_ Johannes von Möllendorff, Master (Economics), Universität St. Gallen. Translated into English by Yuri Kofner. 11 September 2020.

Why does a sovereign debt crisis almost always go hand in hand with a deteriorating economic situation? This article explains how national debt that is perceived as being too high increases the financing costs of banks and, in response, puts the real economy in distress with restricted lending.

The economists Marcello Bofondi, Luisa Carpinelli, and Enrico Sette (2018) from Banca d’Italia investigate how the 2011 sovereign debt crisis affected bank lending in Italy. They look at both lending rates and loan volume growth and compare the lending of Italian banks with that of subsidiaries and branches of foreign banks in Italy. Their idea is that the financing costs of banks headquartered in Italy will increase due to the sovereign debt crisis because they hold large amounts of domestic government bonds, which investors perceive as a higher risk. Banks from countries in which there was no sovereign debt crisis, on the other hand, should not feel any increase in financing costs.

Study based on the 2011 national debt crisis in Italy

For the crisis year 2011, the research group used data from the Italian credit register, which records all bank loans to Italian companies. They differentiate between a pre-crisis period (January – June) and a crisis period (July – December). The data set includes a good 664,000 bank-customer relationships, around a quarter of which are with foreign banks. The study takes into account a total of 567 banks, 49 of which are foreign. Banks from France, Germany, the USA, and Austria are most strongly represented.

First, the researchers measure the change in the financing costs of the Italian state compared to a risk-free interest rate, using German government bonds as a reference. The spreads on Italian government bonds rose sharply from July to December 2011 from around two to around five percent. In contrast, in the four countries mentioned, from which most of the foreign banks come, the interest rate premiums did not increase or increased only slightly during the crisis.

The borrowers work in the services (approx. 50 percent), industry and energy generation (approx. 30 percent), construction (approx. 12 percent) and agriculture (approx. 8 percent) sectors. In their analysis, the three economists only record those companies that had taken out loans from both an Italian and a foreign bank. They also take into account differences between banks (e.g. size, profitability) and between companies. In addition, they focus on particularities in the relationship between the bank and customers, such as B. the duration of the customer relationship or the share of the loans granted by a certain bank in the total loan volume of a company. This enables the researchers to rule out systematic differences that could distort the effect of the sovereign debt crisis.

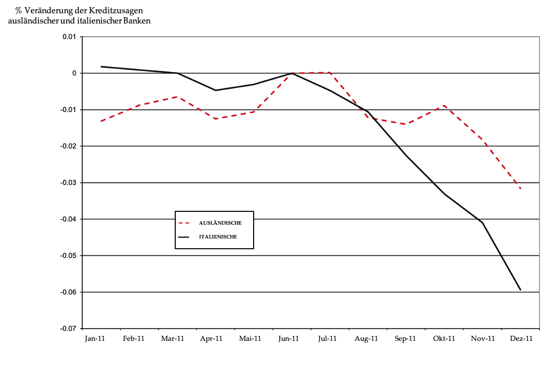

The research team analyzes the credit growth of Italian and foreign banks. Figure 1 shows that credit growth was similar until the outbreak of the crisis in June 2011 and hardly declined. After that, however, the lending growth of Italian banks declined sharply, while the foreign banks reduced lending only with a delay and much less.

Figure 1: Credit growth of domestic and foreign banks in Italy

Source: Bofondi et al. (2018)

Italian banks suffered from risky government bonds in their portfolio

The researchers’ estimates confirm this connection. The credit growth of foreign banks during the crisis was around three percentage points higher than that of domestic banks. Taking other factors into account, such as customer relationships between banks and companies, the difference in loan growth was still 1.7 percentage points. Both results are economically significant, as lending fell by an average of 6.6 percent during the crisis.

To confirm their results, the research team used, among other things, a data set that includes only the 50 largest Italian banks alongside foreign ones. These two groups of banks are particularly comparable and differ mainly in their holdings of Italian government bonds. The quantitative results were also confirmed in this data set.

Foreign banks are represented in Italy either with independent subsidiaries or with branches. Subsidiaries are very similar to Italian banks in terms of business model and network, while branches are only active in certain regions and market segments. Does the organizational form of foreign banks influence their lending during the crisis? The results show that this aspect played an important role: lending differed greatly between Italian banks and the subsidiaries of foreign banks. The latter granted significantly more loans during the crisis. Banks that were only represented by dependent branches behaved similarly to Italian banks.

Can a credit crunch be avoided with loans from foreign institutions?

To what extent have companies been able to compensate for the reduced supply of credit from Italian banks with additional loans from foreign banks? The results are extremely meaningful. Firms that financed themselves with foreign banks showed higher credit growth. A company that financed itself more from foreign banks before the crisis (by 23 percentage points) was able to increase its credit growth by 0.8 percentage points during the crisis, compared to companies that were more dependent on Italian banks. This effect is all the more significant given that lending fell by an average of 3.8 percent during the crisis. Overall, Italian companies were only partially able to compensate for the lower lending by Italian banks with loans from foreign banks.

In a final step, the researchers examined how the sovereign debt crisis in Italy affected lending rates. If the value of government bonds falls, the banks will have to digest heavy losses, but not their foreign competitors from safe countries. The results show that during the crisis foreign banks demanded 0.21 percentage points less for short-term overdrafts and 0.15 percentage points for long-term loans in Italy than domestic banks.

The present study uses Italy as an example to illustrate how a sovereign debt crisis can infect the banking sector, as a result of which lending by domestic banks is reduced, lending rates rise, and thus hit the real economy. Companies can only partially compensate for this by borrowing more from foreign banks.

Literature:

Bofondi, Marcello, Luisa Carpinelli und Enrico Sette (2018), Credit Supply During a Sovereign Debt Crisis, Journal of the European Economic Association 16, 696-729.

Source: https://www.oekonomenstimme.org/