_ Jorge Núñez Ferrer, Senior Research Fellow, CEPS. Brussels, July 2020.

In a nutshell, the major decisions taken are the following:

- a) The level of grants in EU Recovery Fund (Next Generation EU) was cut from EUR 500 billion to EUR 390 billion.

- b) The reduction was offset by an increase in the level of loans from EUR 250 billion to EUR 350 billion, thus keeping the size of the package intact. The increase in the lending arm of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (placed under the Cohesion Policy heading) is done at the expense of grants that were allocated under other headings of the next EU budget (MFF). The grants under the Recovery and Resilience Facility were in fact not reduced.

- c) The size of the MFF 2021-17 was cut by EUR 25.7 billion compared to the May 2020 proposal.

- d) The Council introduced some commitments to create new own resources. What do those changes mean in practice and what has been agreed in particular?

Many commentators seem to think that there are free transfers and grants without conditionality, with the loans promoting more responsible behaviour by governments. This is questionable in view of the rules that are generally attached to grants. In addition to the programming process, EU budget grants are subject to a large number of conditions and controls. Loans (as proposed), on the other hand, can be spent quicker and are subject to fewer conditions. The agreement, however, does not clarify to what extent Next Generation EU grants will be under similar controls to those under the normal budgetary rules.

What is certainly a factual result is that for the Next Generation EU, the redirecting of grants to loans means a weakening of the alignment of expenditure to EU priorities in the areas of climate policy, innovation, security and defence, and health. Of course, member states have the freedom to allocate the funds they receive as grants or loans in those areas, but they are unlikely to do so, at least not to the extent originally intended. For the energy transition the funds require complex strategies and planning, and impacts are slower to materialise, even if they are more geared to the needs of the future. The large Just Transition Fund would also have pushed for a decisive move out of coal power stations and mining, a move not favoured by some member states, such as Poland. For Horizon, access to funding requires national research centres to have the capacity to compete for funding. A number of countries lack the capacity to compete successfully for this funding which explains the outcome.

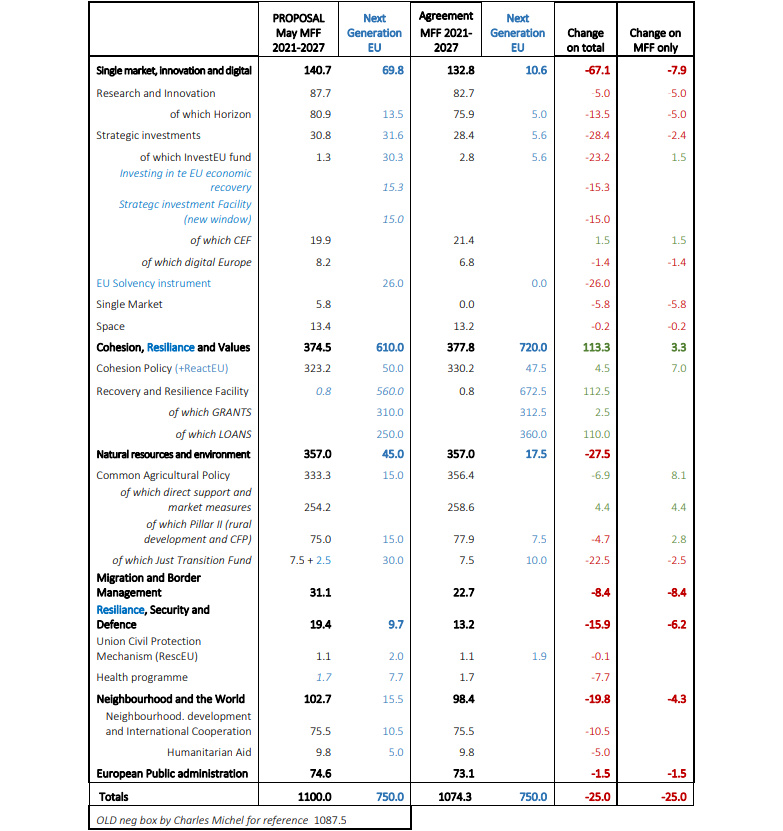

Table 1 below compares the Commission proposal for the MFF 2021-27 and the May 2020 Next Generation EU with the agreement of the European Council.

Another move was the deletion of the EU solvency instrument to assist otherwise solvent businesses hit by Covid-19. Of course, member states are free to use their own funds or Next generation EU funds for this, but the issue here is that there will be less conditionality on the kind of companies supported, i.e. in terms of ‘solvency’ or alignment to wider EU objectives.

Table 1. Main changes in headings and affected* sub-headings, EUR billion, 2018 prices

*Only affected subheadings appear, adding them up will not amount to the full allocation of the Heading. Figures in blue under the MFF were added by the Commission for the May 2020 proposal.

The extra support under the Next Generation EU for external action was also deleted – disregarding the fact that the Covid-19 crisis will bring additional hardship to developing countries. This may well affect the EU too, as further economic decline is likely to bring more instability to developing countries, thereby fuelling migration, for example.

The move was also accompanied by a reduction to the proposed MFF, without the Next Generation EU, from EUR 1087 billion to EUR 1074 billion in 2018 prices. This move not only cut funding in a number of areas, but also redistributed funding. On cuts, EUR 7.9 billion were slashed under the ‘single market, innovation and digital’ heading; with the main blows falling on the Horizon, single market and space sub-headings. The Connecting Europe Facility and InvestEU, on the other hand, see slight increases in allocation.

Also telling is that the Common Agricultural Policy allocation has been safeguarded and includes an increase in direct payments to farmers, compared to the previous proposals. The impact is highly questionable, as the bulk of direct support is still being delivered on the basis of historical allocations and hectares. The funding is insensitive to the actual costs of complying with any ‘greening’ requirements or the financial situation of specific farms. Of particular concern is that the EU, despite the rhetoric, has decided to keep the Horizon budget close to the present levels and to protect pre-allocated budget lines. These proposed cuts have not been well received by the European Parliament, so there may still be some marginal reshuffling to come.

The Council conclusions do introduce an agreement on new own resources, with the stated objective to raise funding to repay the Next Generation borrowing. It agrees on the introduction of a levy on non-recycled plastics proposed by the Commission, starting 1 January 2021. The estimated yield of the plastics levy was estimated by the Commission to amount to EUR7 billion, not enough to cover the repayment of the loan. In addition, this levy should most likely diminish over time, as single use plastics are expected to be phased out. The Council thus asks the Commission to draft proposals for a carbon border adjustment levy and a digital tax, in view of their potential introduction in 2023.

Other resources are also to be explored by the Commission in view of their eventual future introduction. First, a share of the ETS (Emissions Trading System) revenues, possibly extending it to the aviation and maritime sectors. Second – lo and behold – the FTT (Financial Transaction Tax) makes a remarkable comeback. The absence of the Common Corporate Tax is telling, however.

Of these resources, we may only see the plastics levy emerge, and maybe a share of the ETS during the 2021-27 period, because all other options will face particular resistance. The carbon adjustment levy will probably need years of negotiations with the US and China, as otherwise the EU would risk a damaging trade retaliation. The same is true for the digital tax and relations with the USA. The year 2023 is probably an overambitious and unrealistic target. To some extent their introduction may depend on the outcome of the US presidential election.

Despite the clamour during negotiations about control over member states’ expenditure, it is questionable whether this outcome is an improvement on the European Commission’s May proposal of the Next Generation EU. The agreement requires member states to prepare a reform and investment agenda, which needs to be assessed by the European Commission and approved by the Council. In the Commission’s proposal member states were also required to align their actions to the European Semester and the National Reform Programmes, and have them approved by the Commission, which is equivalent to the requirements now. The difference is mainly that the Council also has to rubberstamp them by qualified majority vote (QMV). Does this make for a significant difference? It is certainly a politicisation of the process but does not give the ‘frugals’ (Austria, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden) too much power to veto programmes, as the four, even with Germany, would still not have enough weight to block a member state proposal.

Among these stipulations, the agreement proposes an increase to the collection costs of customs duties from 20% to 25%, which is mainly an increase of the hidden rebate to the

Netherlands, as the actual costs are estimated to be in the range of 10%. Additional corrections have been included for the frugal four (plus Germany) amounting to EUR 7.6 billion, close to the rebate they received for their contributions to the UK rebate. An unfortunate legacy of UK membership.

Overall, it is difficult to see a marked improvement in terms of quality or financial control on the Next Generation EU, which represented a stated fundamental concern for the four frugal countries. Many funds that were allocated to specific EU priorities are now largely bundled under the overarching Recovery and Resilience Facility. This gives member states more power of discretion over the allocation. Whether grants or loans are better in terms of control and incentives depends on the rules governing both, because the conditionality and controls over the normal MFF grants are substantial.

A clear impact of the increase in loans is to reduce member states’ contributions to the EU’s own resources for the repayment of the bonds issued to raise the EUR 750 billion. This appears to be the only undisputed objective achieved by the frugal member states – not the quality of expenditures. For the main beneficiary countries, a higher share of lending may be a blessing in disguise. While the loans do increase their public deficit, they provide greater freedom of action and fewer potential problems with using the funds; after all, they have to repay them.

There is still uncertainty about how exactly the grants will be used in the timeframe required (committing and spending the bulk of the funds in the years 2021 to 2024) and under which process and controls. Member states have found it difficult to absorb existing EU grants.

Nevertheless, the agreement is extremely vague on the level of financial control. The agreement invites the Commission to propose how to protect the Next Generation EU from fraud and irregularities, but it is unclear what this means. It would be logical to apply the procedures in place for the MFF for grants that are under the close scrutiny of the EU, and these are rather burdensome.

And then there are the controversial ‘rule of law’ provisions. The text on the rule of law is rather funding for ‘generalised deficiencies’ in the rule of law is questionable when breaches to the rule of law are not related to the financial interests of the EU (Articles 2 and 49 of the Treaty of the European Union define ‘generalised deficiencies’). While a corrupt legal system that puts the financial interests of the EU at risk presents clear grounds for suspending financial support, this is not the case for those not presenting a financial risk, e.g. the appointment procedures for judges to the constitutional court. Again, the text is ambiguous on which kind of rule of law deficiencies constitute grounds for the de facto suspension of payments by qualified majority voting (QMV). On the one hand, it is worth noting that a coalition of countries presently considered to be in violation of EU rule of law principles would not be able to block the suspension under QMV rules. On the other, such a suspension could be challenged at the European Court of Justice if no financial interest is at stake.

To conclude, although the agreement is certainly an impressive one, the impact of the hardwon compromise on the overall package is not all we may have believed. vague and open to interpretation, and is thus relatively toothless. The concept of blocking EU funding for ‘generalised deficiencies’ in the rule of law is questionable when breaches to the rule of law are not related to the financial interests of the EU (Articles 2 and 49 of the Treaty of the European Union define ‘generalised deficiencies’). While a corrupt legal system that puts the financial interests of the EU at risk presents clear grounds for suspending financial support, this is not the case for those not presenting a financial risk, e.g. the appointment procedures for judges to the constitutional court. Again, the text is ambiguous on which kind of rule of law deficiencies constitute grounds for the de facto suspension of payments by qualified majority voting (QMV). On the one hand, it is worth noting that a coalition of countries presently considered to be in violation of EU rule of law principles would not be able to block the suspension under QMV rules. On the other, such a suspension could be challenged at the European Court of Justice if no financial interest is at stake.

To conclude, although the agreement is certainly an impressive one, the impact of the hardwon compromise on the overall package is not all we may have believed.

Source: https://www.ceps.eu/