_ Prof. Dr. Fritz Söllner, Institute for Economics, Department of Public Finance, Ilmenau University of Technology. Statement on the motion of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group “Fighting price increases – protective shield against inflation” for the public hearing in the Finance Committee of the German Bundestag. Berlin, September 11, 2022.

1. The crisis and its causes

The current critical development in Germany has various causes, the symptoms of which partially overlap. When diagnosing the problem, a precise distinction must be made between these causes, since an effective and efficient crisis policy can only be designed if this is the case. Cum grano salis, two main causes can be identified: the monetary policy of the ECB, which is responsible for inflation in general; and the sanctions and countersanctions imposed in the wake of the Russian attack on Ukraine, which have led to energy shortages and threats to energy security. Both causes interact in the most serious symptom of the current crisis: the sharp rise in energy prices.

2. Inflation and the monetary policy of the ECB

“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.”

– Milton Friedman, 1963.

The main reason for the current inflationary development is the monetary policy of the ECB. The purchases of government bonds, which began in the wake of the euro crisis and were intensified significantly as a result of the corona crisis, have led to an excessive increase in the central bank money supply (compared to the growth in real gross domestic product).[1]

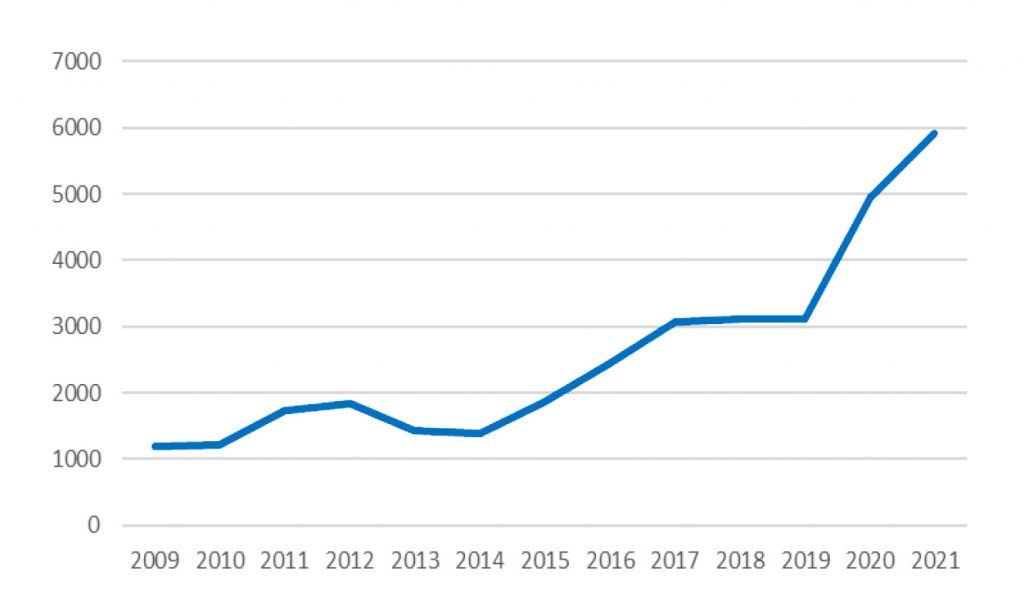

The central bank money supply grew by 392.1 percent from December 31, 2009 to December 31, 2021 (Fig. 1), while real gross domestic product in the euro zone increased by only 15.6 percent in the same period (Eurostat 2022).

Fig. 1. Central bank money stock of the ECB (2009-2021, in billion euros)

Source: ECB, Consolidated Balance Sheet of the Eurosystem, various editions.

In view of this, the outbreak of inflation was only a matter of time. Asset price developments have been showing inflationary tendencies for a long time, and the rise in consumer goods prices, the index for which serves as a benchmark for monetary stability, has already accelerated in 2021, i.e., before the outbreak of the Ukraine war. The war in Ukraine and the delivery bottlenecks in the wake of the corona crisis may have accelerated the depreciation of money, perhaps even triggered it – but it was caused by the monetary policy of the ECB. Disregarding its main objective of price stability and disregarding the prohibition of monetary state financing, the ECB financed excessive budget deficits (and indirectly also the trade balance deficits) of various euro countries through printing money. Thus, it pursued fiscal policy with the means of monetary policy.[2]

We are now witnessing the inevitable consequences of this policy in the form of the current inflation, which will most likely accelerate and most likely last longer. This development could only be stopped by decisive monetary policy countermeasures, which include, in particular, the rapid and significant reduction in the holdings of government bonds in the ECB’s portfolio. In this way, the central bank money supply could be reduced again before it is further reflected in a growing total money supply – and thus further in rising prices. The ECB seems to lack the will to do this; it is evidently not pursuing the goal of combatting inflation so much as the goal of not jeopardizing the financing conditions of certain euro countries. The rate hikes that have already been taken and are still being announced are only of a cosmetic nature in view of the dramatic situation and are also counteracted by the creation of the so-called “Transmission Protection Instrument” (TPI), with which the ECB reserves the right to purchase further government bonds. The CDU/CSU’s motion therefore rightly states that “the current ECB policy is not appropriate to the situation”. However, this judgment applies not only to the present but to the entire last decade.

A “protective shield against inflation”, as called for in the motion, is not possible. Without vigorous monetary policy countermeasures from the ECB, inflation will take its course. It cannot be stopped by fiscal policy or other measures at the level of the euro countries. At best, one can try to compensate for their consequences in individual areas where they are particularly serious (see Part 4).

3. The energy crisis: background, consequences and options for action

The current energy crisis in Germany and Europe would not have been possible without the energy policy of the past 20 years. This energy policy has focused on climate protection and the “energy transition” while neglecting the goals of economy and security of supply. The Bundesrechnungshof (Federal Audit Office) in particular has drawn attention to this and the associated dangers several times in special reports (cf., e.g., Bundesrechnungshof 2021), but unfortunately these warnings were ignored. With the near-complete phase-out of nuclear power and the phase-out of coal power in full swing, base load is mainly covered by natural gas. The government relied on Russia for the supply of this energy source. There were good reasons for this, such as the relatively low prices and previous experience with Russia as a reliable supplier. But in this way, the country has become dependent on Russia because a substitution of Russian gas deliveries by deliveries from other countries or even by other energy sources is only possible to a very limited extent in the short term and at best at significantly higher prices (Pittel et al. 2022, 5-6).

That is why the EU sanctions and Russia’s countermeasures are having the serious consequences that we can see in Germany at the moment and that we must expect in the near future.

Above all, there has been an enormous increase in the price of gas, as well as a significant increase in the price of oil and, as a result of this development, an increase in the price of electricity. Consumers and the economy have already reacted to this with a drop in demand, but the potential for savings by raising “efficiency reserves” or giving up “unnecessary” energy consumption is limited (Pittel et al. 2022, 4-5). In fact, much of the savings have come from production cuts or shutdowns. BDI President Russwurm pointed out on August 31, 2022 that the industry had consumed 21 percent less gas in the course of 2022 than in the same period of the previous year, but that this was not a success, but “an expression of a massive problem”. “The substance of the industry is threatened” (quoted from Vahrenholt 2022). In addition to aluminium production, the manufacture of fertilizers and other chemical products is particularly affected.

The terms of trade have deteriorated significantly as a result of the increased prices for energy imports (Deutsche Bundesbank 2022, 28; Statistisches Bundesamt 2022).[3] This means that the real value of goods that Germany can import for a certain amount of export goods has fallen. This is accompanied by heavy losses in real income for the German economy, which will wipe out a large part of the growth actually expected for 2022. Under optimistic assumptions, growth in real gross domestic product of 1.9 percent (2.4 percent) can still be expected for 2022 (2023), which represents a drop in growth of 2.3 (0.8) percentage points compared to the economic forecasts from December 2021 (Deutsche Bundesbank 2022, 17). But it could also get worse: Should Russia completely stop its energy exports to the EU, energy rationing and further production declines would be unavoidable. As a result, growth in 2022 would drop to just 0.5 percent and in 2023 there would be a recession with real gross domestic product falling by 3.2 percent (Deutsche Bundesbank 2022, 43).

These losses in growth and falls in real income are caused by supply-side, exogenous shocks. They can therefore not be compensated for by demand-side economic policy measures. A »relief«, which is always talked about so much, is not possible on a macroeconomic level. At best, it is possible to redistribute the unavoidable burden on the German economy in one way or another. Relief of certain economic subjects therefore leads to burdens on other economic subjects – with the latter possibly belonging to future generations. Quite apart from that, all such measures are always associated with additional costs that further burden the economy as a whole (see Part 4).

Against the background of the current situation, there are essentially two policy options: First, sanctions against Russia could be lifted. With a probability bordering on certainty, Russia would then also end its countermeasures: gas supplies would be resumed in full; oil and gas prices would fall significantly; the terms of trade would improve again; a recession would no longer threaten; on the contrary, there would be a surge in growth. Second, sanctions could be maintained (or even tightened). Then we will face the consequences described above with all the disadvantages for the German economy and German citizens.

The decision between these two options is not an economic one, but a political one. If this decision is made in favour of the second alternative and if one continues to pursue the previous policy, then on the one hand the unavoidable economic consequences of this policy should be communicated clearly and openly and, in particular, one should not pretend that the state can relieve the citizens from the consequences completely or even for the most part by “reducing the burden”.

On the other hand, measures should be taken so that at least the economic damage that can be avoided will be avoided. In view of the shortage of gas and the threat of gas rationing, this energy source should be used as far as possible in those applications in which substitution is not possible in the medium term – i.e., for heating buildings and for process heat in industry. In order to prevent power bottlenecks and counteract rising electricity prices, the other two energy sources that can provide base loads, i.e., coal and nuclear energy, must be used more intensively and for longer than previously intended. Calculations show that with the operation of six nuclear power plants and the revitalization of the lignite-fired power plants, electricity costs would be more than halved, namely from 370 euros per MWh to 170 euros per MWh (Vahrenholt 2022).

Only in this way, i.e., by expanding the supply, can the “price pressure on energy products” be reduced in the current situation, as demanded by the CDU/CSU. Direct price interventions, in particular price caps of any kind fixed by the state, are in no way suitable for this purpose. These impair the signalling and allocation function of the price system and only lead to aggravation of the problems. Artificially low prices are of little use if there is excess demand at these prices and if therefore rationing measures with all their consequences have to be taken.

For this reason, the intended, but not yet known in detail, skimming off of so-called “windfall profits” from the electricity providers should also be viewed critically. Electricity pricing according to the merit order principle is not responsible for the emergence of these profits, as is sometimes claimed. This price formation mechanism corresponds to the normal market price mechanism, in which the marginal supplier also “determines” the equilibrium price. Rather, the problem is that the supply curve has shifted to the left and steepened at the same time. In combination with relatively inelastic demand, this leads to rising producer surpluses. The only way to remedy this in the long run is to “normalize” the supply function, which would require a U-turn in energy policy in the current situation. In contrast, a “skimming off of windfall profits” would only represent a cure for the symptoms. It would also have the disadvantage that (depending on how it is designed) it acts like a price cap on the supply side, which can lead to negative supply reactions: namely the withdrawal of suppliers who produce at costs that are higher than the price from which the “windfall profits” are to be skimmed off.[4]

In addition to these supply-side measures, demand-side measures may also be indicated for socio-political reasons. These, inter alia, I would like to address in the following section.

4. Demand-side and complementary supply-side measures

In its motion, the CDU/CSU parliamentary group calls for various measures, some of which are on the demand side and some on the supply side, on which I would like to comment below. However, I will deal with the first measure, the “neutralization” of cold progression, in a separate section because of its fundamental importance.

It certainly makes sense and is necessary from a socio-political point of view “to lower the price pressure on energy products”. Fortunately, no direct interventions in the price mechanism are suggested, which experience has shown to do more harm than good. Rather, tax cuts and transfer payments are intended to serve this purpose. The latter are most suitable for “tailor-made” relief, whereas the relief effect of tax cuts is certainly welcome by all citizens, but is not limited to cases of hardship. In connection with energy taxation, one could (and should) discuss whether the energy tax on fossil fuels is still justified at all in view of the CO2 tax levied at the same time. The adjustment of the commuter subsidy to the actual development of motor vehicle and especially fuel costs is a requirement of tax justice and should actually be a matter of course. One should not speak of a “relief” in the sense meant here.

The “additional structural measures”, as argued for in the motion, may well make sense, but in the short term they will hardly be able to contribute anything to overcoming the crisis.

The same applies to the implementation of “trade agreements that have already been negotiated” and the conclusion of new trade agreements. In the medium term at best, this will lead to an expansion of supply and to price reductions. It must also be taken into account that while this relieves citizens in their role as consumers, some citizens will also be burdened in their role as providers of factors of production – insofar as they are used to produce goods that will be substituted by the additional imports.

The renunciation of “the planned set-aside of 4 percent of the arable land” of the EU Green Deal seems absolutely necessary in the current situation. But even in this case one shouldn’t expect too much of an effect.

There are calls for waiving or at least postponing legislative projects at the European level “that lead to further burdens through political regulation”. This demand is to be welcomed unreservedly and should be pursued independently of this crisis or other crises. After all, projects that lead to “burdens” on balance cannot be justified from an economic point of view, especially from the point of view of cost-benefit analysis.

Greater budgetary discipline and solid state financing would be desirable at both the national and the European level for a variety of reasons. However, it will probably remain wishful thinking. Adherence to the debt brake from 2023 onwards seems rather unlikely in view of the costly projects already planned or required and, above all, the considerable economic risks; at least this applies to 2023. It may be pointed out that the implementation of the tax cuts and transfer payments demanded by the CDU/CSU would not make it easier to comply with the debt brake in the future. In the current situation and in view of the high budget deficits in many countries, the EU Stability and Growth Pact is unlikely to be paid attention to again in the foreseeable future.

5. The “cold progression” and the measures to avoid it

Just like the adjustment of the commuter subsidy, the “neutralization” of the cold progression is a question of tax justice and not of crisis policy.

If, for example, nominal income rises as a result of inflation, but real income remains the same, then the progressive income tax rate with its nominal tax base leads to the average tax rate of taxpayers increasing, although their ability to pay, which is measured by real income, has remained the same.[5] This phenomenon is called cold progression.

The prevention or elimination of the cold progression is a requirement of tax justice, since it obviously contradicts the principle of taxation according to ability to pay if the tax burden increases despite the same ability to pay – in particular, if it increases “at random”, i.e. not due to a decision of the tax legislator. Consequently, the increase in the price level must be taken into account in income taxation.[6]

Currently, this is being done discretionarily. The German federal government regularly submits a tax progression report, on the basis of which the Bundestag and Bundesrat decide on the specific tariff adjustment. With the Tax Relief Act 2022 of May 23, 2022, the tax legislator carried out such a tariff adjustment in response to the currently high inflation: The basic tax-free allowance was increased significantly, and the tariff limits were shifted “to the right” to the same extent (§ 2 Tax Relief Act 2022). In this respect, the CDU/CSU’s demand has already been met.

However, the previously practiced procedure of discretionary adaptation to inflation has two disadvantages: On the one hand, there is a risk that the inflation-related tax revenue will be viewed as fiscal assets and budgeted for, even though the state is not actually entitled to them. On the other hand, the discretionary approach can lead to the elimination of cold progression being interpreted and praised politically as a relief for the taxpayer and as a charitable act of the tax legislator – although it is only the elimination of an additional tax burden that is not justified by the tax system. As we can observe today, this view can in turn give rise to demands that cold progression be not, or not fully, compensated for.

Therefore, an “automatic” and rule-based adaptation to inflation would be the better solution. For this purpose, the income tax rate would have to be inflation-indexed. The automatic adjustment could be made on the basis of the inflation rate expected for the following assessment period, with any deviations between the expected and actual inflation rate being taken into account when adjusting the tariff for the next assessment period.

One could even go further and also call for indexation of government bonds.

Only in this way, i.e., by indexing both the tax system and borrowing, can the state be prevented from becoming the winner of inflation – and only thus can it be ensured that the state has no interest in inflation. This would eliminate any fiscal incentive to directly or indirectly promote an inflationary monetary policy.

References

Bundesrechnungshof. 2021. Bericht nach § 99 BHO zur Umsetzung der Energiewende im Hinblick auf die Versorgungssicherheit und Bezahlbarkeit bei Elektrizität. Bonn.

Deutsche Bundesbank. 2022. Monatsbericht Juni. Frankfurt.

Eurostat. 2022. Wachstumsrate des realen BIP. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/TEC00115__custom_1177235/bookmark/table?lang=de&bookmarkId=9f727da7-3466-4e82-af24-c35c703fe6f9

Pittel, Karen et al. 2022. Gaskrise 2022: Wo stehen wir und was können wir tun? ifo Schnell-dienst 75(9), 1-14.

Statistisches Bundesamt. 2022. Konjunkturindikatoren. Außenhandel. 12. September. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Wirtschaft/Konjunkturindikatoren/Aussenhandel/ahl310a.html

Vahrenholt, Fritz. 2022. Die Deindustrialisierung hat begonnen. Kalte Sonne. 8. September. https://kaltesonne.de/fritz-vahrenholt-die-deindustrialisierung-hat-begonnen/#more-70742

Notes

[1] Data source Figure: ECB, Consolidated Balance Sheet of the Eurosystem, various editions.

[2] This becomes particularly clear when comparing the situation with countries like Switzerland, where the inflation rate is significantly lower than in the euro zone despite comparable exogenous shocks.

[3] To put it simply, the terms of trade describe the exchange relationship between imports and exports. The larger this is, the more goods can be imported for a certain amount of exports.

[4] It cannot be ruled out that constitutional obstacles will stand in the way of this project. After all, “windfall profits” are already taxed. Additional taxation (with a marginal tax rate of 100 percent) will be difficult to justify.

[5] An analogous consequence would result in the case of an inflation-related fall in real incomes with nominal incomes remaining the same. In this case, the average tax rate would remain the same, although it should actually decrease. Cold progression always occurs when nominal incomes increase relative to real incomes.

[6] The same would apply to the decrease in the tax burden in times of deflation. In this case one would speak of “cold regression”. However, this case is of little practical relevance.