_ Matias Cortes, associate professor, York University’s Business School, Jeanne Tschopps, assistant professor, University of Bern. ETH Zurich, 28 October 2020. Translation into English by Yuri Kofner.

If the concentration within an economic sector increases, the wage differences between companies also increase. This post shows that this is due to increasing market shares and wages of the most productive companies, arguing that increased competitive pressures can explain these patterns.

In the past few years, two important economic phenomena have received a great deal of attention from academics and policy makers. On the one hand, wage inequality has increased in many countries since the 1980s (Juhn et al. 1993; Katz and Autor 1999; Acemoglu and Autor 2011). In large part, this is due to the increasing wage differentials between companies (Card et al. 2013; Song et al. 2018; Barth et al. 2016). On the other hand, production has become increasingly concentrated, with a smaller number of companies becoming increasingly dominant in many industries (De Loecker et al. 2020; Autor et al. 2017, 2020; Grullon et al. 2019; Kehrig and Vincent 2018; Azar et al. 2020, 2018; Benmelech et al. 2018; Bajgar et al. 2019). Are these two phenomena related?

So far, the increases in wage inequality and market concentration have surprisingly been viewed in isolation. Our analysis (Cortes and Tschopp 2020) provides evidence for the relationship between these two phenomena, both theoretically and empirically, and highlights the importance of considering common drivers that may be responsible for these two patterns.

A common cause of increasing market concentration and wage inequality?

A recent study by Autor et al. (2020) argues that consumers have become more price-sensitive in recent decades, which is most likely due to increased competition in product markets (e.g. due to globalization) and the availability of new web technologies that facilitate price comparisons. We show that such a development not only increases the concentration of sales and employment in the most productive companies within the industries but also leads to an increase in the wage differentials between companies. Intuitively, increased price sensitivity shifts consumer demand to more productive companies that are able to produce and sell goods at more competitive prices. This increased demand leads to an increase in the market share and profits of these companies compared to less productive companies, while also leading to a relative increase in the wages they pay their workers. An increase in competitive pressure increases both market concentration and wage inequality between companies.

Prima facie evidence

We provide evidence for the relationship between market concentration and inequality with the help of data from the Competitiveness Research Network (CompNet), which contains information on industry level for 14 European countries for the period 1999-2016.

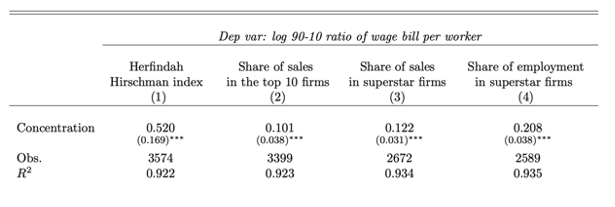

Table 1 shows the correlation between industry concentration and industry-specific wage inequality between companies using a number of different measures of concentration, namely the Herfindahl-Hirschman index of market concentration, the share of sales (revenue) in the top ten companies in an industry, and the share of revenue and employment in “superstar” companies, ie companies in the top productivity decile within their sector-country-year cell. Wage inequality is calculated as the log 90-10 ratio of labor costs per employee between firms in each industrial-country annual cell. In order to control time-changing disruptive factors at the branch or annual level, we control fixed effects at the branch and country annual level.

Table 1: Correlations between market concentrations and wage inequality

Note: The observations relate to the country – industry – year level. All regressions are weighted based on the time-averaged share of the individual sectors in the total value added in each country and include fixed values at the country and sector-year level. Superstar firms are those that are in the top decile of the TFP distribution within their industry-country-year cell.

The table shows that these conditional correlations between concentration and inequality are consistently positive and statistically significant. The estimate in column (1) implies that an increase in concentration by one standard deviation would be accompanied by an increase in inequality of about 0.05, which is slightly less than 10% of a standard deviation in the sample.

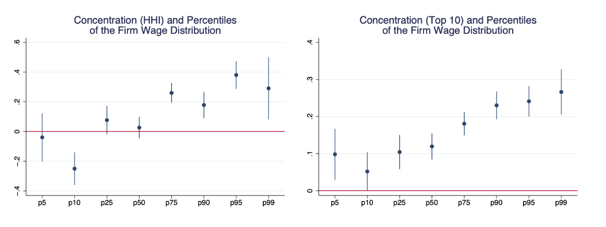

Figure 1 provides further details on the relationship between market concentration and inequality, it shows the correlations along the entire distribution of wages at the company level. We find that wages at the lower end of the distribution in more concentrated industries are either lower or only slightly higher than in less concentrated ones, while wages at the higher end of the distribution are much higher in more concentrated industries, with coefficients of 0.2 to 0.4 above the 90th percentile.

Figure 1: Results along the wage distribution at company level

Note: The figure shows the estimated coefficients and 95% confidence intervals that were determined from regressions of wages at various percentiles of the wage distribution of the companies within an industrial-country-year cell via the concentration in this cell, with fixed effects for industrial years and country years are controlled. The regressions are weighted based on the time-averaged share of each industry in the total value added in each country.

An analysis at the country level confirms that the results are widespread in European countries and do not seem to relate to country-specific circumstances. The relationship is also positive and statistically significant in most economic sectors.

Changes along the productivity distribution

Our theoretical framework is characterized by an increase in market concentration, which is due to the increasing dominance of the most productive companies within an industry. In practice, however, the increase in concentration could be linked to the fact that relatively less productive companies prevail and exploit their market power.

The data suggest that this is not the case in Europe: Our evaluations show that the increase in the overall concentration of sales is actually being driven by the increasing dominance of the most productive companies within the industries.

In our study we also find that increases in concentration are associated with almost monotonous changes in sales, wages and employment along the TFP distribution, with companies with low productivity recording a decrease in their average sales volume, wage and employment decreases and companies with higher productivity growth.

Final remarks

In summary, our results suggest a positive and statistically significant association between market concentration and wage inequality between companies in different sectors in Europe, due to the increase in market shares and wages in high productivity companies in more concentrated industries. This implies that market concentration and wage inequality between firms are linked and are likely to be driven by common factors. It is important that our results support the finding that the increased competitive pressure has led to an increased dominance of highly productive companies in Europe. Obviously, this type of “good market concentration” is less of a concern for efficiency and welfare than if it were driven by “poor market concentration”, with unproductive firms entrenching and building barriers to entry (see Covarrubias et al. 2019). In such a case, one might expect that the increasingly dominant companies could use their market power to lower white-collar workers’ wages, leading to a (relative) lowering of wages at top companies (see Stansbury and Summers 2020) and would lead to a possible compression of the sector-specific wage distribution – a pattern that contradicts our empirical evidence for Europe.

Further research into how and why competitive pressures have changed, as well as the underlying micro-level adjustments that are taking place at the company level, would be promising approaches for future research.

Literature

Acemoglu, Daron and David Autor (2011), “Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings.” Handbook of Labor Economics, 4, 1043–1171.

Autor, David, David Dorn, Lawrence F Katz, Christina Patterson, and John Van Reenen (2017), “Concentrating on the fall of the labor share.” American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 107, 180–185.

Autor, David, David Dorn, Lawrence F. Katz, Christina Patterson, and John van Reenen (2020), “The fall of the labor share and the rise of superstar firms.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135, 645–709.

Azar, José, Ioana E. Marinescu, and Marshall I. Steinbaum (2020), “Labor market concentration.” Journal of Human Resources, Forthcoming.

Azar, José, Ioana E. Marinescu, Marshall Steinbaum, and Bledi Taska (2018), “Concentration in US labor markets: Evidence from online vacancy data.” NBER Working Paper No. 24395.

Bajgar, Matej, Giuseppe Berlingieri, Sara Calligaris, Chiara Criscuolo, and Jonathan Timmis (2019), “Industry concentration in Europe and North America.” OECD Productivity Working Papers, No. 18.

Barth, Erling, Alex Bryson, James C. Davis, and Richard Freeman (2016), “It’s where you work: Increases in the dispersion of earnings across establishments and individuals in the United States.” Journal of Labor Economics, 34, S67–S97.

Benmelech, Efraim, Nittai Bergman, and Hyunseob Kim (2018), “Strong employers and weak employees: How does employer concentration affect wages?” NBER Working Paper No. 24307.

Card, David, Jörg Heining, and Patrick Kline (2013), “Workplace heterogeneity and the rise of West German wage inequality.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128, 967–1015.

Cortes, Guido Matias and Jeanne Tschopp (2020), “Rising concentration and wage inequality.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 13557.

Covarrubias, Matias, German Gutierrez, and Thomas Philippon (2019), “From good to bad concentration? U.S. industries over the past 30 years.” In NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2019, volume 34, University of Chicago Press.

De Loecker, Jan, Jan Eeckhout, and Gabriel Unger (2020), “The rise of market power and the macroeconomic implications.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135, 561–644.

Grullon, Gustavo, Yelena Larkin, and Roni Michaely (2019), “Are US industries becoming more concentrated?” Review of Finance, 23, 697–743.

Juhn, Chinhui, Kevin M. Murphy, and Brooks Pierce (1993), “Wage inequality and the rise in returns to skill.” Journal of Political Economy, 410–442.

Katz, Lawrence F. and David Autor (1999), “Changes in the wage structure and earnings inequality.” Handbooks of Labor Economics, 3, 1463–1558.

Kehrig, Matthias and Nicolas Vincent (2018), “The micro-level anatomy of the aggregate labor share decline.” NBER Working Paper No. 25275.

Song, Jae, David J Price, Fatih Guvenen, Nicholas Bloom, and Till von Wachter (2018), “Firming up inequality.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134, 1–50.

Stansbury, Anna and Lawrence H. Summers (2020), “The declining worker power hypothesis: An explanation for the recent evolution of the American economy.” NBER Working Paper No. 27193.

Source: https://www.oekonomenstimme.org/