_ Philipp Heimberger, Economist, wiiw; Nikolaus Kowall, Endowed Professor for International Macroeconomics, University of Economics, Management and Finance. Vienna, 24 July 2020. Published for debate.

Recent policy debates concerning the EU recovery fund and public debt have strongly focused on Italy and kept reinforcing stereotypes on the country’s economic governance.

‘A country cannot permanently live beyond its means. The Italian state must urgently tighten its belt!’ Politicians and journalists have been repeating variations of this statement again and again when it comes to discussing Italy and its economy. Last year, we heard that Italy must stop being ‘profligate’ when the European Commission and political leaders of several EU member states were pushing for opening an excessive deficit procedure against Italy. Since the start of the Corona crisis, several political leaders have again lamented that Italy has allegedly failed to conduct proper ‘structural reforms’. Concerning negotiations on the EU recovery fund, leading politicians and media questioned whether Italy should receive financial support.

But all of the above is based on distorted pictures of Italy. To see why, consider the following facts.

More ‘frugal’ than any other EU country

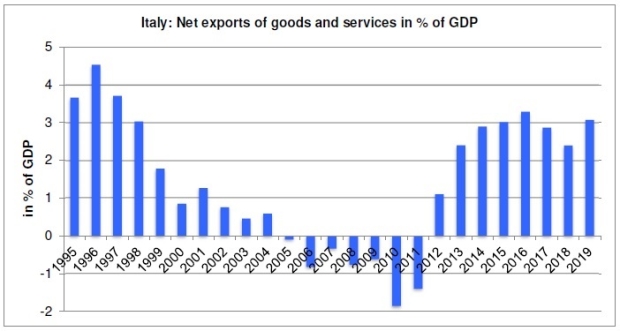

First, Italy has not been living beyond its means. Since 2012, Italy has consistently recorded export surpluses. In other words: the Italian economy consumes less than it produces – if anything, it lives below its means.

Source: AMECO (Spring 2020); own calculations.

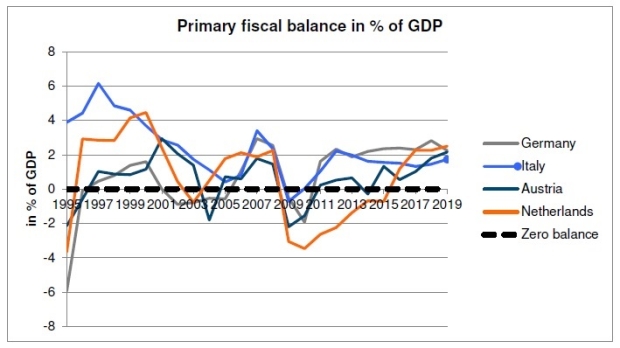

Second, high Italian public debt is primarily a legacy from the 1980s. Since then, Italy has been more ‘frugal’ than any other EU country. From 1992 onwards, the Italian state has consistently recorded primary budget surpluses, which exclude interest payments. Italy did more fiscal consolidation than Germany and the ‘frugal four’ (Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden).

Source: AMECO (Spring 2020); own calculations.

Italy’s government debt of 135% of GDP is striking only because its economic growth has been so weak over the last twenty years. Rather than reducing the public-debt-to-GDP ratio, austere policies have contributed to economic stagnation so that the Italian state was unable to ‘grow out’ of the existing debt.

Third, Italian governments have diligently followed European requirements for liberalising its labour market. In 2014, Matteo Renzi’s government reduced workers’ dismissal protection, which can be seen as a continuation of the process of labour market liberalisation that started in the 1990s. These ‘structural reforms’ did not only reduce inflation and real wages. They also pushed down unemployment by generating temporary jobs: the unemployment rate in Italy was lower than in Germany and France when the financial crisis hit in 2008. However, cheap labour diminished incentives for Italian companies to make labour-saving investments – with negative effects on productivity, which is the basis for long-term growth.

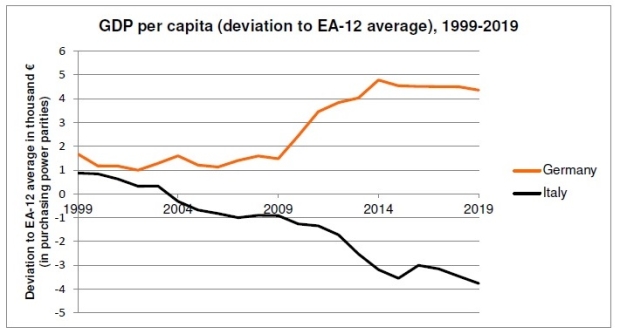

Fourth, Italy’s average standard of living was virtually the same as in Germany twenty years ago. However, Italy has fallen behind since the introduction of the euro. By 2019, Italian per capita income was more than 20% below that of Germany. Nevertheless, Italy still records the second-largest share in the EU’s industrial production behind Germany – and has been a net contributor to the EU budget.

Data: Eurostat; own calculations. Euro area average (EA-12) includes the following countries: Austria, Belgium, Germany, Spain, Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal.

Decades of tight fiscal policy

Recent developments in Italian political economy – including corruption and organised crime – should not be neglected. But it should also be remembered that Italy has never been a haven of political stability. In fact, the current government is the 66th cabinet since World War II. The mafia and corruption have always existed over the past decades. But this did not hinder the Italian economy from developing quite dynamically in the Post-World War II era running up to Italy’s membership in the euro area.

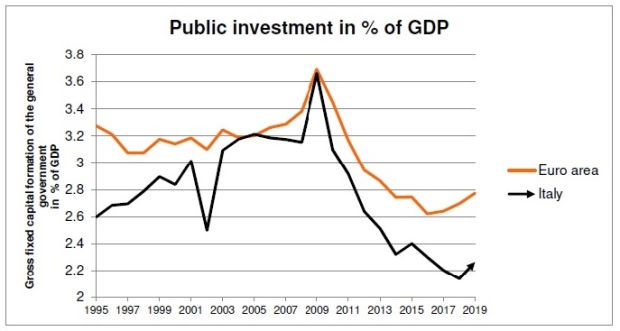

Italy’s persistent aggregate demand and productivity misery is partly a consequence of the shortcomings of the institutions and rules in the euro area. While Italy has not been able to pursue a tailor-made monetary and exchange rate policy to support economic development since joining the euro, the restrictive austerity and reform requirements by the European Commission (and the ECB) have also systematically tied the hands of national fiscal policymakers in the years before the Corona crisis. Decades of tight fiscal policy have deprived the Italian health sector of capacity to offer adequate protection for the Italian population during the COVID-19 crisis. Public investment in Italy has fallen victim to fiscal austerity. Over the last ten years, Italian public investment has been cut more strongly than the Eurozone average – with negative short-term and long-term growth effects.

Source: AMECO (Spring 2020).

The EU recovery fund negotiations

In the aftermath of the Corona crisis, European policy makers should avoid repeating the mistake of pushing the Italian government towards fiscal austerity and structural reforms from the market-liberal playbook. A more promising policy approach would be to go for an investment strategy – the start of which could be made by using money from the EU recovery fund – and modern European industrial policies to provide a short and long run boost to economic activity.

In the negotiations on the EU recovery fund, the German government finally understood the urgent need for investment; it promoted a common ‘recovery plan’ with French president Macron. Have the Germans become altruistic? No, they just know that half of their exports go to the EU. They understand that the growth of the world economy has slowed down, and that we may soon see tendencies towards trade de-globalisation and so the importance of the EU’s internal market can be expected to grow.

Alert minds also see the political dimension. Low levels of solidarity with Italy at the start of the COVID‑19 pandemic were politically not very helpful: according to an April survey, almost half of Italians see Germany as an ‘enemy country’, followed by France (38%). ‘Friendly countries’ in the eyes of the majority are now China (52%) and Russia (32%). Troll factories in the US and in Russia exacerbate such intra-European tensions. If policymakers fail to address rising discontent among the European population, the breeding ground for nationalist and anti-democratic tendencies will continue to flourish.

There are fears that the use of distorted pictures by leaders of the so-called “frugal” states in negotiations on the EU recovery fund may leave permanent scars on voters in countries such as Italy. Upholding distorted pictures of the Italian economy would be poisonous and push into the hands of right-wing populists who want Italy to leave the European Union.

If Italy were to seek ‘Italexit’ after a possible right-wing populist election victory in the near future, the consequences for other countries would be fatal. Economically, the break-up of the euro area would above all strongly damage the industrial basis of export-dependent growth models in countries such as Germany, Austria and the Netherlands due to likely revaluations of their currencies. Politically, it would be the end of the decades-long process of European integration.

Source: https://wiiw.ac.at/