_ Hans-Werner Sinn, Dr. Sc., president, ifo Institute for Economic Research (1999-2016), member, advisory council, Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (Germany); professor emeritus, Ludwig-Maximilian-University. Munich, 18 November 2018.*,**

The Italian government blackmails the EU in the debt dispute. The Euro rescuers have gotten themselves into this with their many relief loans.

The current conflict between the EU and Italy can be discussed in a moralizing tone and the alleged excessiveness of the Italians can be scourged. But this conflict can also be interpreted as the result of stormy and ill-considered communitization actions in Europe, which have done serious damage to European integration.

Italy’s national debt has long been high, and huge stocks of credit claims have been dormant in Italian banks for a long time. The EU Commission should have regulated banks more strictly years ago and limited government debt, but it did not. The fact that it is suddenly upset about a deficit ratio of 2.4 percent is due to the fact that new eurosceptic parties have emerged as competition to the old establishment in Italy. The commission wants to make an example of them now. After the Italian government refused to reduce the planned budget deficit, the EU Commission could impose heavy fines. Italy does not want to pay these fines, but seeks the open conflict. A friendly solution is no longer sought. Italy’s government was chosen to take more radical steps. And it is measured by the population by whether it can meet these expectations.

Italy’s history in the euro is a history of public loans and guarantees, of community guarantees and grants that have kept the country afloat. All of these aids have worked like drugs that calmed the financial markets and the population. But they have made no contribution to solving Italy’s structural problems. Rather, they have destroyed Italy’s competitiveness and increased the country’s debt dependency.

The Italian state was almost ready for bankruptcy as early as the 1990s. Government debt was 120 percent of GDP, and Italy had to pay more than 12 percent interest on its ten-year government bonds. The interest burden was unbearable, the collapse of the state was foreseeable. More and more new debts were taken up to service the old debts and even to pay for a part of the ongoing interest. The euro now had to be introduced in Italy in order to reduce the interest burden. In fact, Italy’s interest rates already fell in anticipation of the euro by about five percentage points almost to the German level, which was then around 7 percent. Despite the no-bail-out clause of the Maastricht Treaty, investors were confident that the euro countries would now be protected from a state bankruptcy. It was assumed that Italy would either print the money to repay its debts or that the other countries would help Italy directly, which both actually happened later.

The euro was initially a blessing for the Italian state. The common currency saved Italy so much interest that it could have cancelled its VAT. If Italy had used the interest saved to pay off its debts, the debt ratio would be well below 60 percent today. But Italy acted differently. The state not only spent the interest savings, but also took the opportunity to get more and more in debt. The double surge in spending increased aggregate demand, which caused prices in Italy to rise faster than in the rest of the eurozone. From 1995, when the introduction of the euro was decided, until the outbreak of the Lehman crisis in 2008, Italy, including an initial appreciation of the lira compared to Germany, has become around 40 percent more expensive if one looks at the price index of the self-produced goods (this index matters when it comes to competitiveness comparisons). No country can survive such a gigantic “real appreciation” without damage.

The overpricing was manageable as long as the capital markets were ready to finance Italy’s growing current account deficit. But when the capital markets refused after the Lehman bankruptcy, the supposedly good time was over and Italy got under the wheel. The loss of competitiveness came to the fore. Unemployment rose to around 12 percent and youth unemployment temporarily rose to over 40 percent. Deducting new start-ups, a quarter of manufacturing companies perished on a net basis. It is understandable that the nerves of Italians are bare today and that they no longer want to know anything about the EU: only 43 percent of them want to stay in the EU, less than anywhere else in the EU.

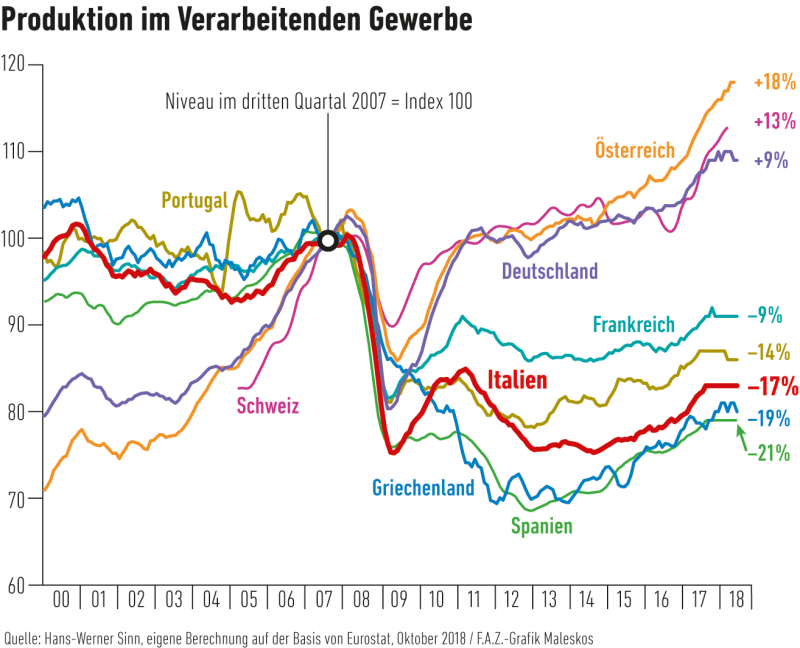

The euro has also not gotten well in the other countries of southern Europe. As figure 1. below shows, no southern European country has managed to bring industrial production back to the level it had at the beginning of the financial crisis in the past ten years. While the German-speaking countries quickly overcame the crisis and are now 9 percent (Germany) to 18 percent (Austria) above the pre-crisis level, Italy is down with minus 17 percent. France, whose sales markets are in the south and whose banks have lent a lot of money there, shows a decrease of 9 percent compared to the pre-crisis level.

Fig. 1. Manufacturing index of selected EU countries (III 2007 = 100 percent)

Source: Estimates by Hans-Werner Sinn using Eurostat data from 2018.

Long-time Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, as ex-ECB director Lorenzo Bini Smaghi reports, conducted secret negotiations in the 2011 downturn on Italy’s exit from the euro zone. The Greek Prime Minister Papandreou did something similar at the time, as he confirmed in 2016 on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference. Both wanted to make their countries competitive again through devaluations. But they were forced by the banks and key EU forces to give up their positions before they could implement their plans. Both resigned in the same week at the end of 2011. A radical leftist government later came to power in Greece. In Italy, the subsequent prime ministers Monti, Letta, Renzi and Gentiloni tried reforms, but they achieved little to nothing – at least nothing that could have turned the tide for Italian industry.

In the crisis, European politics did not rely on structural reforms of the Eurosystem, but on financial bailouts, because such actions helped banks and investors from France, Germany and other countries at the same time. The bailouts started with the TARGET overdrafts, which Banca d’Italia approved through a self-help campaign. Then came the ECB’s Securities Markets Program, which forced the northern central banks to buy Italian government bonds beginning from summer 2011. Because that was not enough for the markets, ECB President Mario Draghi made his grandiose protection promise (“Whatever it takes”) in 2012, which implicitly turned the government bonds of the euro countries into eurobonds and held Europe’s taxpayers liable without being asked. The permanent fiscal rescue package ESM rounded off the protection promise. In 2015, the ECB’s quantitative easing program finally came, under which government bonds from the euro countries were bought for € 2100 billion, of which a good 17 percent were attributable to the buybacks of Italian papers by the Banca d’Italia. This action catapulted the Banca d’Italia’s TARGET debt to EUR 490 billion.

All of these programs have prevented investor losses in France and Northern Europe and made life in the south more bearable, but at the same time they have hurt Italy’s industry by supporting wages higher than the actual labour productivity level, created in the pre-Lehman bubble. Anyone who thinks that Italy’s new current account surplus proves that the country is out of the worst is overlooking the fact that this surplus came about almost solely from the crisis-induced slump in imports and the interest rate cuts on foreign debt.

The lie from the “time for reforms” that would be bought with the aid has turned out to be what it was from the beginning: a public relations trick of politicians who are short-sighted and who aimed to postpone painful but necessary reforms of the Eurosystem. The failure of the aid programs clearly shows the EU’s misguided believe that politics can create more discipline than the market. Private investors slow down debtors when they become excessive. They stop the loan or charge interest rates so high that the debtors lose their appetite.

This is the basic principle of the market economy and of functioning federal systems alike. Just think of the financial hardships in the individual states of the United States, which are already using debt ratios of around 10 percent, or the discipline that the capital markets demand from the Swiss cantons. The ECB and the international community have undermined this basic principle by lowering the interest premiums of the heavily indebted countries through various systems of joint liability, starting with the euro itself, and then hoping that member ztates can be kept in check by legal means. The naivety of this belief is relentlessly revealed by the new crisis in Italy.

There are now only four options for dealing with the overpricing of Italy. The first is to sneak into a transfer union. Debts are first secured collectively. Then private creditors are replaced by public creditors, debts are stretched and eroded by waiving interest rates. Finally, the taxpayers of the other euro countries give the debtors money so that they can service their debts to the financial investors, continue shopping with their export companies and, not least, to prevent them from leaving the euro.

That would make the whole of Italy what the Mezzogiorno is already: an overpriced transfer recipient that will never be competitive again and must be supplied permanently from outside. The transfers would essentially be bribes for the relevant political groups, so that they don’t rise up against Brussels for a few more years. In fact, Europe cannot afford this because, given the increasingly difficult global competitive situation, it has to become economically stronger rather than weaker. Nevertheless, this path has long been taken. And the French government insists that it go ahead with a common deposit insurance for the banks, a shared unemployment insurance and a euro budget. There is talk of exogenous “asymmetric shocks” that have to be insured – as if the crisis in southern Europe had something to do with uncontrollable and temporary random events.

The second way is to lower prices to correct the over inflation in the early years of the euro. That means lower wages – or productivity increases that employees don’t participate in. The former is chemotherapy for the economy that could drive the patient to despair. Tenants and debtors would be forced into bankruptcy because their payment obligations would remain even though wages were falling. The latter requires not only a productivity miracle, but also an insight that the Italian trade unions have not yet shown. While Greece became 12 percent cheaper in the euro crisis than its competitors in the euro area and Spain 8 percent cheaper, Italy did nothing at all: since 2007, the price level of self-produced goods has risen exactly as fast as that of competitors in the euro area.

The third conceivable way is to increase inflation in the northern EU countries, especially Germany. Italy’s real appreciation vis-à-vis Germany since 1995 has been 39 percent to date. To compensate for this, Germany would have to inflate 2 percent a year faster than Italy for 16 years. The Italians could not stand it and the German savers would go on the barricades.

The fourth way is for Italy to temporarily exit the euro in accordance with Wolfgang Schäuble’s Greece plan of summer 2015, which 15 finance ministers from the Ecofin Council had already agreed to informally. The problem would be the expected capital flight before the exit, which Italy would have to face with capital controls until the exit is completed. From an Italian perspective, this path would have some advantages. The economy would quickly regain momentum due to the expected devaluation, domestic credit relationships would remain in balance because they would be devalued, and even some foreign debt could be converted into lira and devalued. But this would hit France’s banks, which are about three and a half times more exposed in Italy than the German banks. In political terms, this step would also amount to an oath of disclosure by Europe’s leading politicians. And the capital markets would experience considerable turbulence.

Obviously, neither of these approaches offers an easy solution to Italy’s problems; least of all the fiscal union idea which is likely to be chosen under the influence of the lobbies of the financial and export industries. The eurozone has reached a dead end. Italy’s new government knows all of this. It categorically excludes the second way (price cuts) and can realistically not expect any success for the foreseeable future via the third way (post-inflation in the north). It therefore initially focuses on the first route (transfer union) and keeps the fourth route, the temporary exit from the EU, more or less clearly as a potential threat in the rear.

The spokesman for Lega, one of Italy’s two ruling parties, financial economist Claudio Borghi, has said that his party wants to introduce a parallel currency, the so-called mini-bots, to solve Italy’s financial problems. According to him, these are small government papers that are transferable, denominated in euros and circulated as paper money. Since you can pay your taxes with the mini-bots for the printed euro amount, they are probably only traded at a small discount on real euros. Italy hopes to use the mini-bots to pay off part of its national debt.

Paolo Savona, Minister of Europe for the new government, goes even further. In 2015 he formulated the strategy of a euro exit in great detail. Savona’s plan, however, had the problem that it didn’t know how to solve the problem of physical banknote printing without the capital markets getting wind of it.

The mini-bots are apparently supposed to solve this problem. Since they are introduced before the exit, they are already there when the currency changeover is suddenly perfected on a weekend. All bank accounts, all employment and rental contracts and all internal credit contracts are retained in principle, only the euro symbol is replaced by a lira symbol. Savona also plans to convert the government debt it had issued before 2012 into lire. That is still three quarters of all outstanding paper today. In addition, there should be open haircuts to further reduce government debt. The Banca d’Italia’s TARGET debt to the Eurosystem is to be canceled. This could even happen because there is no legal basis for paying them after the euro has been got rid off and because leading German politicians have long described them as “irrelevant clearing balances”. Everything is of course to be kept secret until the last second to prevent capital flight.

Europe will have to give Italy a lot of money to avert all of this. Either way, the next act of Euro-Italian tragedy begins.

*First published in the German newspaper “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung”. Tranlation into English by Yuri Kofner. Source: https://www.hanswernersinn.de/de/die-italienische-tragoedie-fas-18112018

**Translated and republished without prior written consent. For educational purposes only.