_ Claudius Gräbner, Jakob Hafele, ZOE. Institut für zukunftsfähige Ökonomien. Bonn, August 2020. Republished from the original paper with some chapters and the literature list omitted.

This paper investigates the emergence of polarisation patterns in the EU during the last 60 years from a structuralist and complexity economics perspective. Based on the results, feasible opportunities for EU policy-making, which aim to counteract a tendency of polarization, are delineated. The study comprises of a historical analysis of the politico-economic events during this time and complementary quantitative analysis of the European trade network.

The results suggest that trade in the Eurozone is unequal at the expense of the peripheries and follows a pattern of “unequal technological exchange”.

The paper also assesses the usefulness of country taxonomies such as ‘cores’ and ‘peripheries’ for identifying the roots of polarization patterns. While it generally affirms the relevance of structural dependencies, and confirms the epistemic usefulness of country taxonomies, it also highlights three challenges – the challenges of dynamics, of ambiguity and granularity – that any such taxonomy necessarily faces, and which must be dealt with explicitly in any structuralist analysis using such taxonomies.

Introduction

This paper studies polarisation patterns in the EU during the last 60 years from a structuralist perspective. It pursues two goals, one substantial, the other methodological: first, it seeks to contribute to a better understanding of the historical roots of polarization patterns in the EU and to delineate pragmatic and feasible policy measures that can be used to counteract current polarization patterns. Second, existing structuralist studies regularly use country taxonomies, such as ‘cores’ and ‘peripheries’ in their analysis, and then try to identify structural interdependencies between the groups. Grouping countries always comes with a loss of information and a certain degree of ambiguity. Therefore, the second goal of this paper is to ask critically to what extent the analytic gain of using such country taxonomies outweights their potential costs of shallowing the particularities of single countries. Political and economic polarization patterns in the EU have been documented by several recent studies (e.g. Celi et al., 2018; Gräbner et al., 2019, 2020b; Simonazzi et al., 2013). The reasons for these patterns remain, however, subject to debate. While some prominent explanations consider the financial crises in 2008_ as a major source for these polarization patterns, others stress that polarization has its roots in the decade before the financial crisis (e.g. Gräbner et al., 2020b). The present contribution goes back in time even further: inspired by structuralist theorists such as Musto (1981) – who warned already in 1981 that “growing inequalities, caused by regional concentration of economic activities, will lead to permanent structural crisis in the Union, predetermine the development outlook of the new [Southern] member states and hinder further integration” (p. 245, translation by the authors) – it searches for deeper structural reasons of ongoing polarization dynamics in the whole time period since the 1960s. Considering such longer time horizon also allows for a critical evaluation of the dynamics of core-periphery structures with regard to the actors involved: as will be shown below, although the core-periphery structure as such can be observed over almost the entire time frame since the 1960s, the allocation of countries to the core and the periphery as such is not entirely stable. An adequate consideration of such longer-term phenomena is important in the context of the second main focus of the paper, i.e. the critical evaluation of a structuralist approach to study polarization in the EU.

Before we proceed, two methodological clarifications are in order: first, the present paper rests upon the triangulation of two non-standard approaches to socio-economic development: structuralism and economic complexity. The two approaches are complementary since complexity economics provides for a number of methods that can be used to study patterns – which have been described by structuralists many years ago – quantitatively and in more depth. At the same time, structuralism can provide for a theoretical framework that most current complexity economic studies are lacking. By contextualizing the quantitative part of the investigation, the two approaches are triangulated in a way that is consistent with a critical realist perspective (Lawson, 1997). Second, since approaches are also characterized by a focus on the productive sphere of the economy and for the pragmatic reason of data availability, most of the discussion that follows focuses on economic development and polarization in the manufacturing sector. This can be justified by the structuralist contention that the industrial sector of a nation is crucial for its overall development since it not only provides for accessible employment opportunities for both skilled and unskilled labor, but is also essential for the di_usion of productive knowledge within the economy.

…

The paper proceeds as follows: the paper adopts as a baseline taxonomy the classification proposed in Gräbner et al. (2019) with the only exception being France, which is – because of its political power (Schneider, 2017) – considered a core country in the present paper2.

The resulting taxonomy is summarised in table 2. This taxonomy is not only based on both theoretical and empirical considerations, it also represents a workable compromise between aggregation of similar countries into meaningful groups, and suffcient granularity to account for

specifics. Moreover, the typology is based on a perspective on the current situation in Europe. Therefore, the historical analysis in section 3 allows for a critical analysis of how countries arrived at their current place in this typology and, because of the long time horizon covered, allows for a critical reflection of the taxonomy, particularly against the three challenges mentioned above.

Before proceeding with the historical analysis, the classification of one country deserves further justification: Considering Italy as part of the periphery is certainly a controversial choice, which provides for an immediate illustration of the three challenges introduced above. First, as will be shown below, Italy is subject to the challenge of dynamics since it cannot be considered to be part of the European periphery right from the 1950s. Second, Italy illustrates the challenge of ambiguity, since it is politically quite influential in Europe and the world: it is part of the G7 and has an influential voice within European policy debates. However, there are also reasons for the classification of Italy as periphery country: not only is it struggling with low productivity, but it also plagued with high levels of public debt and relatively high unemployment rates. Thus, in economic terms, Italy shares more with countries typically associated with the periphery. And also the political position within Europe might not be as strong as the size and the history of the country might suggest. As the current debate about the introduction of European bonds, particularly during the Covid19-pandemics (‘Corona-Bonds’) shows, Italy cannot enforce their interests effectively against Germany and other Northern European countries. Finally, Italy also illustrates the challenge of granularity. Some parts of Italy, particularly in the North-West, host very productive, highly innovative and internationally competitive industries and are characterised by low unemployment and high incomes. At the same time, other areas, particularly the Southern ‘Mezzogiorno’ are lagging economically, suffering from high unemployment and technologically inferior businesses. Thus, there are cores within the periphery, just as there are some peripheries within the countries classified as cores (some parts of Eastern Germany immediately come to mind).

Developmental trends in Europe since 1950

The structuralist contributions reviewed in the preceding section suggest that unequally distributed technological capabilities, as well as the asymmetric power relations between core and periphery countries, play an important role for current polarization dynamics. Since they also stress the relevance of path dependencies inherent in the politico-economic environment, the present exposition takes a long-term perspective starting from 1950s.

Catching-up after the second World War

The 1950s and 1960s were, at first sight, a time when today’s periphery countries experienced good economic development: the industrial sectors in the Southern European peripheries were growing steadily, supported by the protectionist policies in place (Foreman-Peck and Federico, 1999).

In effect, the peripheries showed considerable growth rates. For example, in the 1960s Greece experienced the 2nd highest average growth rate worldwide, exceeded only by Japan (data: World Bank). However, because of their backlog in terms of technological capabilities, the European peripheries remained dependent on capital and technology imports from the core – a situation that structuralists describe as ‘dependent industrialization’ (e.g. Nohlen and Schultze, 1985).

According to Becker et al. (2015) this led to current account deficits financed by tourism and remittances from the core countries – a highly dependent development model making the peripheries vulnerable to crises.

The time after the second World War also provides for a first example for the challenge of dynamics. Italy, in most of the core-periphery literature treated as a periphery, was at this point of time much closer to the core: it industrialized earlier than Greece, Spain and Portugal and, consequently, had a much stronger industrial base in the 1960s than the other countries. Thus, it also enjoyed a considerably higher standard of living (Simonazzi and Ginzburg, 2015). Until about 1962, the Italian economy also experienced further industrialisation and upgrading, fuelled by protective and active policies and quick urbanisation (Celi et al., 2018).

France on the other hand, often treated as core country because of its considerable political power and its high GDP (Seers, 1979) has shown a negative trade balance throughout the 1960s and 1970s (data: COMTRADE) and lagged behind in terms of size and complexity of its industries. Since its political position was already very strong at that time, it also represents an example for the challenge of ambiguity at that time. This indicates that countries may switch positions within a given taxonomy and begs the question about the determinants of such changes – a question that will be taken up below.

Economic liberalization, increased competition and the end of convergence in the 1970s and 1980s

The Treaty of Rome set the stage for an ongoing process of economic liberalization which culminated in the integration of Greece, Portugal and Spain into the European single market in 1981 and 1986, respectively. The rules of the Single Market were applied to all countries equally – to the economically and technologically strong core countries as well as the economically and technologically less developed peripheral countries (see table 2). The integration of Greece, Portugal and Spain into the Single Market led to increasing imports from the technologically strong core countries. These flows of manufactured goods from the core into the periphery followed the liberalization and put the previously well-protected industries in the periphery under increased competitive pressure. There are a number of arguments for why the industries in the peripheries were not ready for this increasing competition:

- their lower productivity as compared with the firms in core countries (Hummen, 1977; Musto, 1986; Seers, 1979),

- their smaller size and inability to exploit economies of scale (firms in the peripheries were much smaller, handicraft type of manufacturing, as compared to the large industrial plants in the cores Hummen, 1977; Zouboulidis, 2006),

- their low innovativeness (Seers, 1979; Simonazzi and Ginzburg, 2015), and

- less linkages with other industries and related services (Simonazzi and Ginzburg, 2015; Zouboulidis, 2006).

The shift of policies towards integrated markets was not an isolated European phenomenon. The replacement of Keynesian polices with market-liberal policies in the 1970s led to an increasing globalization of manufacturing structures and the rapid growth of global production networks (Dicken, 2015). This change was accompanied by a centralization of worldwide industrial production into fewer and larger firms and thus also an accumulation of power in these production networks (Dicken, 2015; Kapeller and Gräbner, 2020).

So-called lead firms, which often resemble an oligopoly within the production network, faced smaller suppliers who were exposed to increased competition. This asymmetrical structure allowed lead firms to decide what, when, how and where to produce and to exert price pressure on the suppliers creating a new kind of dependency of firms that were integrated into those networks as suppliers (Milberg and Winkler, 2013, p. 111, 123.). This shift was accompanied by increasing demand for complex and high-quality goods in European core-countries, based on the saturation of those markets with durable consumer goods (Simonazzi and Ginzburg, 2015, p. 112). Companies responded with vertical product differentiation, shortened product cycles and services-based marketing strategies. Thus, more complex and higher-quality products were created, which were integrated into a marketing-oriented service sector making it more dicult to compete with.

For the European peripheries it became much more difficult to produce competitively with core-countries industries because the shift towards more complex products meant that tacit productive knowledge, sectoral linkages and broad production networks became relatively more important as main determinants for international competitiveness (e.g. Carlin et al., 2001; Dosi et al., 2015). These demands could only be met by very few of the most productive firms in the peripheries.

The oil crisis in the 1970s came on top of the increased competition stemming both from the EU market liberalization and the globalization of production structures. Those two e

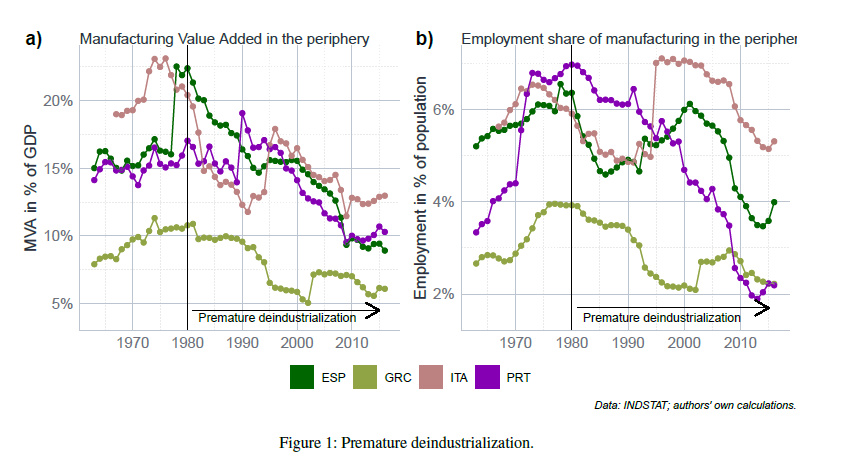

ects led to the exit of smaller and younger industries in the peripheries. Figure 1 shows that the share of manufacturing value added (MVA) in GDP started to decline, even before the countries had gone trough a proper experience of industrialization, given rise to a ‘premature de-industrialization’ (Rodrik, 2016).

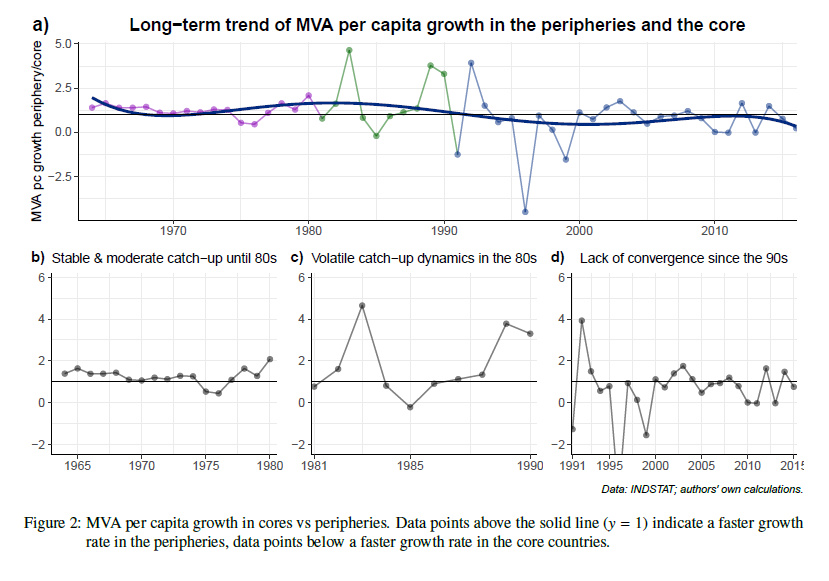

This premature de-industrialization marked a turning point in the catch-up process of the European peripheries. A phase of broad and rapid industrialization was interrupted and replaced by a phase in which only the most productive industries survived, mostly by being integrated into global production networks. This led to a new type of dependent development in which peripheral economies became depended on lead-firms in global production networks. Figure 2 depicts the stable catch-up process until the oil-crises, which then became volatile and finally stopped.3

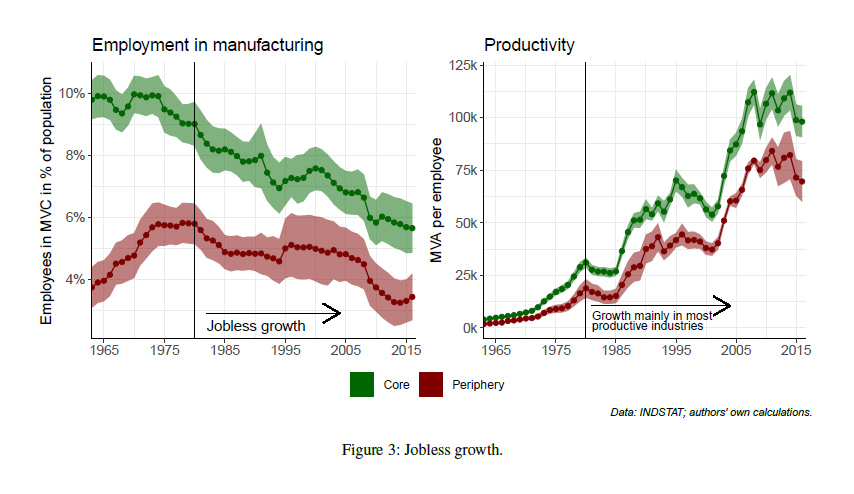

The globalization of production structures helped those firms that were placed close to international hubs. Supported by the industrial agglomeration policies of the time this led to the development of ‘cores within the peripheries’ creating an uneven development pattern within the peripheries (Simonazzi and Ginzburg, 2015; Stoehr, 1985; Weissenbacher, 2015).4 Moreover, from the 1980s on, industrial development in the peripheries was almost entirely led by productivity increases, i.e. the phase of MVA growth after the 1980s was mostly jobless (see figure 3). So, huge parts of the peripheral population didn’t benefit directly from the remaining industries anymore. In all, the decreasing importance of industries in the peripheries during this period marked the end of their industry driven growth-model.

This period, again, contains a number of examples for the challenges for country taxonomies introduced in section 2.2: first, with regard to the challenge of dynamics, we have seen that Italy has started o_ as a relatively well-industrialized country in the 60s and could well be classified as a core country. After the 80s this advantage, however, has vanished to a large extent, so it presents itself more as a member of the periphery. Among the events that were crucial for Italy’s decline into the periphery were the 1963 crisis caused by the excessive monetary expansion and resulting needs for contractions. In context of the oil crisis5 and combined with increasing imports resulting from free-trade agreements in the EC and the failure to improve the productive structures in the South fast enough this led to premature deindustrialization (Celi et al., 2018, p. 224-228). Second, the challenge of granularity becomes particularly relevant due to the phenomenon of ‘centres within the peripheries’ (see above): in countries such as Italy or Spain, regions with surviving industrial clusters one would find many characteristics of core regions, yet this is in stark contrast to most of the other regions in these countries. Finally, also the challenge of ambiguity presents itself in a very pronounced fashion during this time: France, one of the politically most powerful countries in Europe, su_ered from some characteristics more typical to a peripheral economy. The world market integration in the 1960s and 1970s led to a continuous trade balance deficit and together with the oil crises in the 1970s it put a stop to its rapid industrialization process from which it didn’t recover until the 1990s (Data: Worldbank).

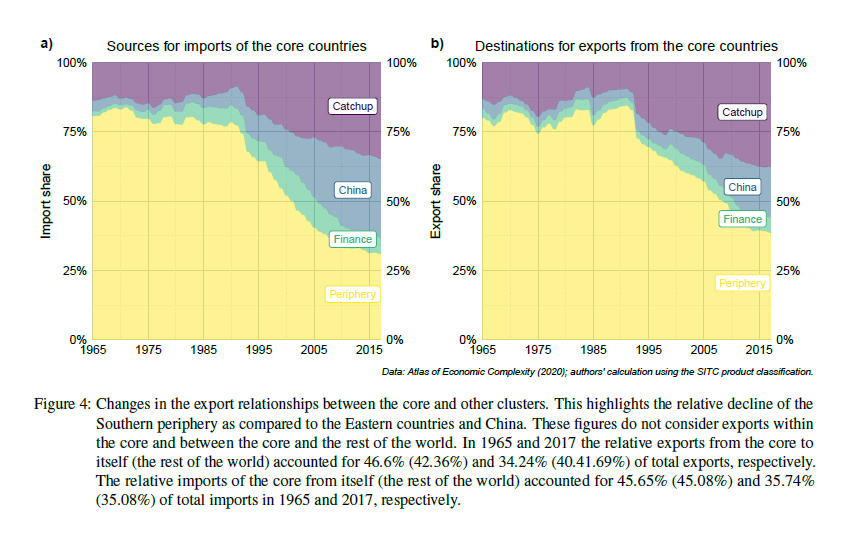

Four further events were important for the accelerating polarization patterns in Europe: (1) the Eastern enlargement, (2) financialization, (3) the financial crisis as well as (4) the increasing race for the best location within Europe. During the eastern enlargement of the EU between 2007 and 2013 several countries entered the EU, which do not fit neatly to the dualist distinction between a ‘core’ and a ‘periphery’: recent studies suggest to treat them as a separate country groups (e.g. Gräbner et al., 2019) and even stress differences among Eastern European countries themselfes (see e.g. Bohle, 2017; Celi et al., 2018).6 The fundamental differences of the Eastern to other European countries are not surprising given the particular historical circumstances in which most Eastern European countries entered the EU in the 1990s: those eastern countries had just gone trough deep transformation crises following the disintegration of the Soviet Union and of former Yugoslavia. Moreover, the integration process into the EU induced further institutional changes due to the conditionality of the process, which included the need for the liberalization of capital movements and suggested privatizations (Bohle, 2017). The liberalization of goods and financial markets led to deindustrialization and high unemployment in a first phase, and the subsequent establishment of a low-wage sector which fitted into European supply chains in a second phase (Becker et al., 2016) . This way, the Eastern enlargement had profound effects on the Southern periphery since low-cost producers in the East started to displace exports from the South, indicating a replacement of imports from the South through imports from the East, particularly in sectors related to the German manufacturing core (Celi et al., 2018, see figure 4). Thus, the Eastern enlargement is, thereby, again an illustration of the structuralist argument according to which peripheries and centres are affected differently by general events. In the present case, while countries in the core benefited from the new low-wage labor markets in the East, countries in the periphery suffered from the increase in competition.

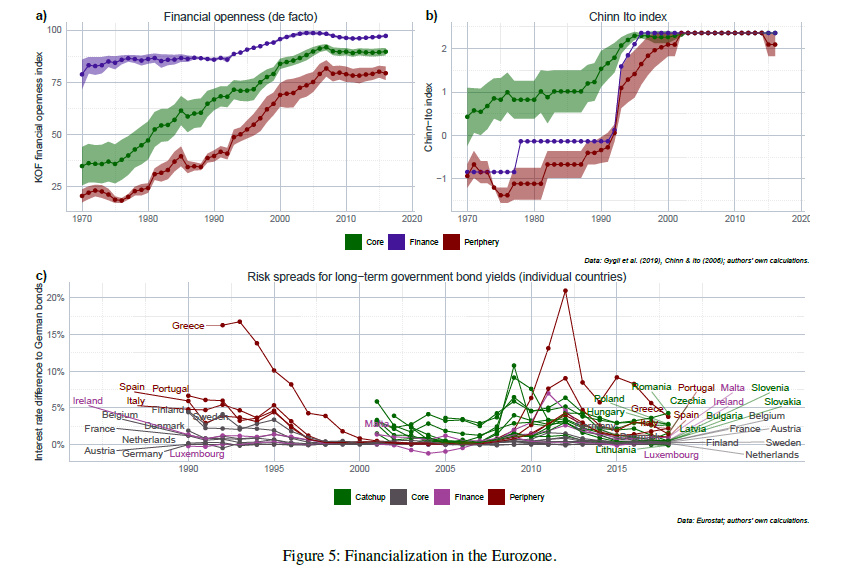

The second major event is related to the liberalization of financial markets in the 1990s and 2000s. Financial goods became increasingly important and a shift in economic rationale towards financial motives followed. The process of the increasing importance of the financial sector is commonly termed ‘financialization’ and had a profound impact on the Southern peripheries, particularly by facilitating speculative bubbles (for more details see p. 234_ in Celi et al., 2018).

Important hallmarks for the financialization process in the EU were the lifting of capital controls in the 1990s, the deregulation of interest rates (1993), the two banking directives on the harmonisation of the banking market (1981 and 1992) and the adoption of the 1999 Five-Year Financial Services Action Plan. Parallel to this process, the introduction of the Euro eliminated exchange rate risks and – together with the financial market deregulation – ultimately led to a fully integrated and liberalised European financial market, which caused a convergence of interest rates, risk assessments and an increase in cross-border capital transfers within the euro area (Caldentey and Vernengo, 2012, see figure 5).

In the southern European peripheries this new conditions gave rise to a new, debt-led growth-model with the notable exception of northern Spain in which solid industrial development was established. For the rest of Spain and the other Peripheries this new growth-model replaced the period of growth mostly based on industrialization in the 1960s and 1970s: The convergence of interest rates and risk assessments has greatly improved credit conditions for these countries. After a phase of stagnant economic development in the 1980s these favourable credit conditions made it possible for households to increase consumer spending based on debt (Caldentey and Vernengo, 2012). Most notably in Greece and Portugal, the poorest of the southern European peripheries, this led to a “consumer society without a production base” (Fotopoulos, 1992, from Simonazzi and Ginzburg 2015, p. 125). Large amounts of capital also flowed into the real estate sector, which led, especially in Spain, to a sharp rise in prices and later to a real estate bubble. (Becker et al., 2015).

In face of the fact that the euro made currency devaluation an impossibility and the limitations for active industrial policy imposed by the Lisbon treaty the options to supporting catching-up industrialization by economic policy where limited (e.g. Celi et al., 2018). In this situation, politicians increasingly relied on the tourism sector as a growth driver. Credit-financed growth in the consumer, real estate and tourism sectors of the peripheries were the consequence (Celi et al., 2018, p. 86). At the same time, with the exception of northern Spain, the development of the production base stagnated. Thus, the process of financialization also provides for a further illustration of the structuralist argument that the polarization between cores and peripheries gets reproduced by their di_erent reaction to general events: in this case, the financialization impacted upon di_erent European economies very distinctively. This also applies to the financial crisis in 2007_: while the elaborations so far show that the crisis is as such not the reason for the current polarization patterns, it worked as an accelerator: countries in the periphery were hit asymmetrically hard because their growth models – which were mainly debt driven (see e.g. Gräbner et al., 2020b) – were rendered unfeasible through the crisis and the policital reactions in the form of austerity. Since these countries have not been able to substitute the falling domestic demand with rising exports, due to the technological inferiority of the majority of their firms, they were hit hard by a recession, which was much less severe for the technologically advanced countries in the core (Gräbner et al., 2020b).

Finally, core-periphery relationships were aggravated through the increasing level of competition among European countries (‘European race for the best locations’, see Kapeller et al., 2019). Given the current institutional framework, countries were incentivized to improve upon their relative competitiveness via particular location factors, if necessary at the expense of other European countries. In Germany and most other countries of the core these location factors could be provided by their technological capabilities (Gräbner et al., 2019, 2020b; Kapeller et al., 2019). The accumulation of such capabilities is a path dependent process in which countries with already many capabilities usually are enabled to accumulate even more capabilities faster, leading to a situation in which “success breeds further success and failure begets more failure” (Kaldor, 1980, p. 88).

Some other countries, especially those that entered the EU during the phase of the Eastern enlargement were not able to compete with the core countries in terms of their technological capabilities, but given their historical circumstances it was easy for them to o_er low wages as an alternative location factor (Gräbner et al., 2019). This strategy was, for historical and institutional reasons, not feasible in countries in the European South, such as Italy, Spain or Portugal. The financialization patterns described above allowed for another way to create favorable location factors: countries such as Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands or Malta attracted companies and wealthy companies and individuals with a ‘competitive regulatory framework’, which allowed these players to save taxes and evade regulations in other European countries. Ireland, for instance, provides favorable conditions for multinationals, particularly in the pharmaceutical and chemical industries (see, e.g., Barry and Bergin, 2012) and Luxembourg competes with low tax rates for wealth and swift financial services (e.g. Zucman, 2015) These strategies are typical examples for ‘beggar-thy-neighbor’ policies, which improve the situation of one country at the expense of others. With regard to the tax strategy of the Netherlands, Cobham and Garcia-Bernardo (2020) estimate that European member states lost in total 10-15 billion of corporate tax, with the corresponding corporate tax collected in the Netherlands amounting to only about 2 billion Euros. Three of the five by far most a_ected countries belong to the periphery: France, Italy, and Spain lost about 2.7, 1.5 and 0.9 billions of corporate taxes due to the Netherlands (Cobham and Garcia-Bernardo, 2020).7 Thus, the ‘race for the best polarization patterns in Europe and thereby a stabilizer for the core-periphery demarcation within the EU. In all, the historical elaborations so far suggest that today’s polarization processes have their roots in the longer-run dynamics in the EU. This is consistent with early prediction of structuralist scholars such as Musto (1981). The next section complements these structuralist observations with new forms of evidence on the trade flows on the product level between European countries for the time period considered.

Unequal technological exchange in the EU trade network

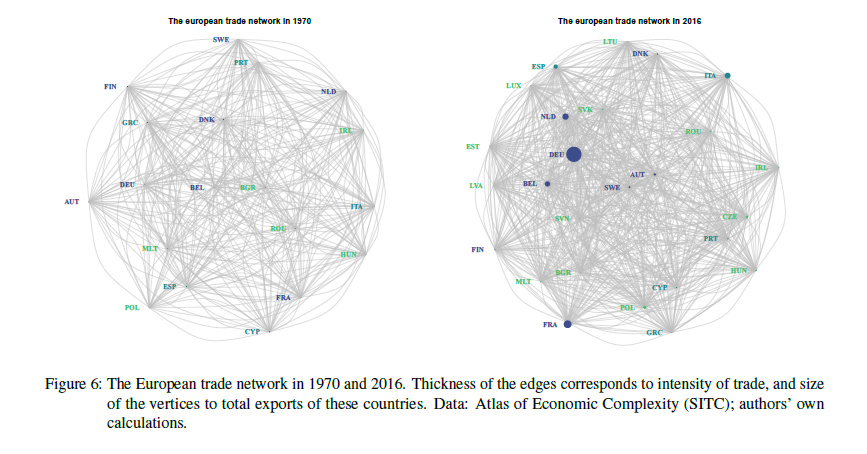

The previous elaborations stressed the relevance of the industrial sector for economic development and polarization dynamics. This section complements the analysis so far by highlighting another dimension of self-reinforcing coreperiphery relations in the European trade data (for a visualization see figure 6). To this end, we study data on intra- European trade flows on the product level. These data has considerable advantages over ‘simple’ macro data such as such as GDP and industrialization shares, which contains only limited information about production structures and no information about the relationships and dependencies across countries – the latter being crucial for a structuralist analysis. At the same time, there are undeniable drawbacks such as the inability to identify outsourcing activity and exploitative value added chain structures. To consider such information one would need to use value-added-trade data, which would come with considerable disadvantages in itself, such as its dependency on the assumptions made during its construction and its limited availability. Thus, while a valuechain- analysis in the spirit of Caliendo et al. (2017) would add considerably to the topic at hand, one has to acknowledge that not only does such analysis come with its own fundamental drawbacks, it is certainly beyond the scope of the present paper.

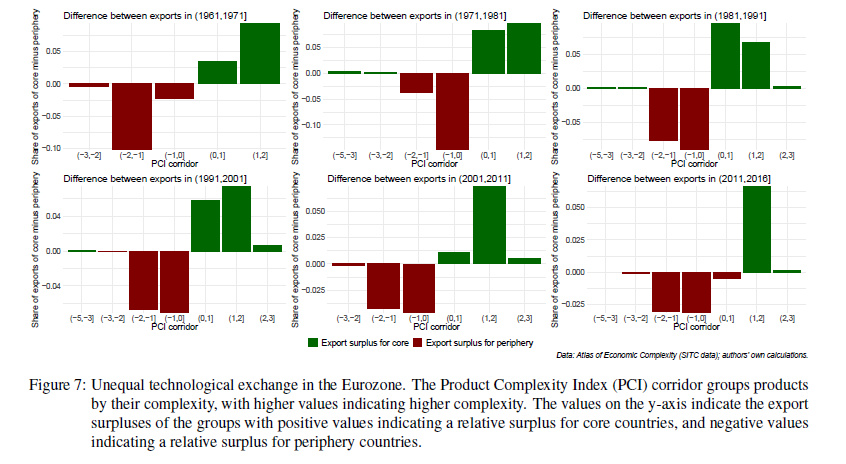

That being said, the network-theoretic analysis of trade data helps us to highlight a dimension of polarization in Europe that has so far received little attention in the literature: that of an ‘unequal technological exchange’.

The concept of an ‘unequal exchange’ has a long tradition in structuralist thought, dating back to the original hypothesis of Prebisch (1950) and Singer (1975) (see also section 2). They argued that the exchange of agricultural goods from the periphery to the core and of industrial goods from the of the periphery. As can be seen from figure 7, a variant of such unequal exchange relationship can be observed for the Eurozone. Only this time it is not about agricultural and industrial, but about simple and complex products: one can observe that countries from the periphery export less complex products to the core, while the core countries export more complex products to the periphery. This suggests the existence of a ‘vicious specialization’ in Europe: the core countries have specialized in the production of complex products, i.e. an activity that has been found to be one key driver to economic prosperity (Hidalgo and Hausmann, 2009; Hidalgo et al., 2007), while the periphery countries serve as workbenches for less attractive goods. This finding aligns well with Gräbner et al. (2019), who find that trends in sectorial specialization in Europe happened at the expense of Southern European countries. The present analysis provides additional evidence from European network data.

This is an example where the tools of complexity economics help highlighting yet another dimension of the unequal relationships between cores and peripheries as previously theorized by structuralist thinkers. The resulting concept of an ‘unequal technological exchange’ aligns well to core-periphery thinking as outlined above and, as will be discussed in the next section, has some immediate implications for policy.

Discussion

5.1 Core-periphery structures in the EU One goal of the present paper was to contribute to a better understanding of the historical roots of polarization patterns in the EU from a structuralist perspective, while at the same time providing a critical self-reflection on the analytical usefulness of structuralist country taxonomies. In this context, the paper highlights a number of issues that are also relevant for the delineation of policy measures against polarization patterns:

First, the history of Europe is not exclusively a history of polarization. There were periods – albeit brief – without a drifting-apart between country groups and in which countries in the periphery showed some signs of actual catchingup. These periods, however, were short and fall into the time before the focus on trade liberalization in the EU. Second, the literature and the present paper discuss several events and phenomena that can be considered reasons for polarization, such as financialization, the 2007 crisis or inter-European competition. The long-term perspective of section 3 suggests, however, that many of these alleged reasons are accelerators rather than ultimate causes for polarization: a divergence of production structures and asymmetric trade relations in the form of unequal technological exchange have been visible well before the Eastern Enlargement, the financial crisis, or the emergence of a financialized growth model. While this is not to deny the important role of these events in substantially accelerating polarization, it does suggest to also ask for deeper reasons of polarization and for ways to eliminate these ultimate sources via adequate policy measures.

Third, section 2.3 introduced three challenges for structuralist country classification: the challenges of dynamics, ambiguity and granularity. Throughout the historical view on the developments in Europe on encounters numerous examples for the relevance of each of these challenges. Italy, for instance, has moved from the group of core countries in the 50s to the periphery, illustrating the challenge of dynamics. France is a country that holds both characteristics of a core country (e.g. influential political position), as well as a member of the periphery (e.g. high unemployment and vulnerable labour markets), thereby illustrating the challenge of ambiguity. And Spain with its ’cores within the periphery’ does the same for the challenge of granularity: regions in the North are economically extremely well-o

and competitive, while much of the remaining countries is facing serious economic problems. This suggests that country classifications have to be used carefully and the criteria for the classification must be made very explicit. Moreover, one must keep in mind that heterogeneity both within country groups as well as within countries might be considerable and that despite path dependencies it is not impossible for countries to switch to an alternative development trajectory, catapulting them into a different group.

Fourth, despite the relevance of the three challenges just described, the country classifications are relatively stable and changes between groups can happen only in particular windows of opportunity (or ‘critical junctures’ Capoccia and Kelemen, 2007). Therefore, adopting a core-periphery view on the developments in Europe not only helps to highlight these exceptionable events, but also facilitates the identification of important structural features of polarization patterns in Europe. Particularly, a historical view shows that countries on different development trajectories can be affected very differently by the very same historical event, and that institutional changes in the Union, although affecting all countries equally in the first place, do not necessarily have the same consequences for all countries (on a similar point regarding institutions more general see Chang, 2010).

Fifth, the structuralist perspective on core-periphery relations is distinctively useful when compared to other research programs also using a core-periphery categorisation (see section 2): ‘cores’ and ‘peripheries’ in Europe are not merely a result of different endowments, policies and institutions as considered in the fields of New Trade Theory, New Economic Geography or the Varietes of Capitalism approach. Rather, the relationships among ‘cores’ and ‘peripheries’ reproduce the groups themselves and must not be neglected when designing policy measures meant to end polarisation in Europe.

Finally, the simultaneous relevance of the challenges as well as the usefulness of structuralist country classifications and the focus between groups suggests that relationships between countries on different trajectories are an important, yet one among several explanatory elements to make sense of polarisation. As often the case in economics, a plurality of approaches is necessary to fully understand a given phenomenon. The single approach, illuminating as it is, will always suffer from certain blind spots, which can only be eradicated by a pluralist research endeavour transcending a single study.

Tables and figures

Source: https://zoe-institut.de/