_ Dr. Evgeny Vinokurov, chief economist, Eurasian Development Bank and Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development. Moscow, 28. October 2022.

The Eurasian Development Bank published a new report – “International North–South Transport Corridor: Investments and Soft Infrastructure”. The study assesses the investment potential of the INSTC, identifies barriers to its development, and provides recommendations on how to eliminate them.

The INSTC is a key component of Eurasia’s transport network, as it connects to most of the region’s latitudinal routes. Its role is growing significantly in the context of “new logistics.” The corridor is the shortest route for commodity transportation between EAEU countries and South Asia, East Africa and the Middle East. It also provides a logistical choice of three routes for shipping containers, grain, metals, wood products, food and other commodities. All three routes – the Western (via Azerbaijan), Eastern (via Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan) and Trans-Caspian (via Caspian seaports) ones – have spare handling capacity.

EDB analysts have identified over 40 barriers that impede INSTC development, grouped conventionally into infrastructural and non-physical barriers. These estimates are based on surveys of transport and freight-forwarding businesses, as well as exporters and importers. The analysis showed that the factors that affect corridor competitiveness most significantly are missing links and critical infrastructure bottlenecks; lack of harmonized border crossing procedures; paper-based transport documents; and lack of an effective coordination mechanism for managing the corridor, including tariffs as well as freight and vehicle insurance.

EDB researchers have also prepared a database of INSTC investment projects using open-source data, national transport strategies and programmes. The database comprises more than 100 investment projects that are currently ongoing or being planned for implementation before 2030, for a total of over USD 38 billion.

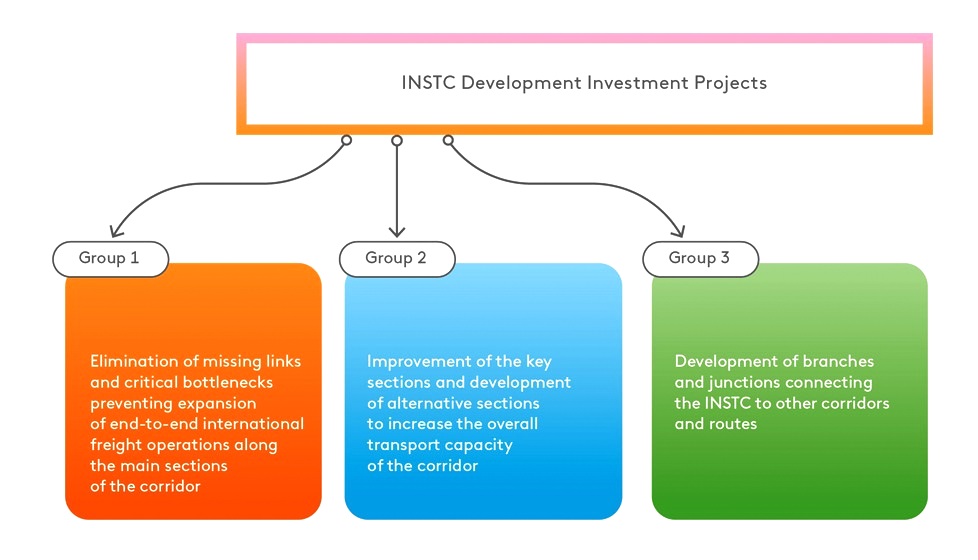

The projects have been divided into three groups. Those of the highest priority (Priority 1) are the projects which are critical to eliminating infrastructure barriers along the existing routes. These are, in particular, the projects to construct the missing Resht–Astara railway section; construct second main tracks and electrify railway lines in Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan; construct urban bypasses, upgrade inland waterways and shipping channels to standard condition and develop container and multipurpose terminals in Caspian ports; modernize border crossing points and construct logistics centres and roadside service facilities. Bank analysts estimate investment in Priority 1 projects at USD 10.7 billion.

Figure 1. Prioritization of the INSTC investment projects

Source: EDB

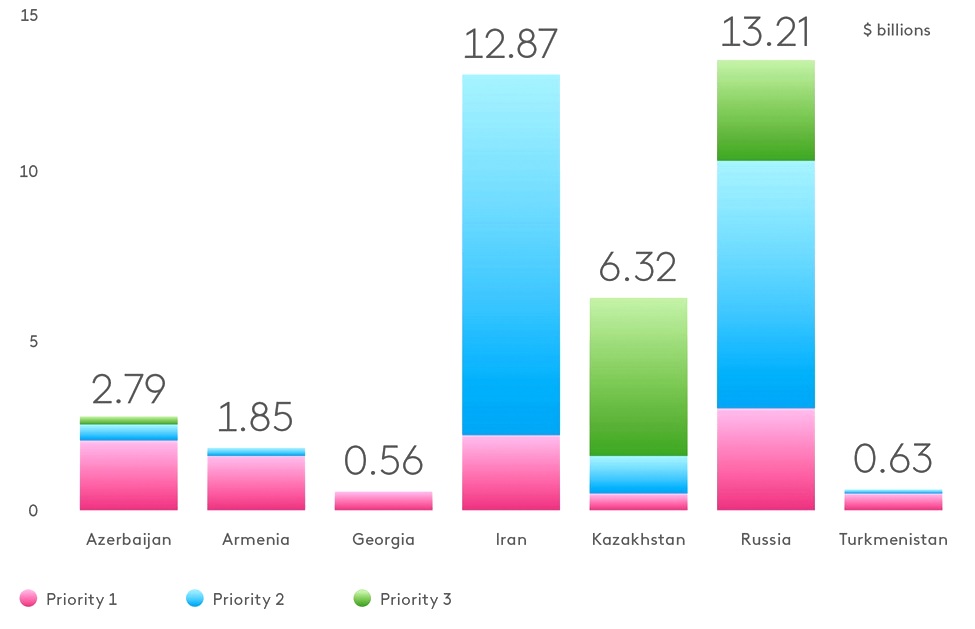

A significant portion of INSTC infrastructure development projects is being carried out or planned in Russia and Iran. These countries account for 34.6 and 33.7 percent of total investment, respectively. Kazakhstan’s share of investment in INSTC development is 16.5 percent.

Figure 2. INSTC infrastructure development projects by country and priority

Source: EDB

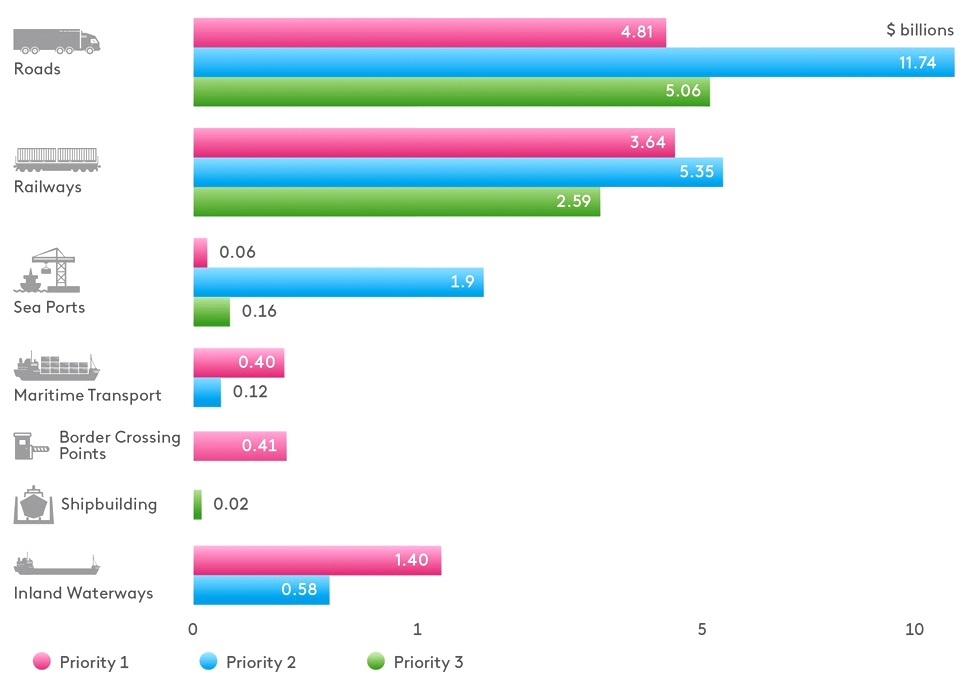

The EDB report confirms the significant capital intensity of the projects to develop INSTC land infrastructure, especially roads and railways. The number of relevant investment projects totals 59 and 20. These are worth USD 21.6 billion and USD 11.6 billion, respectively. The other initiatives include 8 projects to develop seaports, 7 projects to develop border crossing points and related infrastructure, 4 projects to develop inland waterways and 4 shipbuilding projects. To improve transport performance as well as the quality of transport and logistics services and to reduce the negative impact on the environment and climate, investment is needed in projects that upgrade rolling stock and transhipment and other equipment in seaports and at transport and logistics centres.

Figure 3. Investment in INSTC development by mode of transport

Source: EDB

State budgets continue to play a major role in financing the corridor. The share of public investment in INSTC development reaches almost 80 percent in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan and 76 percent in Russia. However, some of the projects to upgrade the fleet and rolling stock or develop roadside and logistics infrastructure are bankable and could be implemented as public-private partnerships. This would promote the involvement of private investors and multilateral development banks in their implementation.

EDB analysts believe that the development of INSTC transport infrastructure will not yield the expected results without soft infrastructure measures, including harmonization of procedures and regulations and coordination of transport stakeholders by governments and the private sector. For this reason, improving such infrastructure is critical to the INSTC development agenda.

The EDB report formulates seven groups of measures to eliminate barriers, which will help expedite INSTC operationalization and improve its efficiency. These include legal harmonization in customs clearance, information exchange and facilitation of border crossing procedures; development of a coordinated tariff policy; establishment of payment and settlement mechanisms between transport stakeholders; freight and vehicle insurance; digitalization of transport documents and procedures; and establishment of a coordination mechanism for managing the INSTC.

The new EDB study confirms that transport infrastructure projects, together with soft infrastructure initiatives, will boost and speed up freight transport not only along the INSTC but also along other transport corridors that connect to the INSTC and routes that are part of the Eurasian Transport Network.

The full version of the report “International North–South Transport Corridor: Investments and Soft Infrastructure”.