_ Dr. Vaclav Klaus, economist, Prime Minister from 1993 to 1998 and President of the Czech Republic from 2003 to 2013, CEO, Vaclav Klaus Institute. Prague, 4 April 2023.

The Czech public, including the vast majority of economic commentators (not to mention the Czech economic community, which does not exist), seems to be lulled by the slight decline in the rate of price growth on the one hand and the apparent calm of the government on the other. The latter pretends, and probably thinks, that nothing dangerous is happening. Perhaps today’s meeting is also an opportunity to say that something is happening.

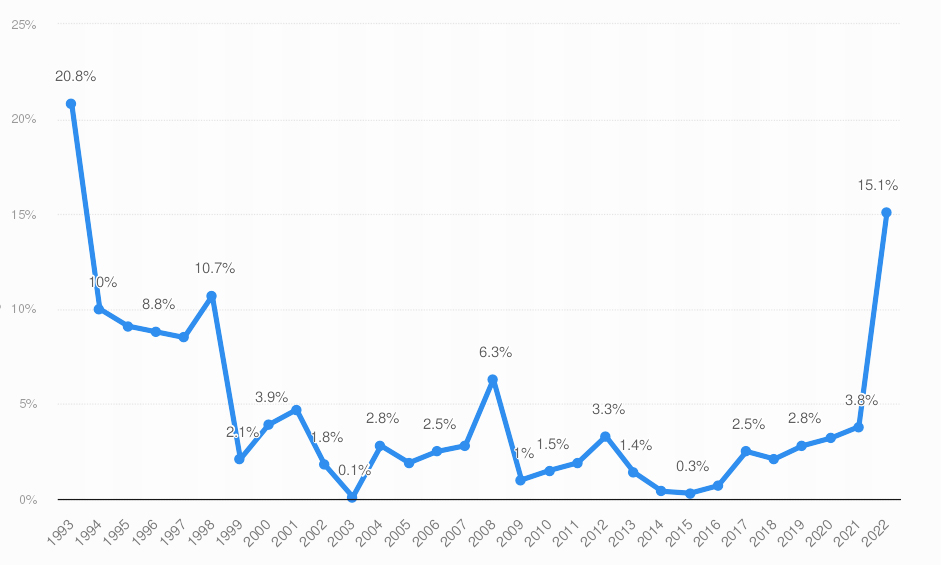

Graphic 1. Average annual inflation rate in the Czechia from 1993 to 2022 (in percent)

Source: Czech Statistical Office (2023).

The government may be having its theatrical battles with the opposition, most recently over pension indexation, but it is not willing to do anything about its culpability for the continuation of our current inflation. Perhaps it does not really realize its guilt. The deficit financing of the state budget does not bother it.

It is our duty to bring the Czech government out of this unwarranted lull. Inflation is not over in our country. It is not ending in other countries of the Western world either, but the vulnerability of our economy is much greater for various reasons – determined by the structure of the economy, the structure of foreign trade, the extremely low unemployment rate, the lack of domestic energy resources (either real or the result of a completely irrational acceptance of the tragic errors of green ideology). That is why our inflation rate is clearly higher than in Western European countries and than in the USA.

It is trite to say that inflation is not a natural disaster. It is man-made, it is made by humans. It is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. Either it is enabled by too lax monetary policy, or it is induced by activist monetary policy. Either way, inflation is the result of too much money in the economy – relative to output. The famous quantitative equation of exchange always holds. It is an accounting tautology.

Slowly, the public and our ministers are no longer confusing the rise in individual prices with inflation. It is impossible to confuse relative prices with absolute prices. Inflation is a rise in the price level. Let us therefore not get carried away with describing the causes of supply chain distortions and the birth of bottlenecks in the economy. Both play a role right now, of course, but without excessive growth in the quantity of money in the economy, no inflation can arise. Let’s not blame it on the chip shortage or the war in Ukraine. Even before that war, we had an inflation rate of more than 10 percent, something we have not seen for more than two decades. Therefore, a responsible person should not make the debate easier by blaming our domestic inflation on the war in Ukraine.

Excess money has been created in this country for many years, from the Great Recession at the end of the noughties until the summer of 2021, when the Czech National Bank put the brakes on and started raising interest rates. Although inflation persists and is much higher today than it was when interest rates were first raised in this country, the central bank has stopped raising interest rates. This is clearly a mistake by the new CNB management.

To be fair, however, we should acknowledge that in one sense the CNB is “right”. The government – through its budgetary policy – is more responsible for determining the dynamics of inflation in our country today than the central bank through its monetary policy. We have been experiencing inflation for almost two years now, but the government’s budgetary policy has not yet put the brakes on. The government may be “deflating balloons” on individual items such as pension indexation or, for example, increases in gambling taxes or property taxes, but it has not yet announced the goal of a restrictive, i.e. anti-inflationary, budgetary policy. I fear that it will not even announce it, because it fears the word like the devil. It is not only afraid of the word, it is afraid of what this policy would do to its popularity.

With its huge budget deficits, the Czech government is pursuing the opposite policy, an inflationary policy. Experience tells me that it is necessary to recall the development of the state budget balance in recent years, not everyone has it in front of their eyes.

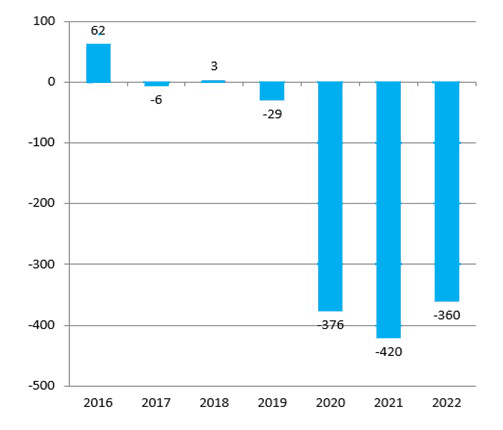

Graphic 2. The balance of the state budget of the Czech Republic (CZK billion)

Source: Czech Statistical Office (2023).

It is sad that the same large deficits that were seen in 2020, 2021 and 2022 are planned by the government for the rest of its term. This must be described as unacceptable. I don’t want to put too much spin on yesterday’s reported figure for the size of the national budget deficit for the first three months of this year – 166 billion Czech koruna – but not saying so is impossible. Inflation cannot be eliminated without a radical reduction in the budget deficit. We are in a budget trap, and we must try to get out of it. That this is not and will not be painless is obvious. It will have a considerable political cost, because it will require interventions in the nature of the existing system and in the behavioural patterns (or habits) of millions of people. It will also have economic costs. Furthermore, it will result in a halt to economic growth and most likely an economic downturn.

But the costs of inflation are already great. Inflation is a large-scale economic phenomenon that has “seeped” into all corners of human life and is dividing society. It does not have the same consequences for everyone. Inflation is always and everywhere a great redistributor, or redistributor of wealth in society, not directly organized by anyone, and it chaoses society. It gives wings to some and destroys others. The holders of money lose, the recipients of fixed incomes lose, the creditors lose. Other groups of economic agents profit from inflation – borrowers, flexible income earners, risk-taking investors, and especially the state. In order to be eliminated, inflation requires a severe intervention in the life of society and in the functioning of the economy. If the finance minister does not know where to restrict, then the clue is clear – the restriction must be across the board. In the situation of a completely inhomogeneous five-coalition government, there is probably no other form of restriction possible.

Our current inflation – the highest in 100 years – needs to be seen in the wider context of what is happening in, or to, the whole of Western society. That broader context is the long-standing revolt against economics, against economic thinking, against respect for economic laws, and in turn the tolerance of politics overtaking economics, or the dictates of politics over economics. Politics of various colours, today especially the colour green. These are defects we know well from the communist era. They have come back to us without central planning, without nationalization and without the monopoly of one political party with a new power.

Unlike communism, we have not yet seen the destruction of the possibility of gathering and associating. Therefore, there has been no liquidation of pressure groups, professional organizations, trade unions, chambers, activist, so-called non-profit organizations, and these groups are responsible for radically strengthening the phenomenon of the so-called “entitlement society”. This represents a paradigm shift in the thinking and behaviour of individuals and their various groupings. Inflation cannot be solved without an intervention in “entitlement” (a return to meritocracy).

Economists (and along with them central bankers and finance ministers) – quite wrongly, irresponsibly and ahistorically – thought, after a period of deflationary fears, that the inflation that emerged would be only “transitorient” (transitory or temporary), which was a totally unsustainable and untenable fallacy. Even the sophisticated US Federal Reserve Bank fell for it.

I see this as a new victory for Keynes and Keynesianism over Friedman and monetarism. I see this as a victory for Stephanie Kelton (well, the Keltonians) and her MMT, or Modern Monetary Theory. For a long time, economists didn’t take these theories seriously because they thought they couldn’t be taken seriously. The main thesis of these theories is the idea that “deficits don’t matter” and that governments can print as much money as they need.

The Swiss economist Claudio Grass put it succinctly in his commentary of 10 March 2023 when he said that MMT is “a political strategy disguised as an economic theory”. I consider it indisputable that belief in this way of thinking has contributed to the current excess of money in the economy. Unfortunately, many politicians almost always think what MMT says, but now someone has offered them the excuse that there is a scientistic economic theory behind it. It isn’t.

Keynes, after all, thought so too. The velocity of the circulation of money, another variable in the aforementioned quantity equation of exchange, was, in his view, completely unpredictable, which is why he held that there was no telling what changes in the quantity of money would do to prices. (This is nicely interpreted by Peter Smith in the Australian Quadrant, 13 September 2022.) MMT apologists recommend that policymakers choose a combination of budget deficits and low interest rates as the optimal strategy. Czech Prime Fiala and Stanjura are probably inspired by this theory today and every day.

The well-known American inflation expert John H. Cochrane turns his attention to the fact that the central bank alone cannot beat inflation. Its harsh intervention would lead to a long and deep stagnation. Fiscal policy must also play a key role. And not only that. Relying on monetary and fiscal policy alone would require a healthy economy. Because neither the U.S. nor our economy is healthy, flexible, eliminating inflation, according to Cochran, requires making broader economic reforms at the same time (Hoover Digest, Winter 2023). In my terminology, it requires removing the over-regulation of the economy (both European and Czech), getting rid of green ideology and suppressing entitlement in the thinking of economic agents. That’s how simple it is.

* The invitation to today’s meeting was headlined “Czech Republic in the vortex of inflation – a momentary blip or a structural threat?” My answer to that question is perhaps clear: our inflation is the latter.