_ Andreas Diemer, postdoctoral researcher, Swedish Institute for Social Research, Stockholm University; Simona Iammarino, professor, Department of Geography & Environment, LSE; Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, Princesa de Asturias chair, professor, London School of Economics; Research Fellow, CEPR; Michael Storper, professor of, LSE; distinguished professor of Regional and International Development in Urban Planning; UCLA. VoxEU, 24 July 2022.

Many regions in Europe are stuck in a development trap and face significant structural challenges in retrieving past dynamism or improving prosperity for their residents. This analytical note conceptualises what constitutes a development trap at a regional level in Europe and identifies which regions have been trapped or at risk of becoming trapped in recent years. Regional development traps can arise at many different levels of income. Springing these traps would improve overall European competitiveness and help quell the discontent and resentment of citizens living in these areas.

…

Long-term regional economic stagnation at varying levels of development is becoming the norm across many parts of Europe (European Commission 2017, 2022). Subpar economic performance, lack of employment opportunities, and loss of competitiveness are causing social and political resentment towards what is increasingly regarded – justly or unjustly – as a system that does not benefit areas that are being left behind (Dijkstra et al. 2020). Regional stagnation is also fuelling the perception that there is a two-tier Europe, divided between a reduced number of dynamic and competitive super-regions, in which economic and political power combine, and ever-growing ranks of left-behind places, increasingly perceived as not mattering or mattering much less than they once did (McCann 2020, McCann and Ortega-Argilés 2021, Rodríguez-Pose 2018).

Stagnation has received some attention at the international scale in the guise of the ‘middle-income trap’. But stagnating regions have not received consistent policy scrutiny thus far, in part because the problem of stagnation has not been precisely defined and analysed at the subnational scale, and because some stagnating regions do so at relatively high-income levels. As a consequence, in Europe, the plights of such regions have fallen in between the cracks of a European policy mostly geared towards the least developed regions and national policies that have tended to reinforce the winning areas.

Defining and measuring regional development traps in Europe

In a recent article (Diemer et al. 2022), we address these gaps in existing knowledge by introducing and operationalising the concept of the regional development trap in Europe. This concept borrows from the theory of middle-income-trapped countries (Eichengreen et al. 2012, Kharas and Kohli 2011) but rethinks it to reflect specificities of regional development trajectories in economies with a long tradition of industrialisation.

We define the regional development trap as the state of a region unable to retain its economic dynamism in terms of income, productivity, and employment, while also underperforming its national and European peers on these same dimensions. Stated differently, a region is in a development trap if the prosperity of its residents does not improve relative to its past performance and the prevailing economic conditions in national and European markets. We apply this concept to regions that fall into this state from different starting levels of economic development relative to the European distribution, distinguishing between regional development traps at high, middle, and low levels of income.

We measure development traps along a three-dimensional continuum, including GDP per capita, productivity, and employment. In line with the literature on growth slowdowns (Hausmann et al. 2005), the focus is on growth rates in these variables, comparing the relative performance of a region to three benchmarks: the region itself in its immediate past, other regions in their respective countries, and the rest of Europe. We then develop a synthetic index of dynamism to map the regions in Europe that have been trapped or were at risk of falling into a development trap.

A portrait of regional development traps in Europe

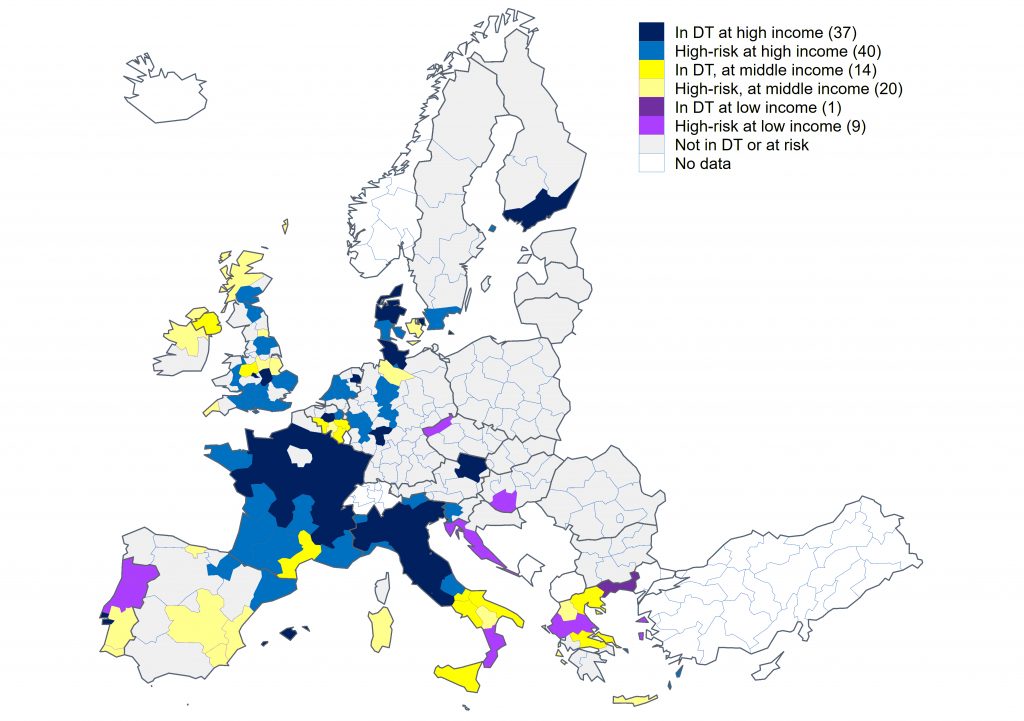

Figure 1 maps average scores of the development-trap measure over 2001–15. Only regions in the top two quartiles of risk are mapped, with quartile values computed using the distribution of the index values over 1990–2015, to benchmark risk levels across all possible historic values.

Figure 1. Risk of being trapped (2001–15) by initial levels of development

Regions in darker shades are those that, on average, can be considered to be in a development trap; those in lighter shades are at high risk of becoming trapped. The colour coding allows us to distinguish between development traps at high levels of income (in blue), at middle-income level (in yellow), and at low-income level (in red), depending on whether the initial regional GDP per capita was above the EU average, between 75 and 100 percent of it, or below 75 percent of the EU average. This three-way categorisation visually highlights the different types of regional traps across Europe: decline, stagnation, and persistent backwardness.

The map shows several regions considered to be in or close to the European core – often those at the heart of the so-called ‘blue banana’ – which are stagnating. The highest level of entrapment is found among ‘industrial losers’ (Rosés and Wolf 2018) in France, particularly in the areas surrounding Paris, and in Northern Italy.

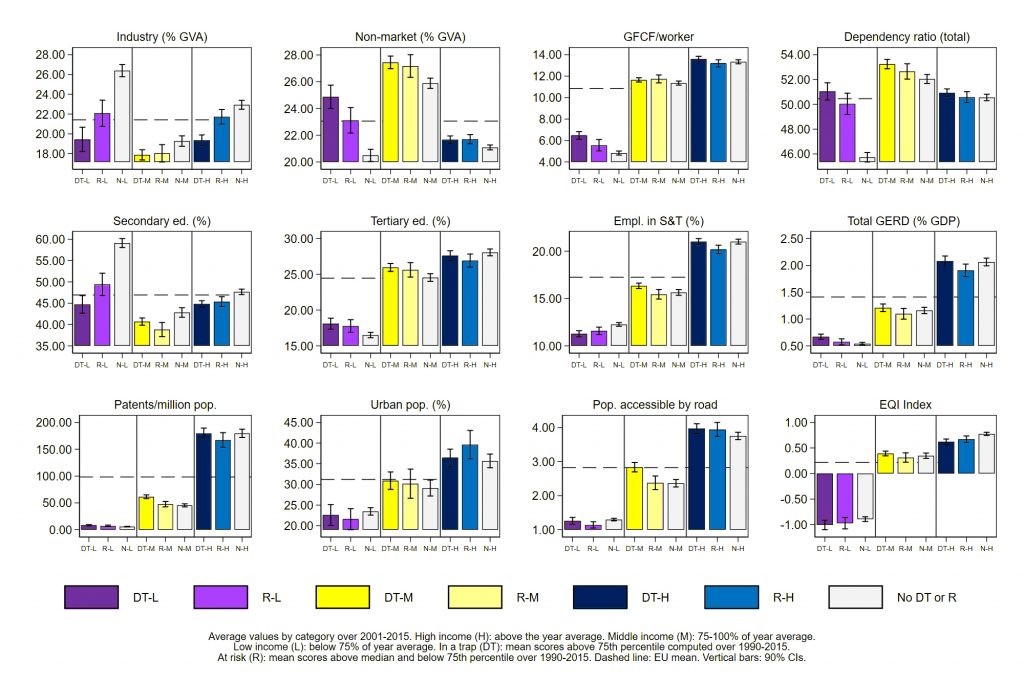

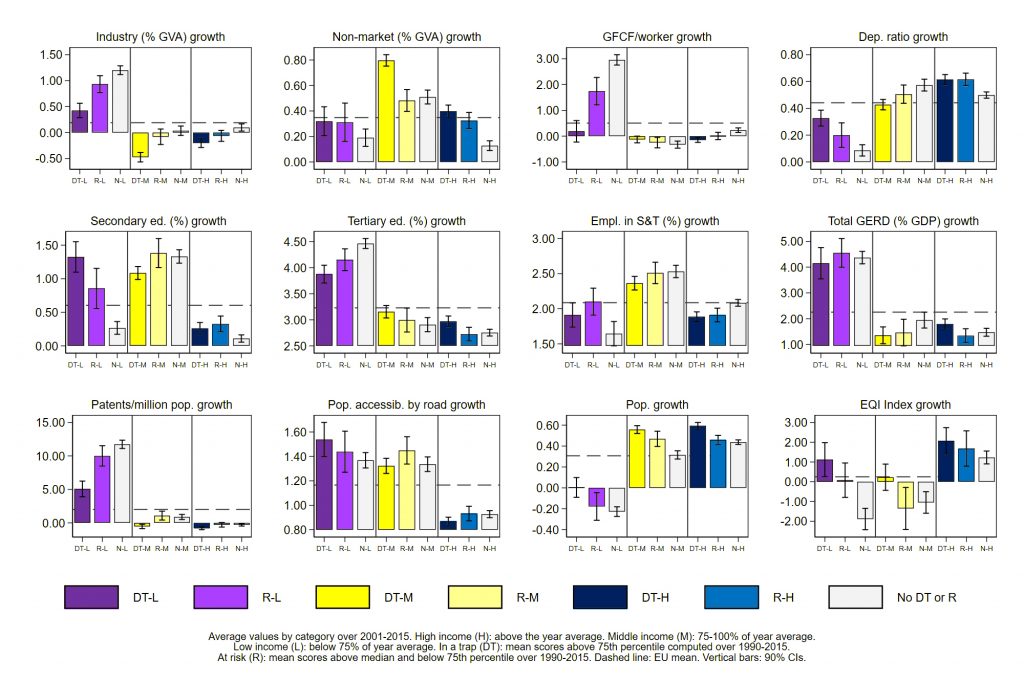

Using categories (and a colouring scheme) consistent with those of Figure 1, the characteristics of regions in or at risk of being in a development trap can be compared to regions that are not. We compare them across a range of features related to economic structure, physical capital and infrastructure, human capital and labour force characteristics, economic geography, and institutional quality. Figure 2 shows average characteristics by group in levels; Figure 3 considers them in changes.

Figure 2. Characteristics of trapped regions by income group levels

Figure 3. Evolution of trapped regions by income group levels

A few features stand out. Regions in a development trap, or at risk of being trapped, display lower shares of manufacturing industry and higher shares of non-market services (mainly covering public services in the areas of social welfare, health, education, and defence), relative to other non-trapped regions at comparable levels of development. Regions in a trap or at risk of being trapped also show lower levels of secondary education attainment among the working-age population and higher age dependency ratios. Institutional quality is linked with relatively lower development-trap scores in low- and high-income regions.

Industry growth is lowest (or even negative) among regions that are trapped or at risk of being trapped. Moreover, being trapped is linked with growth in non-market services. Low-income trapped areas also show weaker growth in shares of college-educated inhabitants, although this group expands faster overall (due to its starting at lower levels). Trapped regions consistently display the weakest growth in patents per capita. In poorer areas, dynamic regions have strong increases in their outputs, highlighting the potentially important role played by innovation in achieving regional dynamism.

Trapped regions deserve policy attention

Identifying trapped regions shows a Europe of different speeds. Entrapment is causing social and political resentment toward what is increasingly regarded – justly or unjustly – as a system that does not help areas being left behind (Dijkstra et al. 2020). This fuels the perception that there is a two-tier Europe, divided between a relatively small number of dynamic and competitive super-regions that cumulate economic, political, and social power and prestige, and ever-growing ranks of left-behind places, whose residents feel they matter less and less (McCann 2020, McCann and Ortega-Argilés 2021, Rodríguez-Pose 2018, Guiso et al. 2018). The analysis of development traps makes these places visible.

The problems linked to economically trapped regions have been mostly neglected by European and national decision makers, who historically have tended to target least-advanced regions or focused on reinforcing winners in dynamic urban agglomerations. Caught between these two priorities, many trapped regions have struggled to attract interest.

The challenge for policymakers is to add development traps to their portfolio of concerns, in the many and varied circumstances that these exist in Europe. This problem warrants attention not just ex post, when stagnation is entrenched, but also when looking forward. Identifying regions in a development trap sounds the alarm bell on these surprisingly widespread risks in Europe.

References

Diemer, A, S Iammarino, A Rodriguez-Pose and M Storper (2022), “The regional development trap in Europe”, Economic Geography.

Dijkstra, L, H Poelman and A Rodríguez-Pose (2020), “The geography of EU discontent”, Regional Studies 54(6): 737–53.

Eichengreen, B, D Park and K Shin (2012), “When fast-growing economies slow down: International evidence and implications for China”, Asian Economic Papers 11(1): 42–87.

European Commission (2017), My region, my Europe, our future: Seventh report on economic, social and territorial cohesion, L Dijkstra (ed.), European Commission, Directorate General for Regional and Urban Policy.

European Commission (2022), Cohesion in Europe towards 2050: Eight report on economic, social and territorial cohesion, L Dijkstra (ed.), European Commission, Directorate General for Regional and Urban Policy.

Guiso, L, H Herrera, M Morelli and T Sonno (2018), “The populism backlash: An economically driven backlash”, VoxEU.org, 18 March.

Hausmann, R, L Pritchett and D Rodrik (2005), “Growth accelerations”, Journal of Economic Growth 10(4): 303–29.

Kharas, H, and H Kohli (2011), “What is the middle income trap, why do countries fall into it, and how can it be avoided?”, Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies 3(3): 281–89.

McCann, P (2020), “Perceptions of regional inequality and the geography of discontent: Insights from the UK”, Regional Studies 54(2): 256–67.

McCann, P, and R Ortega-Argilés (2021), “The UK ‘geography of discontent’: Narratives, Brexit and inter-regional ‘levelling up’”, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 14(3): 545–64.

Rodríguez-Pose, A (2018), “The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it)”, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11(1): 189–209.

Rosés, J R, and N Wolf (2018), “The return of regional inequality: Europe from 1900 to today”, VoxEU.org, 14 March.

* Republished from the original publication on VoxEU in accordance with their copyright rules.