_ Michail Batikas, assistant professor, Rennes School of Business; Stefan Bechtold, Professor, ETH Zürich; Tobias, Professor, Ludwig Maximilians University Munich; Christian Peukert, associate professor, University Lausanne (HEC). Zurich, 19. October 2020. Translation into English by Yuri Kofner.

Regulations introduced in the EU for the protection of privacy and personal data have led to adaptive reactions by web technology companies worldwide – and further increased concentration in this market.

In our daily life, many geographical borders have become meaningless due to the Internet. Correspondingly, the regulatory issues in connection with digital goods and services also have a global dimension and data protection concerns do not stop at geographical borders. This raises questions about the competence of regional legislators.

As international coordination mechanisms have often proven ineffective, individual countries and regions have recently introduced rules that can have effects outside their jurisdiction. For example, some observers say that through a combination of market mechanisms and unilateral regulatory globalization, the European Union (EU) has de facto exported several of its strict guidelines, which is referred to in the literature as the “Brussels Effect” (Bradford, 2012).

In a current article, we take a closer look at the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the EU in this context. We are interested in two questions: How have websites inside and outside the EU adapted to the stricter data protection regulations of the GDPR? Has the GDPR, where the protection of privacy and personal data is concerned, led to side effects in other regulatory areas such as competition policy or industrial and trade policy?

We answer these questions as part of an empirical study of 110,706 websites over 18 months, both before and after the introduction of the GDPR in May 2018. About 20% of the websites examined have their target group in EU countries. In our data set, we can monitor the number of interactions between websites and third-party companies using HTTP requests and also assign these requests to companies in the field of online advertising technology, tracking, content delivery, etc. We also know how many cookies a website sends from third-party companies (third-party cookies), and how many cookies the website sends in its own name (first-party cookies).

On the background of the GDPR

The GDPR, the cornerstone of European data protection law, came into force in May 2018 and is considered the most comprehensive, leading data protection regime worldwide. It defines common rules for data processing throughout the EU and is binding for companies and residents in the EU, whereby consumers, companies, and countries outside the EU are also affected by a large number of mechanisms. In the context of our research contribution, the GDPR affects websites and web technology companies that are either based within the EU or offer their products and services to consumers in the EU.

The GDPR has implications for EU and non-EU websites

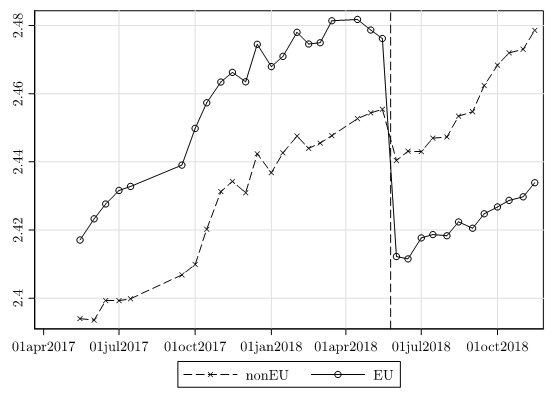

We can show that the number of third-party domains that websites interact with decreased significantly immediately after the GDPR came into force (Figure 1A). This applies not only to websites aimed at an EU audience but also to international websites. Our statistical estimate shows that the decrease is -8.1% (EU) and -2.4% (non-EU). However, this decline is short-lived (Figure 1B). According to our model predictions, websites with non-EU audiences are back to their previous level just four months after the GDPR. Websites with an EU audience return to their original level after 22 months.

Figure 1: Number of third-party companies (domains)

Note: The figure shows the logarithmized average number of third-party domains to which website hosts with (non) country-specific EU top-level domains send requests. The vertical line shows the implementation of the GDPR on May 25, 2018.

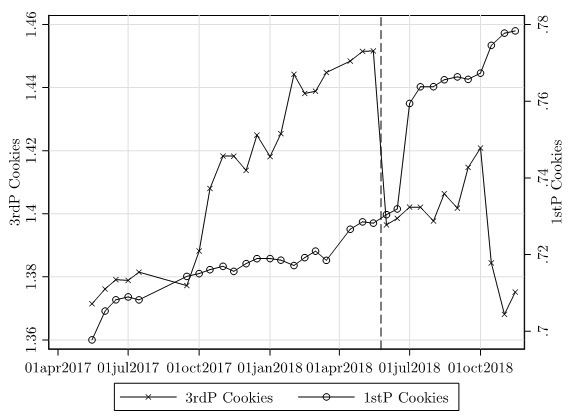

Many of the HTTP requests contain cookies, which often contain personal data. A distinction can be made here between first-party cookies and third-party cookies. The former is usually used to optimize and personalize the website, the latter is often used to sell personal data to other websites and/or companies that use personal data for their business model. We are seeing a sharp decline in third-party cookies immediately after the GDPR came into force (Figure 2a). The opposite applies to first-party cookies, in which no information is usually exchanged with others. According to our estimates, the number of third-party companies sending cookies will decrease by 12.8% (EU) and 5.5% (non-EU). At the same time, we see an increase in the number of first-party cookies for EU websites by 1.7% and for non-EU websites by 2.5%. The percentage decrease in third-party cookies is about 2-7 times as high (or 4-15 times as high in absolute terms) as the increase in first-party cookies. These changes are sustained at least in our observation period (Figure 2b / c).

Figure 2: Third-party and first-party cookies

Note: The figure shows the average number of third-party domains that respond with a cookie and the number of first-party cookies. The vertical line shows the implementation of the GDPR on May 25, 2018.

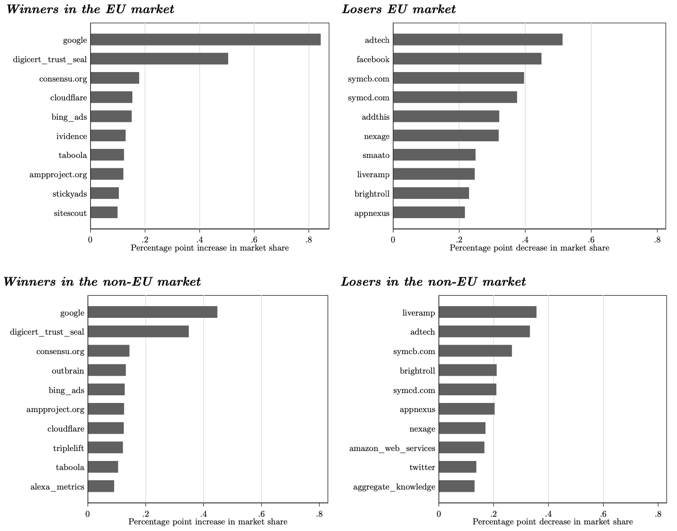

The technology market has become even more concentrated since the GDPR

The reactions of the websites have an impact on the market structure of the technology companies. We are seeing strong signs that the web technology market has become even more concentrated post GDPR. Google stands out as the clear winner, both for EU and non-EU websites (Figure 3). Otherwise, only companies that offer services for compliance with the GDPR can gain market share. The market shares of all other companies remain statistically unchanged or decrease significantly. Google is able to gain the most significant market shares in the area of analytics (7.2%) and advertising networks (5.4%), i.e. in two markets in which they had market shares of 25.8% and 38.4% respectively before the GDPR strongest were represented.

Figure 3: Top 10 companies with the greatest change in market share

Note: The time span is 6 months before and after the introduction of the GDPR on May 25, 2018. Market shares defined as the number of website hosts with (non-) EU country-specific top-level domains (EU TLDs) that Sending requests to one of a company’s domains divided by the total number of website hosts with (non-) EU TLDs sending requests to third-party companies.

Dynamic compliance risk as an explanatory approach

The GDPR has led to considerable legal uncertainty. In connection with a wider territorial application, joint liability between controllers (websites) and order processing technology companies, a drastic increase in possible sanctions, and a more effective organization of the European data protection authorities, this uncertainty leads to a drastic increase in the risk of compliance.

One way to reduce the compliance risk is to reduce the use of (non-EU) web technology companies and to switch from third-party cookies to your own cookies. Additionally, it may make sense for large web technology companies to prefer small companies because they have more resources to deal with the legal challenges created by the GDPR. Complying with the GDPR is also costly and there can be economies of scale (Gal and Aviv 2019). The GDPR has also introduced a consent requirement, which benefits large technology companies such as Google, which offer a broader range of services and can respond to regulatory requirements more quickly and effectively (Campbell, Goldfarb, Tucker 2015). Hence, the increasing focus on web technology markets could have been an unintended but inevitable consequence of the GDPR.

One way to reduce the compliance risk is to reduce the use of (non-EU) web technology companies and to switch from third-party cookies to your own cookies. Additionally, it may make sense to prefer large web technology companies over small companies because they have more resources to deal with the legal challenges created by the GDPR. Complying with the GDPR is also costly and there can be economies of scale (Gal and Aviv 2019). The GDPR has also introduced a consent requirement, which benefits large technology companies such as Google, which offer a broader range of services and can respond to regulatory requirements more quickly and effectively (Campbell, Goldfarb, Tucker 2015). Hence, the increasing concentration of the web technology markets could have been an unintended but inevitable consequence of the GDPR.

Empirical evidence for the transfer effects of data protection regulation on competition and trade policy

In the digital era, it seems to be more and more difficult to understand antitrust law and data protection law as separate legal areas with different goals, legal remedies, and enforcement mechanisms. On the one hand, network effects, a lack of competition in terms of business conditions and data protection guidelines as well as the limited effectiveness of user consent in data protection law (Acquisti and Grossklags 2005) can lead to companies strengthening their dominant market position through generous interpretation or even by violating data protection laws. As we show, laws aimed at increased privacy protection can at the same time reduce competition in related technology markets. In a world where personal data processing, user profile analysis, and consumer behavior prediction are cornerstones of highly concentrated internet markets, it, therefore, seems almost impossible to design data protection laws that have no direct impact on competition policy (and vice versa).

In our article, we document that even websites aimed at a non-EU audience employ less web technology from third parties under the GDPR and that websites are more likely to use web technology companies in the EU. This is in line with the broad territorial scope of the GDPR. According to the general principles of international public law, the EU cannot de jure regulate the processing of personal data that takes place outside the EU and is not related to the EU. However, the EU has de facto extended the reach of European data protection laws well beyond the EU’s geographical borders. First, the GDPR has wide territorial applicability, affecting websites and web technology companies regardless of their location, as long as they offer products and services to EU residents. Second, in order to save costs, some global tech companies have chosen to apply the GDPR to all of their customers worldwide, although the GDPR does not oblige them to do so. Accordingly, the quasi-export of regulation can influence trade opportunities and ultimately trade flows, especially when regulation is based on a large economic area like the EU.

Literature

A. Acquisti, J. Grossklags, Privacy and Rationality in Individual Decision Making. IEEE Security & Privacy. 3, 26–33 (2005).

A. Bradford, The Brussels Effect. Northwestern University Law Review. 107, 1–68 (2012).

J. Campbell, A. Goldfarb, C. Tucker, Privacy Regulation and Market Structure. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy. 24, 47–73 (2015).

M. S. Gal, O. Aviv, The Competitive Effects of the GDPR. Working Paper (2019).

Source: https://www.oekonomenstimme.org/