic opponent of political correctness.

Other scholars have thus confirmed that racial and immigration attitudes, rather than economic views, explained some Obama voters backing Trump in 2016.19 Although economic insecurity may have played some role in President Trump’s success, it was a small part of the story; skepticism about large-scale immigration was unquestionably a stronger predictor of support for the president.20 The fact that Trump performed well among whites of lower social status may also be misleading, as this group also had a very low turnout rate in 2016. According to some measures, a majority of Trump’s support came from whites in the class distribution’s top half.21 The question of whether economic anxiety prompted support for Trump is also more complicated than many national populists suggest. Many Trump supporters were primarily motivated by the fear of declining group status resulting from demographic change, rather than more conventional pocketbook concerns.22 The idea that voters supported Trump’s immigration restrictionist agenda for cultural or racial reasons, rather than economic insecurity, is reinforced by similar research on right-wing populism in Europe.23

The data showing that Trump performed especially well in many places suffering economic decline were also correct. However, the fact that poorer counties disproportionately supported Trump is not proof that Trump’s supporters were disproportionately poor. It may be inappropriate to use a single, nationwide measure of income to determine a person’s relative affluence, as different cities, states, and regions vary wildly in their cost of living.24 A six-figure income in San Francisco will lead to a very different standard of living than a similar income in rural Missouri. Although Trump supporters did not tend to be wealthy by national standards in 2016, they were typically the more affluent people living in their ZIP codes. Furthermore, although Trump performed well among the white working class, this was simply a continuation of trends that predated his entry into politics. In other words, this is a group that Republicans have been consolidating for decades.25

There is an additional problem with the claim that Trump’s support was driven by his economic populist promises. As pointed out by Aaron Sibarium, writing for the American Compass, Trump largely failed to implement the policy agenda he promoted during the 2016 campaign, yet most of his voters maintained their high level of support.26 During the first two years of his term, President Trump largely deferred to the Republican-controlled Congress on matters of domestic policy.27 His most significant domestic legislative accomplishment created tax cuts for individuals and corporations that disproportionately favored the rich. The Trump administration supported an attempted rollback of the Affordable Care Act that would have made major cuts in Medicaid, significantly gutting the social safety net without putting forward anything to replace it. These failures to follow through on economic populism did not apparently hinder the president’s approval with his base. Shortly before the 2020 general election, polling indicated that a majority of Americans either strongly or somewhat approved of Trump’s handling of the economy.28 There are many possible explanations for Trump’s loss, but the evidence that his economic policy commitments were the culprit appears weak.

Following the 2020 presidential election, Senator Rubio was repeating what had become a kind of conventional wisdom on the right when he declared that the Republicans could become “a multiethnic, multiracial, working-class party.”29 The 2020 election seemed to show the emergence of new political cleavages because the electorate was less racially polarized than it was in previous presidential elections. President Trump increased his share of the minority vote compared to 2016, but lost support from non-Hispanic whites. Furthermore, as had been the case in 2016, President Trump performed very well among white voters without a college degree, suggesting the generalization of the Republicans as the party of the rich and white was no longer valid. An examination of the 2020 exit polls conducted by CNN, however, does not provide strong evidence of a class-based realignment in voting.30 Trump carried voters without a college degree by only two points. Biden won a majority of the votes from people making less than $100,000 per year; Trump won a majority of those making more. The relationship between income and presidential vote choice furthermore does not appear linear. Biden beat Trump in the lowest income group, but performed slightly better among those making between $50,000 and $100,000 per year.

The biggest divides in vote choice in the U.S. remain between demographic groups not defined exclusively by economics–that is by race, ethnicity, and religion instead, in addition to those of differing cultural attitudes. Whereas 58 percent of non-Hispanic white voters supported Trump in 2020, he only earned 26 percent of the minority vote. Although the latter represents an improvement for Trump compared to 2016, it still indicates high levels of racial polarization in voting. Religion also remains a major cleavage. Sixty percent of Protestants supported Trump, compared to just 31 percent of those with no religious affiliation. Cultural differences therefore remain a crucial fault line in American politics. Furthermore, if there is one party presently situated to be the long-term home of working-class voters, it is the Democrats. We have witnessed some movement in a handful of demographic groups when it comes to vote choice, but for the last several election cycles we have seen more continuity than drastic change.31

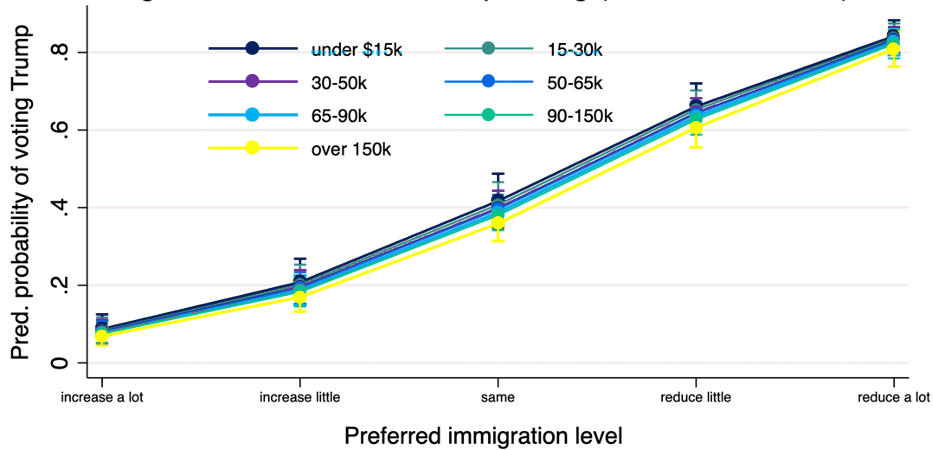

Two figures below show what happens when we compare theories of voting based on socio-economic status to those based on identity and demographic variables in determining support for President Trump.32 Figure 1 shows how the probability of voting Trump in 2016 changed based on income and attitudes towards immigration among white Americans. Among those who were most accepting of immigration, fewer than 10 percent were Trump voters, compared to over 80 percent among whites most opposed to immigration. The impacts of income are barely noticeable in the data.

Figure 1. Immigration attitudes and Trump voting (2016, US whites, ANES)

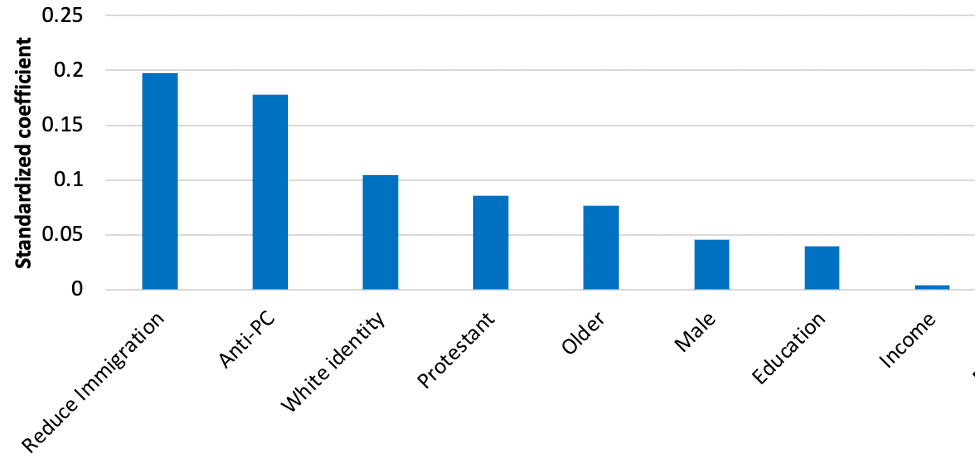

Figure 2 shows how white Americans responded to a question about how warmly they felt about then-candidate Trump, given during the 2016 Republican primaries, based on a regression that included variables related to various attitudes, identity categories, and socio-economic status. As can be seen, cultural attitudes in the form of feelings towards political correctness, immigration, and white identity, have the largest effects. Next come demographic variables, that is, an individual’s sex, age, and religion. Finally, there is education, and then income, which has for all practical purposes zero discernible effect.

Figure 2. Impact on Trump warmth (2016, US whites)

Economic theories of voting

Political scientists have long debated the role of economic evaluations in vote choice and party identification. No scholars question whether economic indicators influence election outcomes–they obviously do. The question is how voters are swayed by macroeconomic conditions and economic policies. Do voters decide based on changes to their own economic circumstances (“pocketbook” or “egotropic” voting),33 or are they looking at the nation’s overall economic trajectory, regardless of their personal financial situation (“sociotropic” voting).34 Are economic voters making decisions based on the most recent economic developments, punishing or rewarding incumbents based on economic performance,35 or are they looking toward the future, voting for the candidate or party they think is most likely to boost the economy?36 Early scholarship on voting and economics assumed that voters were fundamentally self-interested, making decisions according to their own economic portfolios. However, empirical studies of voter behavior have found only modest evidence for this claim.37 It appears that perceptions about the overall health of the economy are stronger predictors of vote choice.

If voters respond to macroeconomic trends, which measures do they use to make their decisions? Income inequality, though an important subject, does not appear to have a strong effect on elections or to be a primary cause of political polarization.38 There is some evidence that inflation can influence election outcomes, but this may vary by which party is in office.39 There is also evidence that unemployment can influence elections, but only Republicans suffer when unemployment is high. In other words, such results are not consistent across studies, and one should not put too much stock in such measures as fundamentally driving election results. The overall level of growth, however, has important consequences for an incumbent’s chances of winning reelection, both in the U.S. and abroad.40

Trump’s strength on the economy in 2020 can be tied to strong fundamentals, with a majority of Americans saying that their economic situation improved under his presidency.41 It is less obvious that specific policies matter, aside from their relationship to subsequent economic developments. Do voters make decisions based on economic policy? There is some debate about whether most issues matter much at all when it comes to vote choice. Most political scientists agree that issues do matter for at least some voters.42 However, voters are also strongly influenced by their partisan identities.43 Partisan attachments have such a strong influence on voters that some will actually change their policy preferences to align them with their party.44 Economic policies, as such, may not have much influence on vote choice.

The degree to which issues shape vote choice is largely dependent upon the degree to which voters know about and understand the issues involved. Some aspects of government are easier for ordinary voters to make sense of than others. When considering the possibility of issue voting, it is important to distinguish between “easy” and “hard” issues.45 Easy issues, the kind that can determine vote choice, are typically symbolic, rather than technical. They are also usually about the ends of a policy, rather than the means. Abortion is an example of an easy issue that can determine vote choice. Desegregation was another, back when it was part of the political debate. Most aspects of economic policy, however, tend to be more complex than the typical voter can follow. They may notice if their tax burden goes down, or if they start benefiting from a new government program. Specific groups with a concentrated interest in a policy debate will notice if they are helped or harmed by policies–farmers are a notable example of this. However, the kinds of technocratic, byzantine policies promoted by the smartest national populists are not likely to garner much interest from the electorate. Their policy proposals may be sound, but they will probably not inspire a mass movement or change electoral outcomes.

This is not to say that politicians can implement any policies they want without fear of reprisals. There is a broad consensus in the American electorate about what kinds of economic policies are acceptable. Among both Republicans and Democrats, there is overwhelming support for a system we can call “welfare capitalism.”46 A typical Republican or Democrat supports a regulated free market, combined with a robust welfare state and longstanding entitlement programs such as Social Security and Medicare. This means that both socialism and economic libertarianism are political non-starters. Within that framework, however, policymakers have a lot of leeway. Voters mostly do not understand the specifics of economic policy, nor are they likely to realize it when a member of Congress breaks with the party line on an issue, and this is even true of voters with above-average levels of political knowledge.47 They are especially unlikely to understand or care about trade policy,48 arguably the national populists’ signature issue. Voters do, however, keep tabs on economic results, and will punish incumbent parties that fail to deliver prosperity.

Do Republican economic moderates perform better?

Proponents of the national populist agenda argue that Republicans have been too dogmatic in their commitment to free-market solutions to economic challenges. Tax cuts and further deregulation may not be the solution to every problem. Here we do not argue the merits of any set of economic policies. We instead want to know if Republicans that break with their party on economic issues enjoy an electoral windfall. To consider this question, we look at the voting records of Republican members of Congress. We then see whether those members that deviate from the party line most frequently enjoy dividends at the ballot box.

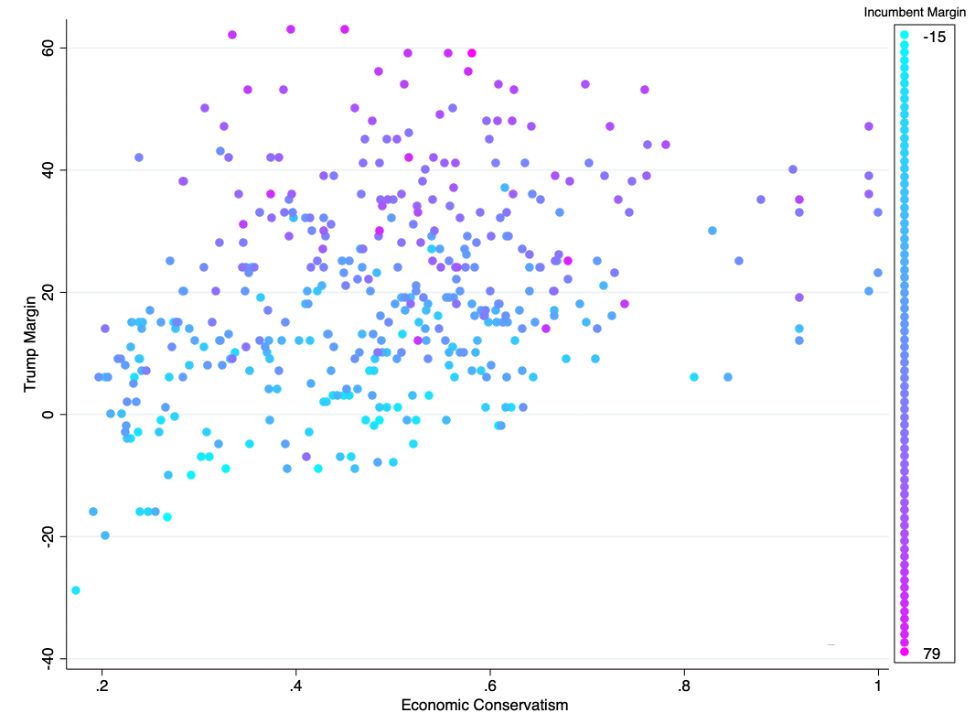

If breaking with GOP orthodoxy was a winning electoral strategy, we would expect Republican politicians who do so to achieve more political success than those who do not in their districts or state. Thus, we carried out a regression in which we investigated whether economic moderation predicts how a Senator or House Representative does in a reelection campaign, controlling for Trump 2016 share in the relevant geographic area (states for senators, districts for House members). Economic ideology is measured by the ideological score of the first dimension of Nokken-Poole in the congressional session before the relevant election, with a higher number indicating more of a free market orientation.49 We carry out this analysis for every Senator and member of Congress who ran for reelection in 2016 or 2018, excluding districts in which there was no GOP incumbent running, where candidates ran unopposed or against a main opponent who was third party, or in which district boundaries were changed. Figure 3 presents a visualization of the data. The x-axis shows the Nokken-Poole first dimension score for each incumbent, and the y-axis shows Trump’s vote share in the matching state or district.50 Color is the incumbent vote share.

Figure 3. Republican incumbent success based on economic ideology score (2016 and 2018)

As can be seen, candidates running in states and districts where Trump did better in 2016 themselves received a higher share of the vote in their reelection bids, which is why the colors of the datapoints are distinct near the top of the graph. The correlation between Trump margin and candidate margin is high, at 0.79 (p < .001). Yet going from left to right shows no relationship between ideological score and incumbent vote share in either direction. In other words, if you know how a district or state voted in the 2016 presidential election, you know something about how well a representative or senator did in a reelection bid in 2016 or 2018. At the same time, knowing how that politician voted on economic issues in the period before the election had no predictive value at all once the Trump 2016 margin was taken into account.

The non-existent link we find between legislator economic ideology and future electoral success is not surprising. The typical American voter possesses limited levels of political knowledge and is not especially ideological.51 We would therefore not expect voters to be aware of how much a particular member of Congress diverges from the party norm. The corollary to this view is that adopting more economically moderate positions is unlikely to have much of an impact for most politicians.

Conclusion

The United States faces several economic challenges in the years ahead. We encourage policy makers to be creative and think beyond twentieth century conservative and liberal talking points and agenda items that may be increasingly anachronistic. However, we also believe in maintaining a sober and dispassionate mindset when considering the political implications of a policy agenda. Based on our analysis of the data and literature, we consider it implausible that the national populist economic agenda, especially one divorced from the “culture war” aspects of Trumpism, can provide a new surge in Republican support in future elections.

Although he lost his reelection bid, President Trump performed unexpectedly well in 2020, given the deadly Covid-19 pandemic that swept the U.S. in the final year of his presidency. Trump lost the popular vote by a significant margin, but he and Joe Biden were extremely close in many important states, putting him within striking distance of another Electoral College victory. Because of the closeness of the race, one can reasonably speculate that, in the absence of the pandemic and the related economic contraction, Trump may have been the favorite in the election, despite failing to live up to his populist promises. It is additionally notable that Republicans further down the ballot performed quite well in 2020. Democrats hoping for a “blue wave” that would reinforce their majority in the House of Representatives, give them firm control of the Senate, and deliver them state legislatures in time for the next round of redistricting, were disappointed. Republicans enjoyed this down-ballot success despite running mostly as conventional conservatives, rather than national populists.

We encourage innovative thinking when it comes to policy, and agree that political parties and politicians should not be bound by ideological shibboleths. While the national populist wing of the conservative movement has exhibited energy and creativity, a major realignment of working-class voters into the Republican ranks is unlikely in the near future, even if the party shifts its economic priorities to the center or left. We furthermore suggest that, when it comes to economics, the most politically advantageous policies for Republicans will be those that result in high levels of growth and low levels of unemployment–whether or not those policies can be reasonably described as “populist.” To the extent that economic policy specifics matter, it would make more sense to advocate simple programs that clearly help people, such as direct payments to families, than more complicated plans that set out to redesign the economy.

For the most part, Republican voters support their party not because of what it can deliver economically, but for cultural reasons. To a large extent, the Republicans may simply benefit from not being Democrats, a party that has moved far to the left in recent years on identity issues.52 One recent study showed white Americans turning against a Democratic candidate in large numbers if she talked about white privilege, with no impact based on whether or not she presented herself as a moderate or more extreme on economic issues.53

Many aspects of the liberal social agenda remain wildly unpopular. Even voters in California rejected affirmative action by a decisive margin in a November referendum, despite Republicans no longer talking about or running on this issue, and the conservative side being significantly outspent.54 Some evidence suggests that the Hispanic shift towards Trump in 2020 may have been driven by resistance among that community to Democratic attitudes towards gender politics. Polls indicated that the “gender gap” in 2020 was larger among Hispanics than any other racial category.55 While a “gender gap” is usually seen as more problematic for the side that is doing worse with women, increasing gender polarization among Latinos worked to Republicans’ advantage in 2020, as any losses among women were more than made up for by gains among men. Analyzing what “went right” with regards to winning over Hispanic men, and to a lesser extent women, can probably give a better guide to future political success than debating the nuances of trade policy.

On the economy, the news for Republicans is more mixed; voters dislike many specific free market policy suggestions, but nonetheless reward politicians for the economic growth that such policies can bring. This implies that Republicans’ electoral success will be determined more by the extent to which they lean in on certain cultural issues than the specifics of economic policy. National populists may still support redistributive policies if they believe it is the right thing to do. Nonetheless, they should do so knowing that it may actually hurt the Republican party in elections if such policies hinder economic growth, alienate donors or distract from the cultural issues they are more likely to win on.

References

1 David Smith, “Steve Bannon: ‘We’ve Turned the Republicans into a Working-Class Party.’” The Guardian. December 17, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/dec/17/steve-bannon-working-class-republicans-labour.

2 George Hawley, “How Trump Can Change Conservatism.” The New York Times. January 19, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/19/opinion/how-donald-trump-can-change-conservatism.html.

3 For one recent example, see “America Has Serious Problems. It’s Time to Stop Blaming Them on ‘Trumpism.’” Quillette. November 9, 2020, https://quillette.com/2020/11/09/america-has-serious-problems-its-time-to-stop-blaming-them-on-trumpism/.

4 Krein stated this explicitly in a recent interview with Ezra Klein, “Trumpism Never Existed. It was always just Trump.” Vox. October 22, 2020, https://www.vox.com/21528267/the-ezra-klein-show-trumpism-donald-trump-joe-biden-2020.

5 James Hohmann, “The Daily 202: Conservative Intellectuals Launch a New Group to Challenge Free-Market ‘Fundamentalism’ on the Right.” The Washington Post. February 18, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/powerpost/paloma/daily-202/2020/02/18/daily-202-conservative-intellectuals-launch-a-new-group-to-challenge-free-market-fundamentalism-on-the-right/5e4b751a602ff12f6a67164b/.

6 This was Carlson’s response to Robin DiAngelo’s best-selling book, White Fragility: “DiAngelo explains at one point, worrying about economic injustice is just another symptom of, brace yourself here, racism, of ‘White Fragility. Get it? Maybe you’re starting to understand why corporate America absolutely loves this book. Why? Because Robin DiAngelo absolves them of their crimes.” Tucker Carlson Tonight, June 24, 2020. http://cpa-connecticut.com/barefootaccountant/tucker-carlson-calls-robin-diangelos-book-white-fragility-an-utterly-ridiculous-book-poisonous-garbage-and-a-crackpot-race-tract/.

7 “Senator Hawley Delivers Maiden Speech in the Senate.” Wednesday, May 15, 2019, https://www.hawley.senate.gov/senator-hawley-delivers-maiden-speech-senate.

8 Alayna Treene. “Rubio Says the GOP Needs to Reset after 2020.” Axios. November 11, 2020, https://www.axios.com/rubio-gop-reset-trump-872340a7-4c75-4c2b-9261-9612c590ee14.html.

9 Jeff Guo, “The Places that Support Trump and Cruz are Suffering. But that’s not True of Rubio.” The Washington Post. February 8, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/02/08/the-places-that-support-trump-and-cruz-are-suffering-but-thats-not-true-of-rubio/.

10 Jeff Guo, “Death Predicts Whether People Vote for Donald Trump.” The Washington Post. March 4, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/03/04/death-predicts-whether-people-vote-for-donald-trump/?tid=sm_tw.

11 Andrew Sullivan, “Trump is Gone. Trumpism Has Arrived.” Substack. November 6, 2020, https://andrewsullivan.substack.com/p/trump-is-gone-trumpism-just-arrived-886.

12 Charles Murray, “Trump’s America.” The Wall Street Journal. February 12, 2016, http://www.wsj.com/articles/donald-trumps-america-1455290458.

13 Josh Bivens and Lawrence Mishel, “Understanding the Historic Divergence Between Productivity and a Typical Worker’s Pay.” Economic Policy Institute. September 2, 2015, http://www.epi.org/publication/understanding-the-historic-divergence-between-productivity-and-a-typical-workers-pay-why-it-matters-and-why-its-real/.

14 Salim Furth, “Stagnant Wages: What the Data Show.” The Heritage Foundation, Backgrounder #3074 on Labor, October 26, 2015, http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2015/10/stagnant-wages-what-the-data-show.

15 Nick Gas, “Poll: Half of Millennials say the American Dream is Dead.” Politico. December 10, 2015, http://www.politico.com/story/2015/12/poll-millennials-american-dream-216632#ixzz417NX31xd.

16 Maria Krysan and Sarah Moberg, “A Portrait of African American and White Racial Attitudes.” University of Illinois Institute of Government and Public Affairs. September 9, 2016, https://igpa.uillinois.edu/sites/igpa.uillinois.edu/files/reports/A-Portrait-of-Racial-Attitudes.pdf; Daniel J. Hopkins and Samantha Washington, “The Rise of Trump, The Fall of Prejudice? Tracking White Americans’ Racial Attitudes Via A Panel Survey, 2008–2018.” Public Opinion Quarterly 84 (2020): 119-140.

17 John Sides, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck, Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018).

18 Ibid.

19 Tyler T. Reny, Loren Collingwood, and Ali A. Valenzuela, “Vote Switching in the 2016 Election: How Racial and Immigration Attitudes, Not Economics, Explain Shifts in White Voting.” Public Opinion Quarterly 83(2019): 91-113.

20 Clifford Young, Katie Ziemer, and Chris Jackson, “Explaining Trump’s Popular Support: Validation of a Nativism Index.” Social Science Quarterly 28(2019): 412-418.

21 Joshua N. Zingher, “On the Measurement of Social Class and Its Role in Shaping White Vote Choice in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election.” Electoral Studies 64 (2020): 102119.

22 Diana C. Mutz, “Status Threat, not Economic Hardship, Explains the 2016 Presidential Vote.” PNAS 115(2018): E4330-E4339

23 Geertje Lucassen, and Marcel Lubbers, “Distinguishing Perceived Cultural and Economic Ethnic Threats.” Comparative Political Studies45(2012): 547-574.

24 Thomas Ogorzalek, Spencer Piston, and Luisa GodinezPuig, “Nationally Poor, Locally Rich: Income and Local Context in the 2016 Presidential Election.” Electoral Studies 67(2020).

25 Nicholas Carnes and Noam Lupu, “The White Working Class and the 2016 Election.” Perspectives on Politics (2020), DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720001267.

26 Aaron Sibarium, “The Limits of the Realignment.” American Compass. November 23, 2020, https://americancompass.org/the-commons/the-limits-of-the-realignment/.

27 For a thorough, behind-the-scenes history of this period, see Tim Alberta, American Carnage: On the Front Lines of the Republican Civil War and the Rise of President Trump (New York: Harper, 2019).

28 The Economist/YouGov Poll, October 41-November 2, 2020, https://docs.cdn.yougov.com/jsojry0vph/econTabReport.pdf.

29 Joseph Choi, “Rubio: GOP Must Rebrand as Party of ‘Multiethnic, Multiracial, Working-Class’ Voters.” The Hill. November 11, 2020, https://thehill.com/homenews/news/525585-rubio-gop-must-rebrand-as-party-of-multiethnic-multiracial-working-class-voters.

30 See Exit Polls, https://www.cnn.com/election/2020/exit-polls/president/national-results.

31 Ezra Klein. Why We’re Polarized (New York: Avid Reader Press, 2020), x-xii.

32 For a fuller explanation of the analyses on which Figure 1 and Figure 2 are based, see Eric Kaufmann, Whiteshift (New York: Abrams Books, 2019): ch. 3.

33 Michael S. Lewis-Beck, “Pocketbook Voting in U.S. National Election Studies: Fact or Artifact?” American Journal of Political Science 29(1985): 348-356.

34 Gerald H. Kramer, “Short‐Term Fluctuations in U.S. Voting Behavior: 1896–1964.” American Political Science Review, 65(1971): 131-143; Gerald H. Kramer, “The Ecological Fallacy Revisited: Aggregate- versus Individual-level Findings on Economics and Elections, and Sociotropic Voting.” American Political Science Review 77(1983): 92-111; Donald R. Kinder and D. Roderick Kiewiet, “Sociotropic Politics: The American Case.” British Journal of Political Science 11(1981): 129-161.

35 Morris Fiorina, Retrospective Voting in American National Elections (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981).

36 Michael B. MacKuen, Robert S. Erikson and James A. Stimson, “Peasants or Bankers? The American Electorate and the U.S. Economy.” American Political Science Review 86(1992): 557-611; Robert S. Erikson, Michael B. MacKuen, and James A. Stimson, “Peasants or Bankers Revisited: Economic Expectations and Presidential Approval.” Electoral Studies 19(2000): 295-312.

37 Stanley Feldman, “Economic Self-Interest and the Vote: Evidence and Meaning.” Political Behavior 6(1984): 229-251; Richard R. Lau, David O. Sears and Tom Jessor, “Fact or Artifact Revisited: Survey Instrument Effects and Pocketbook Politics.” Political Behavior 12(1990): 217-242.

38 Andrew Gelman, Lane Kenworthy, and Yu-Sung Su, “Income Inequality and Partisan Voting in the United States.” Social Science Quarterly91(2020): 1203-1219; Bryan J. Dettrey and James E. Campbell, “Has Growing Income Inequality Polarized the American Electorate? Class, Party, and Ideological Polarization.” Social Science Quarterly 94(2013): 1062-1083.

39 Fredrik Carlsen. “Unemployment, Inflation and Government Popularity — Are there Partisan Effects?” Electoral Studies 19(2000): 141-150.

40 Campello, Daniela, and Cesar Zucco Jr., “Presidential Success and the World Economy.” Journal of Politics 78(2016): 589-602.

41 Aaron Blake, “Trump’s Under-Performing 2020 Campaign, in 2 Key Numbers.” Washington Post. October 22, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/10/22/trump-better-off-than-four-years-ago-question/.

42 Stephen Ansolabehere, Jonathan Rodden and James M. Snyder, Jr., “The Strength of Issues: Using Multiple Measures to Gauge Preference Stability, Ideological Constraint, and Issue Voting.” American Political Science Review 102(2008): 215-232; Stephen A. Jessee, “Partisan Bias, Political Information and Spatial Voting in the 2008 Presidential Election.” Journal of Politics 72(2010): 327-340.

43 Donald Green, Bradley Palmquist, and Eric Schickley, Partisan Hearts and Minds: Political Parties and the Social Identities of Voters (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press).

44 Gabriel S. Lenz, Follow the Leader? How Voters Respond to Politicians’ Policies and Performance (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2012).

45 Edward G. Carmines and James A. Stimson, “The Two Faces of Issue Voting.” American Political Science Review 74(1980): 78-91.

46 Stephen Miller, “Conservatives and Liberals on Economics: Expected Differences, Surprising Similarities.” Critical Review 19(2007): 47-64.

47 Logan Dancey and Geoffrey Sheagley, “Heuristics Behaving Badly: Party Cues and Voter Knowledge.” American Journal of Political Science57(2013): 312-325.

48 Alexandra Guisinger, “Determining Trade Policy: Do Voters Hold Politicians Accountable?” International Organization 63(2009): 533-557.

49 Nokken, Timothy P., and Keith T. Poole, “Congressional Party Defection in American History.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 29(2004): 545-568.

50 Ibid.

51 Donald R. Kinder and Nathan P. Kalmoe, Neither Liberal nor Conservative: Ideological Innocence in the American Public (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

52 Zach Goldberg, “How the Media Led the Great Racial Awokening.” Tablet. August 4, 2020, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/media-great-racial-awakening.

53 Richard Hanania, George Hawley, and Eric Kaufmann. “Losing Elections, Winning the Debate: Progressive Racial Rhetoric and White Backlash.” PsyArXiv (2020), https://psyarxiv.com/uzkvf/.

54 Janie Har, “Political Liberal California Rejects Affirmative Action.” Associated Press, November 4, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/race-and-ethnicity-campaigns-san-francisco-college-admissions-california-4c56c600c86f37289e435be85695872a.

55 David Leonhardt, “The Latino Gender Gap.” New York Times. October 22, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/22/briefing/popp-francis-russia-iran-purdue.html.

* Republished with the kind permission of the author from the original publication on the Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology.

** Image citation: PragerU.