_ Yuri Kofner, junior economist, MIWI – Institute for Market Integration and Economic Policy; Nomuun Khaliun, officer, Investment Research Centre, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mongolia, Masters in “Renewable energy and Governance”. Munich – Ulaanbaatar, 8 October 2020.

Stylized facts about Mongolia’s economic and trade development

For the past five years, Mongolian economy has struggled with falling commodity prices in the extractive sector and a sharp increase in public spending on loans due to an overly optimistic forecast of revenues from the development of large mining deposits.

In 2015 the country’s annual GDP growth rate reached 2.4 percent. In 2016, GDP growth diminished by 1 percent, the primary fiscal deficit reached 12.5 percent of GDP. In line with the “Action Plan of the Government of Mongolia 2016-2020”, measures were taken to revive the economy by gradually reducing the budget deficit. As a result, economic growth intensified again in 2017, reaching 5.3 percent. The growth continued in 2018 as well and the GDP grew by 6.9 percent. In 2019 the GDP growth rate reduced slightly reaching 5.1 percent.

The overall amelioration of the economic situation was facilitated by an increase in income from foreign trade. According to the Observatory of Economic Complexity, in 2018 the top exports of Mongolia were coal briquettes (USD 2.8 bln), copper ore (USD 2.01 bln), gold (USD 870 mln), crude petroleum (USD 391 mln), and iron ore (USD 342 mln). The top imports to Mongolia were refined petroleum (USD 1 bln), cars (USD 400 mln) and trucks (USD 251 mln), electricity (USD 143 mln), and large construction vehicles (USD 125 mln).

As of 2018, Mongolia traded with 159 countries. Overall, it exported USD 7.7 bln and imported USD 5.8 bln, resulting in a positive trade balance of almost 2 bln. I

Mongolia exports mostly to China (USD 6.4B), Switzerland (USD 727 mln), the United Kingdom (USD 173 mln), Russia (USD 84.9 mln), and Italy (USD 73.7 mln), and imports mostly from China (USD 1.i bln), Russia (USD 1.6 bln), Japan (USD 540 mln), South Korea (USD 308 mln), and the United States (USD 177 mln).

In the aforementioned “Action Plan of Government of Mongolia 2016-2020” specific attention was paid to the diversification of export products so that the economy will not be that sensitive to the fluctuation of the global commodity prices.

As a landlocked country with a relatively small economy (the number 133 economy in the world in terms of GDP in current USD), Mongolia faces a variety of complex problems to overcome. It is difficult for Mongolian goods to stay competitive and reachable due to the country’s physical and economic “isolation”. So far, Mongolia has managed to conclude a free trade agreement and economic partnership agreement only with Japan (2016).

So for this reason, it is a matter of urgency for Mongolia to primarily integrate into the regional economic cooperation process to be able to gain access to the world market. Moreover, Mongolia is in need to establish free trade with countries or unions with a strong economic performance.

Stylized facts about Mongolia-EAEU trade and economic relations

For Ulaanbaatar, a promising free trade agreement could be with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).

The Eurasian Economic Union, founded in 2015 by the five post-Soviet states Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia, is a supranational trade and economic bloc with the aim of creating a common internal market based on the free movement of goods, services, labor, capital, and enterprises. In 2019, its GDP according to purchasing power parity was EUR 4.2 trillion.

Official relations between Mongolia and the Eurasian Economic Union began in 2015 with the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding. The parties established a joint working group, which successfully held the first meeting in November 2015 in Ulaanbaatar and the second meeting in November 2016 in Moscow. The consequent meeting took place in Ulaanbaatar in 2017 as part of a business forum. As a result, the Mongolian side officially expressed its interest in concluding a free trade agreement with the EAEU.

The first consultative meeting on the establishment of a joint working group to study the possibility of concluding FTA between Mongolia and the Eurasian Economic Union was successfully held in May 2020.

The lowering of tariff and non-tariff barriers with the EAEU as part of a free trade agreement is seen by the Mongolian side as an important vehicle to diversify its geographic trade structure and to reduce its dependence on China.

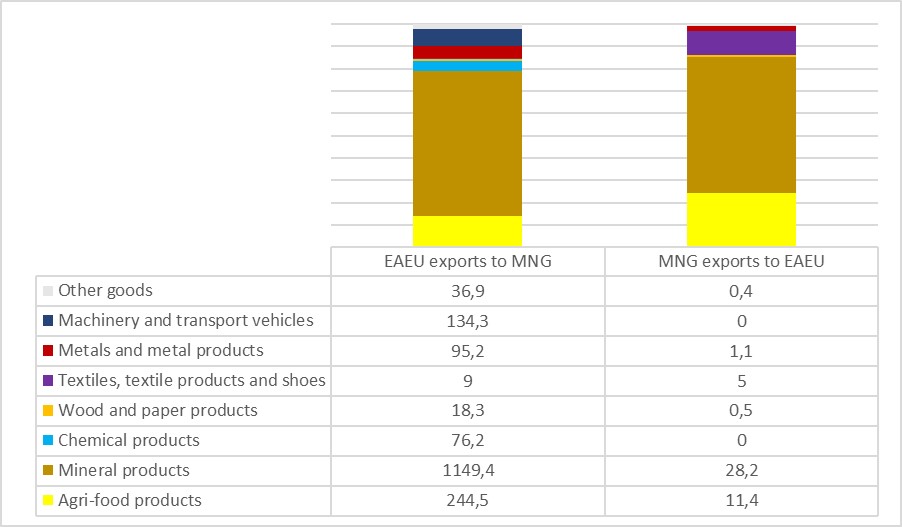

Using Comtrade data, in 2018 Mongolia exported to the EAEU member states mainly mineral products (60.5 percent), agri-food products (24.5 percent), mainly animal products, and textile products (10.7 percent). The EAEU’s export structure to Mongolia was somewhat more diversified, with minerals taking up 65.5 percent – mostly petroleum, agri-food products 13.9 percent, metals 5.4 percent, but also machinery and transport vehicles 7.6 percent (Fig 1.).

Fig. 1. Mutual MNG-EAEU goods trade structure (2018, in USD mln)

Source: Author’s calculations using the WITS database (UN Comtrade).

Simulation methodology and counterfactual

Using a multi-sector partial equilibrium model, the authors estimated the likely trade and welfare effects of a potential comprehensive free trade agreement between Mongolia and the EAEU.

As part of the comprehensive FTA counterfactual scenario tariff duties between Mongolia and the Eurasian Economic Union were set to zero. Since such free trade agreements include chapters on the approximation of technical barriers to trade, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, on customs cooperation and other aspects of trade facilitation, the authors also added a 20 percent mutual reduction in non-tariff barriers (measured in ad valorem equivalents, AVE of NTM).

The authors used the following input data for the simulation:

- Bilateral trade data from 2018 for four parties (EAEU, Mongolia, Indonesia and the “rest of the world”) aggregated for 24 MTN product sectors from the WITS (UN COMTRADE)database. For the bilateral trade flows CIF recorded imports were preferred.

- Aggregated simple most favored nation (MFN) ad-valorem import tariffs from 2018 were taken from the (WTO 2019) database. Import tariffs within the EAEU were taken as zero.

- The AVEs of NTMs for intra- and extra-EAEU trade were taken from (Knobel et al. 2019). Due to the lack of AVE of NTM estimates for Mongolia, the authors instead had to use AVE of NTMs from Kazakhstan from (Kee et al. 2009) and (Niu 2018). According to a recent paper by (Bayaraa et. al. 2019) the economic structures of Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan are the most similar to that of Mongolia. However, for the same reason, Nursultan and Bishkek might oppose trade liberalization with Ulaanbaatar, since how their trading structure is competitive rather than complementary. The AVEs of NTMs for Indonesia were taken from (Ing and Cadot 2017), as well as (Niu 2018); for the rest of the world from (Niu et al. 2018).

- Import elasticities were taken from (Ghodsi et al. 2016). The export supply (1.5) and substitution (5) elasticities were taken as constants across all sectors and regions.

Results

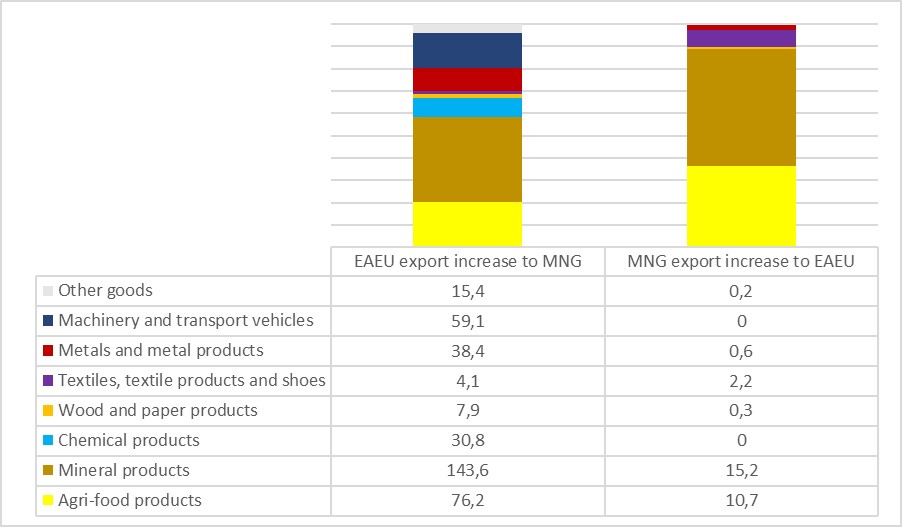

According to the simulation, a comprehensive free trade agreement between Mongolia and the EAEU, which would include the mutual removal of customs tariffs and reduction of non-tariff barriers by 20 percent, would increase Mongolian exports to the EAEU by 62.3 percent or USD 29 mln. Eurasian exports to Mongolia would increase by 21.2 percent or USD 375.6 mln. Intra-EAEU trade would decrease by USD 57.3 mln, which would equal, however, a reduction of 0.1 percent of intra-union trade. The total Mongolia-EAEU trade turnover would increase by USD 404.6 mln.

As a result, the welfare effects of such a comprehensive free trade area would be very asymmetric. The resulting increase of the EAEU’s gross domestic product as a whole would be very marginal: only 0.003 percent or USD 55.2 mln. The increase of Mongolia’s GDP, however, would be significant: by 1.9 percent or by USD 250.9 mln.

The welfare effect in the case of the EAEU is mainly due to a producer surplus of USD 60.8 million, while in the case of Mongolia it is mainly due to a consumer surplus of USD 246.3 million. In other words, the free trade area between the two parties is mainly beneficial to Eurasian producers thanks to increased exports, on the one hand, and to Mongolian consumers thanks to lower prices, on the other.

However, it is noteworthy that, as the simulation shows, there is no producer loss in any of Mongolia’s industries. Depending on the sector, the effect is either absent or positive. As a result, the aggregate producer surplus in the Mongolian economy amounts to USD 4.6 million.

In absolute figures, Mongolia’s export supplies to the EAEU member states will increase only mainly in three commodity groups: minerals – by USD 15.1 million, animals and parts thereof – by USD 10.2 million, as well as textiles and clothing – by USD 2.1 million.

The increased exports from the Eurasian Economic Union to Mongolia would be much more diversified. Petroleum exports would increase the most – by USD 112,6 mln, followed by metals (by USD 38.4 mln), minerals and precious stones (by USD 31 mln), chemicals (by USD 30,8 mln), transport equipment (by USD 26,4 mln), non-electric machinery (by USD 19,2 mln), food preparations (by USD 18,6 mln), manufactured articles (by USD 15,4 mln), electric machinery (by USD 13,6 mln), tobacco (by USD 13,4 mln), grains (by USD 10,4 mln) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Change in mutual MNG-EAEU exports due to a comprehensive FTA (in USD mln)

Source: Author’s calculations using the WITS database (UN Comtrade).