_ Nigro Montanus. Atterseekreis. September 2021.*

Parallel to the growing success of right-wing populism, the question of the reasons for its success has also become increasingly present. Be it on the part of the political media complex of parties, newspapers, NGOs and intellectuals, roughly summarized as the “establishment”, who unanimously come together in the “fight against the right” and are looking for dismantling strategies. Be it on the part of the right-wing populists themselves, who are looking for potential to consolidate and expand their previous political success.

The thesis regarding the so-called “left behind” is particularly popular, initially within the first-mentioned group. From this point of view, the “losers” of current globalization processes simply gather in the right-wing populist camp in order to express their frustration in a destructive, backward-looking way (at least from the point of view of left-wing intellectuals). A number of books have deepened this thesis and made it a common pattern of explanation, for example Didier Eribon’s return to Reims, in which Eribon, a sociology professor in the capital, describes the success of the Front National in the formerly social-democratic working-class milieu of the French provinces, or Lütten- Klein by Steffen Mau, also a sociology professor in the capital, who describes the frustration of many East Germans about broken promises of advancement and prosperity after reunification, using the example of the Lütten-Klein prefab district of Rostock.

However, what has been new for a number of years is that the right has taken up these explanatory approaches. In the course of transverse front approaches, which couple a right-wing, national-conservative-oriented critique of globalization with left-wing patterns of interpretation, the “left behind” now appear as a “social question from the right” – this time not as a latently sniffing and derogatory problem phenomenon, but as a political strategy: The “Solidarity patriotism” is intended to address those left behind with rhetoric colored by class struggle, while the left-liberal elites, the well-qualified “anywheres” are declared to be the new right-wing Marxist class enemy as neo-bourgeoisie. This attitude has gained increasing popularity in recent years and is poised to take over the opinion leadership within the right-wing opposition. But does it actually describe reality?

Is “solidarity patriotism” really the reason for the AfD successes in East Germany?

It seems as if Germany, as a chronic experimental laboratory and experimental laboratory victim of Western modernity, once again has the honor of becoming the touchstone of a political theory. Because German right-wing populism in the form of the AfD is divided: in the East German state party branches, a cross-front approach combined with an East German criticism of capitalism is in charge, in the West German, on the other hand, a more pro-American liberal conservatism. The success above all proves the Eastern associations right: They usually receive more than 20 percent of the votes, while the liberal conservatives in the West often have to be content with results in the single digits. It is therefore not surprising that the solidary patriots explain the difference with the activation potential of their program and are increasingly calling for the AfD to be aligned with their interests. But is there a connection between solidarity-patriotic program and voter support at all?

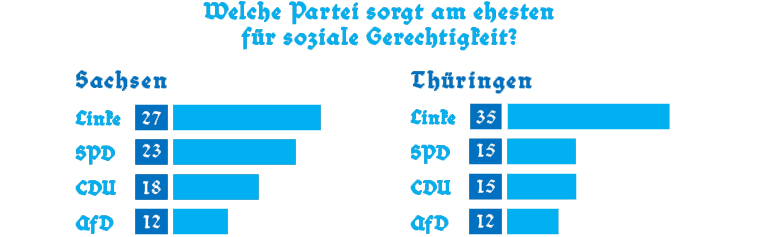

Chart 1. Which party is most likely to promote social justice (Saxony and Thuringia, 2021)?

This question can be checked quite easily: If the reason for the greater popularity in the East was actually the social orientation of the East associations, this should be visible in the polls of the pollsters, so the AfD should be perceived in East Germany as a social party and straight chosen because of their social orientation. However, that is exactly what is not evident.

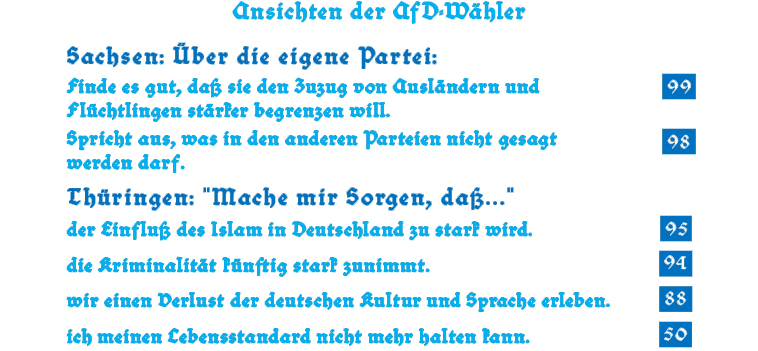

Let’s start in Saxony, where the AfD achieved its greatest success to date in 2019 with 27.5%. If you ask Saxon voters which party they think stands for “social justice”, the AfD finds itself in last place according to polls by the Tagesschau. (The Greens, intriguingly, never appear on ARD’s “social justice” questions, suggesting that they are still behind the AfD, but are protected from this unflattering exposure by silence by the pro-Green ARD staff.) Still, it has the AfD achieved an outstanding result in Saxony. However, when it comes to the motives why voters chose the AfD, we come across completely different reasons: immigration and crime are at the top of the list, protest votes also play a role, while social issues are clearly secondary.

Congruent picture in Thuringia: Although Björn Höcke, the popular symbol of “solidarity patriotism”, prevails there, the Thuringian AfD is not perceived by the general public as a social party in any way. (The issue of “wages/pensions” may at first glance appear like a potential SolPat issue, but it also appears to a similar extent in the other parties. So it seems to be a very general concern from which no specific party preference is derived.) What actually drives voters in the direction of the AfD, on the other hand, is shown by querying specific views. This is up to 100 percent the subject complex of mass migration, Islamization or, in short, what the New Right calls the “Great Exchange”. In this context, economic fears about the future also appear, of course, but it will be shown that this does not necessarily mean that there is a preference for socialist politics.

First conclusion: The AfD is neither perceived as a social party in the East nor chosen because of its social orientation.

Chart 2. Question to AfD voters: Which topic plays the most important role in your voting decision (2021)?

Explanation: Saxony: immigration 34 percent, crime 18 percent, social security 11 percent. Thuringia: immigration 34 percent, wages/pension 20 percent, crime 17 percent, economy/work 11 percent, social security 6 percent.

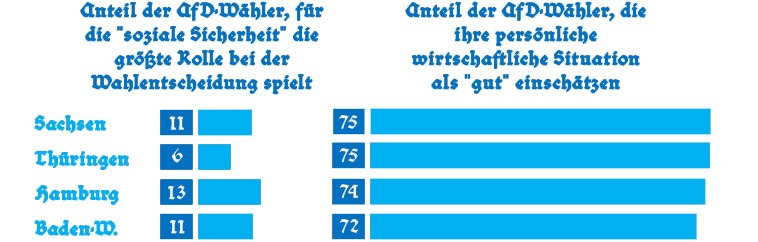

Let’s now turn our gaze to the West, more precisely to Hamburg, where a general election took place in 2020. There we encounter the opposite scenario: the AfD in Hamburg is relatively liberally oriented and with a pitiful 5.3% it just manages to get into parliament. Is there a connection here? Was the AfD in Hamburg unable to address the lower income segments, the economically frustrated, due to the liberal orientation of the election campaign? However, this quite understandable assumption is not reflected anywhere in the election polls. Instead, one encounters the remarkable fact that with regard to the social perception of the AfD between Hamburg, Saxony, Thuringia and Baden-Württemberg there is hardly any significant difference.

It is true that the proportion of those who subjectively assess their own economic situation as “bad” is significantly higher in the AfD in East and West: where most other parties have around 90% economically satisfied voters, it is the same for the AfD only around 75% each. Nevertheless, this value is still relatively high: If 3/4 of all AfD voters do not feel any acute economic problems, this can hardly be seen as a central electoral motive. It is also noteworthy that the proportion of those who feel economically oppressed is almost identical in East and West. This shows that the weak results in the West were not caused by less mobilization of the economically dissatisfied.

The second conclusion is: Whatever the reasons for the unquestionably desolate performance in Hamburg (or the generally poorer performance in the West) may lie, it is not the programmatic differences in relation to a liberal or social orientation of the respective state associations. Not every correlation is a causality – and this is exactly the classic misinterpretation here. Even though the AfD gathers the highest proportion of economically dissatisfied voters among its voters, it is also perceived as the least social party alongside the Greens.

Neither the own economic situation nor the social orientation of the AfD was decisive in the previous elections. Rather, it seems as if the AfD has long since been trapped in its own discursive parallel society: while internally increasingly bitter conflicts between the social/proletarian/”fundamental” and the liberal/bourgeois/”moderate” wing are being waged as a struggle to be or not to be, the voters hardly notice such regional program differences. The AfD is received relatively uniformly nationwide and socio-political aspects in particular are largely irrelevant across states. The question of what makes the AfD less successful in the West cannot initially be answered with this. The alleged “solidarity-patriotic recipe for success” (Benedikt Kaiser) was not, at least in the previous elections.

Is the AfD particularly successful with workers and low earners?

The first question dealt with the programmatic orientation. The second question revolves around the target group: Is the AfD particularly successful with workers and low earners or in traditional “working class milieus” such as the Ruhr area, where people are already feeling the negative effects of globalization and immigration? Can the AfD perhaps even be understood as a new “workers’ party”, as is sometimes heard from the ranks of solidarity patriots?

Chart 3. Views of AfD voters in Saxony and Thuringia (2021)

Explanation: Saxony: About your own party: Think it’s good that you want to limit the influx of foreigners and refugees more: 99 percent. Says what is not allowed to be said in other parties: 98 percent. Thuringia: I worry that: … Islam is becoming too strong: 95 percent; … crime will increase sharply in the future: 94 percent; … we experience a loss of German culture and language: 88 percent; … I can no longer maintain my standard of living: 50 percent.

Fortunately, this question was already examined in 2018 by the information service of the German economy. But here, too, it is evident that economic key figures cannot explain the AfD’s successes. AfD strongholds exist both in the highly unemployed, proletarian regions of the Ruhr area and in the rural CSU heartland of East Bavaria, where there is almost full employment. They exist both in the liberal, high-income regions of southern Germany and in the structurally weak East, which is critical of capitalism. Economically and sociologically, these regions can hardly be brought to a common denominator. They also seem to be independent of the local proportion of migrants, which is relatively low, especially in eastern Bavaria and Saxony.

The assumption that AfD voters turned to right-wing populism because they were directly socio-economically affected is therefore not confirmed. At best, as more serious attempts at interpretation show, AfD voters are characterized by a subjective sense of threat that seems to be largely independent of their objective economic situation. “It’s not about unemployment, it’s about the fear of it. Not about poverty, but about the fear of not being able to maintain one’s social position. Whether someone votes for the AfD depends primarily on subjective perception and less on objective criteria such as income,” says a study by the Hans Böckler Foundation. Economic aspects only play a subordinate role: “There is a feeling of loss of control, of being determined by others, which apparently prevails among AfD voters. People are afraid of globalization, open borders and high levels of immigration. Doubts about the functioning of democracy and the credibility of political institutions are pronounced. Many AfD voters feel neglected by politics. Only seven percent trust the federal government, compared to 35 percent across all electoral groups.”

This is an extremely important finding. Because if we turn the term “fear”, which is often used in establishment circles to pathologize and devalue unloved deviants, to the right, so to speak, then it reads: problem awareness. Of course, economic aspects are also part of the decline scenario that AfD voters fear, but they do not become aware of the problem precisely because they are affected by the negative consequences of globalization in their personal or professional environment. Instead, a value profile that supersedes one’s own social situation emerges: loss of sovereignty, rejection of migration and globalization, skepticism about the institutions alienated from it.

Chart 4. a. Percentage of AfD voters for whom “social security” plays the greatest role in their voting decision. b. Percentage of AfD voters who rate their personal economic situation as “good” (2021)

Explanation: a. Saxony 11 percent, Thuringia percent, Hamburg 13 percent, Baden-Württemberg 11 percent. b. Saxony 75 percent, Thuringia 75 percent, Hamburg 74 percent, Baden-Württemberg 72 percent.

At this point we simply do not know how these attitudes come about. Because every study only asks what is of interest to it, and since the political discourse is shaped by economistic premises – be it from a liberal capitalist or socialist point of view – only these aspects are treated systematically. But what appears from an economistic interpretation of society as “fear of decline” or is scandalized by anti-fascism activists as “racism” is ultimately perhaps this blind spot of the human constitution, which the left-liberal political elites in their obsession with utopian transformation and deconstruction neither see nor take into account want: a connection to one’s homeland, a sense of responsibility towards one’s own country and its future, the desire to preserve one’s own values, one’s own culture – even beyond the horizon of individual sensitivities.

It must be admitted that the situation in Germany has definitely shifted since 2017: while in 2017, almost at the height of the protest elections, AfD voters were still within the solid, national average, in recent years the average AfD voter has increasingly moved in the direction of ” poorly educated men of the financial underclass”. However, this development does not go hand in hand with the opening up of new groups of voters, but with going offside, with the loss of voter support and social acceptance, especially in West Germany. It’s not a reason to celebrate, just an expression of growing isolation.

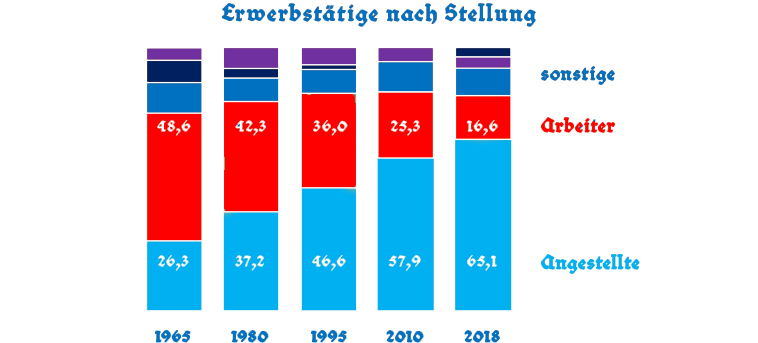

Chart 5. Employed persons according to their position (1965 – 1980 – 1995 – 2010 – 2018)

Exlanation: Manual workers: 48.6 percent – 42.3 percent – 36.0 percent – 25.3 percent – 16.6 percent.

Salaried employees: 26.3 percent – 37.2 percent – 46.6 percent – 57.9 percent – 65.1 percent.

Other: 25.1 percent – 20.5 percent – 17.4 percent – 16.8 percent – 18.3 percent.

The high proportion of “workers” among AfD voters is also correct and visible in every election analysis. Here, however, it must first be reflected that what contemporary statistics mean by “worker” is now far removed from the class-struggle clichés of the 19th century. It only expresses the type of activity: The “worker” is someone who earns his money with physically oriented work, the “employee” is someone who earns his money with primarily mentally oriented work. The boundaries are becoming increasingly blurred in the professional world of today: the entire low-wage temporary work sector definitely falls under the category of “worker”, but at the same time the skilled worker (i.e. the worker with a completed training and professional experience) is sought after on the job market and is usually well paid. Conversely, the segment of academics and executives definitely falls under the “white-collar workers”, but at the same time the broad mass of medium-earning office workers also, and especially in the social and humanities fields, the remuneration is often moderate, the employment contracts are only temporary or part-time. The difference between worker and employee today, contrary to all Marxist romanticism, is to be found in the habitual rather than in the material conditions or even class contradictions. The real problem with focusing on the working-class milieu, however, is that in the course of structural change in our western industrialized countries, it is quantitatively only a marginal group. The proportion of blue-collar workers among employees is falling from year to year and is now only 16.6 percent in Germany.

Is globalism creating a new class struggle?

At this point in the discussion, we come up against a fundamental question: why the workers at all, the precarious, the low earners, that is, roughly speaking, the economically lower half of society? In relation to the current political situation, the solidarity-patriotic perspective can be outlined as follows: From a solidarity-patriotic perspective, globalization as an eminently capitalist process generates profiteers and losers. The beneficiaries are the left-green, urban “Anywheres”, who are equated with “bourgeoisie” in the sense of a Marxist term revival. This vague group is now assumed that as economic beneficiaries of current politics, they will of course continue to choose it, i.e. they adopt a class perspective in relation to globalization, so to speak.

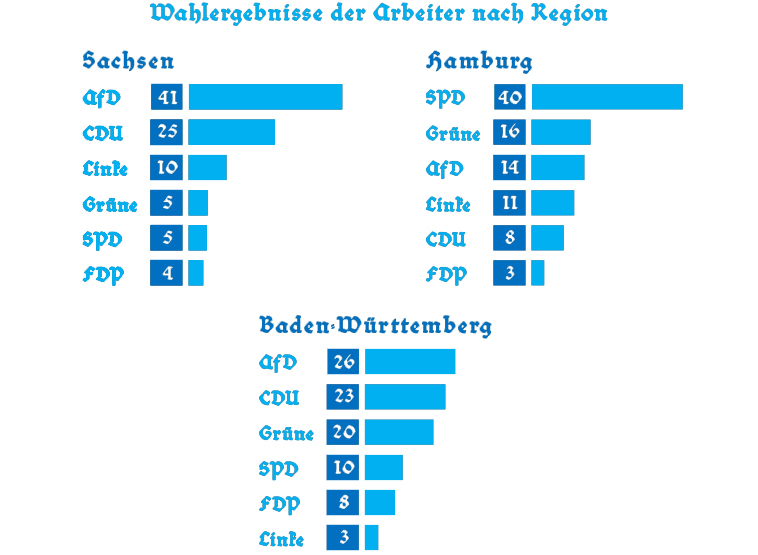

Chart 6. Workers’ election results by region (2017)

Saxony: AfD 41 percent, CDU 25 percent, Left 10 percent, Greens 5 percent, SPD 5 percent, FDP 4 percent. Hamburg: SPD 40 percent, Greens 16 percent, AfD 14 percent, Left 11 percent, CDU 8 percent, FDP 3 percent. Baden-Württemberg: AfD 26 percent, CDU 23 percent, Greens 20 percent, SPD 10 percent, FDP 8 percent, Left 3 percent.

The losers, on the other hand, a group in which terms such as “workers”, “people” or “lower class and middle class threatened with decline” are mixed up just as undifferentiatedly, form the potential reservoir of voters of socialist-oriented right-wing populism. Because they are the losers of globalization and mass immigration, they are exposed to competition from the global market as well as to competition and increasing displacement by migrants. At the same time, the formerly left-wing parties have largely given up on the lower and middle classes and are only committed to new left-wing prosperity issues such as the energy transition or LGBT. In a way, the fruit is ripe to be picked, and all that the right-wing still needs is “solidarity patriotism” – or as figurehead Björn Höcke puts it: “Only with a clear socio-political profile can the large group of voters, the “little people « that suffers the most from the unreasonable demands of globalization, climate madness (electricity prices!) and the consequences of migration.”

But for this scenario to work as an AfD winning strategy, two key assumptions must be true: First, the number of economically dissatisfied people must be high or at least grow due to the current policy. And secondly, this circle must primarily be activated by left-wing programs. However, the reader may already suspect that these assumptions are again not confirmed in reality. At least as far as economic parameters are concerned, the policy under Angela Merkel seems to be a model for success. Economic satisfaction grew steadily for 15 years, and the mass migration of 2015 had no impact. There is no longer any significant difference between East and West. It remains a mystery where there is a “middle class threatened with decline” that is supposed to perish under the “impositions of globalization”. You have to describe it as wishful thinking.

And even the association between the working class and a socialist worldview turns out to be a mere cliché on closer inspection. Rather, what the worker chooses is strongly dependent on regional milieus: in a classic social-democratic way, they only choose in the urban areas of western Germany such as the Ruhr area or Hamburg. In the AfD stronghold of Saxony, on the other hand, a federal state that has been governed by the CDU since the fall of the Wall and has had the best economic development of all East German states, it is not the social democracy, but the liberal-capitalist CDU, which mainly compete with the AfD for the workers votes competed. And also in Baden-Württemberg (not to mention Bavaria) the working-class milieus are traditionally jet black. Especially in southern Germany, especially in rural areas, socialism and the “workers’ movement” it self-proclaimed as a socialist interpretation of social processes never had much sympathy; on the contrary, the aversion to “the reds” is often deeply rooted there.

“I think this war against the liberals or the liberals in the AfD is catastrophically wrong, because you could totally agree on the point of normality. This anti-capitalist reflex, here the worker, there the exploiter […], I think that is a fight that is not at all up-to-date.”

– Götz Kubitschek, Institute for State Policy (2021).

Pensioners and civil servants are slightly over-represented in the electorate, while white-collar workers are slightly under-represented. The latter has also applied to workers since the 1980s, which underscores the character of the CDU/CSU as a cross-class people’s party. Since reunification, the Union has only recorded major slumps in this group in the federal elections of 1994 and 1998. Since 2009, it has even been ahead of the SPD in absolute numbers among workers,” reports the Federal Agency for Civic Education about the CDU electorate.

So while the transverse front strategy amounts to targeting the ever-growing number of economically oppressed with socialist policies from the right, in reality there is neither a growing number of economically oppressed, nor are these lower strata predominantly socialist-oriented. Absolutely, so much is conceded, the welfare state orientation in the German people is well developed, social issues undoubtedly play an important role in every election campaign. Nevertheless, as tormenting as this thought may be for the convinced solidaristic patriot, a significant part of the German working class and petty bourgeoisie is traditionally pro-capitalist and pro-liberal in orientation – although perhaps less of a neoliberal predatory capitalism in the sense of Milton Friedman and the US neocons may be understood as rather the Germanized “social market economy” of Ludwig Erhard, i.e. a capitalism with conservative value orientation and social balance.

Conclusion

The division of Germany that continues to this day makes it possible to examine voter motivation more closely on an analytical level and possibly also to draw conclusions about other European countries. But it turns out that the adaptation of left-wing approaches, which primarily explain voting behavior on the basis of socio-economic parameters, simply does not work here. Solidarity-patriotic programs have no visible influence on the electoral successes in East Germany, nor is it primarily in precarious or proletarian milieus that the AfD finds favor. On the contrary: while both traditional leftists and, ironically, conservatives often accuse the new, postmodern left of betraying the working class, social developments prove this aversion to be right. Because the “worker” has long been a milieu that is quantitatively disappearing.

But what is it that drives AfD voters, supporters of right-wing populist parties in general? Unfortunately, the answer to this remains in the dark, at the end of this investigation we are left empty-handed, only richer in the knowledge that the supposed pot of gold “solidarity patriotism” was only painted tin. Instead of just adapting popular left-wing approaches, the right-wing camp will have to produce their own studies and develop their own approaches and theories in order to gain a deeper understanding of their own meaning. Much remains to be done.

* Translated and republished with kind permission by the author from the original publication on: Montanus N. (2021). Rechtspopulismus und soziale Frage. Attersee Report Nr. 30. URL: http://www.atterseekreis.at/PDF/2021-09-Attersee-Report.pdf