_ David Vine, Professor of Anthropology, American University; et al. Washington D.C., 21 September 2020. Republished from the original paper with some chapters and the literature list omitted.

Vind D. et al (2020). Creating Refugees: Displacement Caused by the United States’ Post-9/11 Wars. American University.

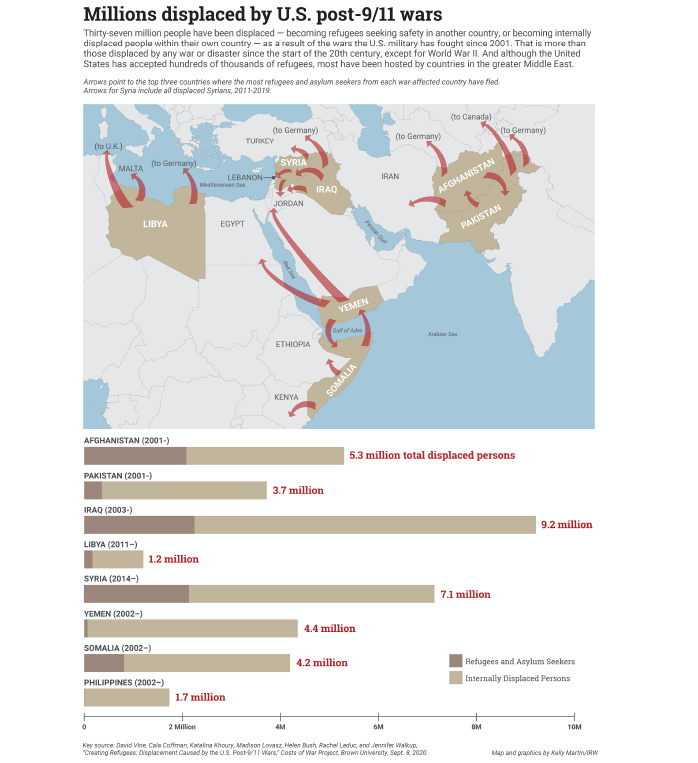

Since President George W. Bush announced a “global war on terror” following Al Qaeda’s September 11, 2001 attacks on the United States, the U.S. military has engaged in combat around the world. As in past conflicts, the United States’ post-9/11 wars have resulted in mass population displacements. This report is the first to measure comprehensively how many people these wars have displaced. Using the best available international data, this report conservatively estimates that at least 37 million people have fled their homes in the eight most violent wars the U.S. military has launched or participated in since 2001. The report details a methodology for calculating wartime displacement provides an overview of displacement in each war-affected country and points to displacement’s individual and societal impacts.

Wartime displacement (alongside war deaths and injuries) must be central to any analysis of the post-9/11 wars and their short- and long-term consequences. Displacement also must be central to any possible consideration of the future use of military force by the United States or others. Ultimately, displacing 37 million—and perhaps as many as 59 million—raises the question of who bears responsibility for repairing the damage inflicted

on those displaced.

- The U.S. post-9/11 wars have forcibly displaced at least 37 million people in and from Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, the Philippines, Libya, and Syria. This exceeds those displaced by every war since 1900, except World War II.

- Millions more have been displaced by other post-9/11 conflicts involving U.S. troops in smaller combat operations, including in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, Niger, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia.

- 37 million is a very conservative estimate. The total displaced by the U.S. post-9/11 wars could be closer to 48–59 million.

- 25.3 million people have returned after being displaced, although return does not erase the trauma of displacement or mean that those displaced have returned to their original homes or to a secure life.

- Any number is limited in what it can convey about displacement’s damage. The people behind the numbers can be difficult to see, and numbers cannot communicate how it might feel to lose one’s home, belongings, community, and much more. Displacement has caused incalculable harm to individuals, families, towns, cities, regions, and entire countries physically, socially, emotionally, and economically.

Methods and Approach

The statistics that provide the basis for our calculations are, we believe, the best available. Statistics for refugees and asylum seekers primarily come from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which has compiled data on forced displacement worldwide since 1951. Statistics for people displaced within their countries—IDPs—comes from the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), UNHCR, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), and the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). We sought out and used multiple data sources where possible to compare and check figures.

As with our definitions (above), we follow the standards by which these leading international organizations determine who qualifies as a person displaced by war. Like these organizations and other international displacement experts, we do not suggest that war is the singular cause of displacement for those categorized as displaced by war.

Instead, we follow UNHCR, IDMC, and others in focusing on cases in which the violence of war bears primary responsibility for, or is the precipitating incident behind, people’s flight from their home.

Documenting war-induced displacement raises numerous other methodological challenges. Foremost among them is the reliability of displacement statistics. This is a perennial problem reflecting the scale of displacement; the difficulty of data collection in war zones, refugee camps, and other contexts where refugees frequently live clandestine lives; and the fact that data about the displaced frequently has political, economic, and diplomatic consequences. Unfortunately, international organizations and displacement scholars have reached no consensus about whether displacement statistics tend to underestimate or overestimate the number displaced. We discuss these and other problems in detail in the Appendix. Given these challenges, we always erred on the conservative side in our estimates. We also want to avoid any perception that we have exaggerated the scale of displacement.

Displacement linked to U.S. military activity in Syria is particularly challenging to quantify. Throughout the country’s civil war, more than half of Syria’s pre-war population has been displaced, totaling some 13.3 million people in 2018. We considered including most or all of this displacement in our calculation given the important role the U.S. war in Iraq and its birthing of the Islamic State have played in shaping the Syrian civil war. We opted instead for a more conservative approach given that U.S. involvement in the war has been relatively limited compared to that of the Syrian government, rebel forces, foreign militants, and Russian, Turkish, and other foreign militaries. While the U.S. government has provided funding, training, and other support for some rebel groups, U.S. forces only started fighting in Syria in 2014 with the start of the U.S. war against the so-called Islamic State. As a result, we focused our calculations on people displaced from five Syrian provinces where U.S. forces have fought and operated since 2014. A less conservative and arguably more accurate approach would include the displaced from all of Syria’s provinces since 2014 or as early as 2013 when the U.S. government began backing Syrian rebel groups.

Our total displacement calculation does not include millions more who have been displaced in other post–2001 conflicts in which the U.S. government has been involved as part of the “war on terror.” We have not included these displaced peoples because U.S. military involvement in other conflicts has been significantly narrower in scope, duration, and degree of combat involvement. The displacement is, however, no less significant for those affected and deserves additional investigation. We provide a brief overview of displacement in these other conflicts in the section, below, that discusses our overall calculation (“Displacement in the U.S. Post-9/11 Wars: 37 million”). First, we review the history and contours of displacement in the eight countries that are the focus of this paper.

Displacement in the U.S. Post-9/11 Wars: 37 million

Based on the methodology discussed in detail in the Appendix, we now present our total displacement calculations. As we explain in the Appendix, we were conservative in our calculations given the imprecision of even the best international displacement statistics.

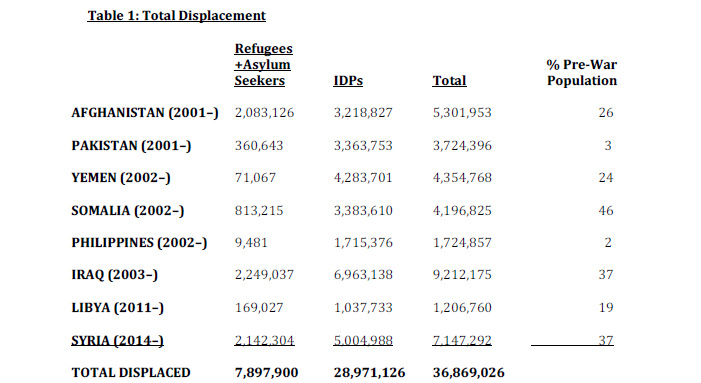

In total, we estimate that the eight U.S. post-9/11 wars that are the focus of this study have displaced 36,869,026 people (see Table 1, below). We round this total to 37 million given that our calculation is an estimate, not a precise count. This total includes refugees, asylum seekers, and IDPs numbering:

- 5.3 million Afghans (representing 26% of the pre-war population)

- 3.7 million Pakistanis (3% of the pre-war population)

- 4.4 million Yemenis (24% of the pre-war population)

- 4.2 million Somalis (46% of the pre-war population)

- 1.7 million Filipinos (2% of the pre-war population)

- 9.2 million Iraqis (37% of the pre-war population)

- 1.2 million Libyans (19% of the pre-war population)

- 7.1 million Syrians (37% of the pre-war population)

We are particularly conservative in our estimate of displacement linked to U.S. military involvement in the Syrian civil war. The 7.1 million Syrians displaced represent only those who have fled their homes in the five Syrian provinces where U.S. forces have almost exclusively fought and operated since the beginning of the U.S. war against the Islamic State in Syria in 2014. The five are Aleppo, Al-Hasakeh, Ar-Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor, and Homs. Our calculation thus excludes people displaced from other parts of Syria.

A less conservative approach would include the displaced from all of Syria’s provinces since the beginning of direct U.S. military operations in 2014 or as early as 2013 when the U.S. government began backing Syrian rebel groups. This could take the total to between 44 million and 51 million, comparable to the scale of displacement in World War II. (Some would argue that we should include all displaced Syrians given the role the U.S. war in Iraq played in shaping the Syrian civil war and the creation of the Islamic State. Adding all of Syria’s displaced likely would take the total to around 54 million.)

Given our conservative calculation methodology, we suspect that our refugee calculation in particular may be a significant underestimate. Research has shown that in 2015 there were almost as many unregistered Afghan refugees in Pakistan (1.3 million) as there were registered refugees (1.5 million). International statistics generally only count registered refugees, meaning that most of the 1.3 million unregistered Afghans in Pakistan are not included in our calculation. For understandable reasons displaced populations often avoid registering with UNHCR and other international organizations and national governments. For this and other reasons, we believe the true number of refugees and asylum seekers could be 1.5 to 2 times higher than the 7.9 million estimate found in the second column of Table 1. This could add approximately 4 million to 8 million additional displaced people to our initial 37 million estimate, yielding a total of 41 million and 45 million people displaced. With our expanded estimates for displacement in Syria, total displacement could rise to between 48 million and 59 million.

Our 37 million estimate is also conservative because it does not include anyone displaced during other conflicts in the “war on terror” where U.S. forces have been involved in relatively limited but still significant ways in countries including Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia (related to the war in Yemen), South Sudan, Tunisia, and Uganda. In most of these countries, the U.S. military (often with allied European forces) has backed national governments’ counterinsurgency campaigns and “counter-terrorism” operations against Islamist militants and other insurgents with the deployment of combat troops, drone strikes and surveillance, military training, arms sales, and other pro-government aid. In many of these conflicts, U.S.-backed governments’ “counterterror” campaigns have resulted in human rights abuses of their own civilians.

Recently, in West Africa, violence committed by local government forces and militants has displaced up to hundreds of thousands of people in a single year. In Burkina Faso, for example, there were more than half a million incidents of displacement in 2019; by year’s end, around 560,000 Burkinabe were living as IDPs. In Mali, 208,000 were living as IDPs by the end of 2019 as a result of years of violent conflict.

We note this additional displacement not to suggest U.S. culpability but to call attention to the displacement of millions of more people in other countries where U.S. forces have operated as part of the “war on terror.” More research is needed to assess the relationship between displacement and U.S. participation in these and other post-9/11 wars beyond the eight conflicts in our study.

Source: https://watson.brown.edu/

3 comments