_ Yuri Kofner, junior economist, MIWI – Institute for Market Integration and Economic Policy. Munich, 9 August 2021.

Introduction

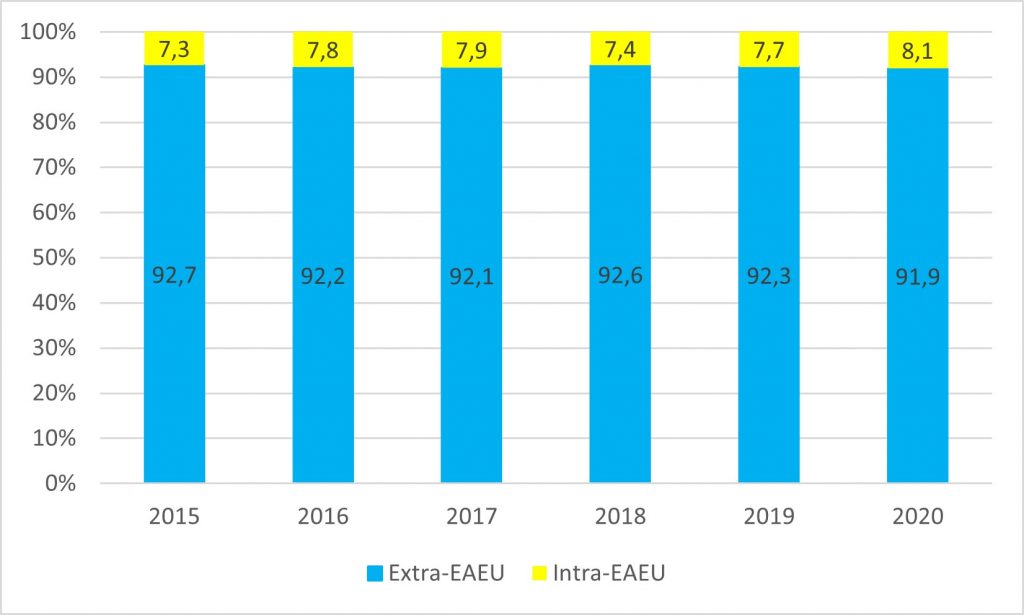

Despite significantly reducing non-tariff barriers since its inception in 2015, [1] the Eurasian Economic Union couldn’t increase intra-union goods trade in relation to extra-union goods trade, which levelled at around 7.5 to 8 percent and 92 to 92.5 percent respectively (Chart 1).

Chart 1. Intra- and extra-EAEU trade turnover (2015-2020, in percent, as share of total EAEU trade)

Source: Compiled by the author based on data by the Eurasian Economic Commission.[2]

Currently, the EAEU and its governing body, represented by the Eurasian Economic Commission, are pursuing a policy of liberalizing mutual trade in goods through the continued removal of NTBs and accompanied by the assistance of industrial corporation and import substitution.

Of course, it is necessary to continue this policy in all three aspects. Nevertheless, the author has repeatedly expressed the opinion that the EAEU should more actively jointly promote a supranational export strategy aimed at promoting its products to the markets of third parties.[3]

There are at least two arguments in favour of this logic. First, with a total population of 180 million people, the EAEU is certainly not a small market. Nevertheless, the largely overlapping structures of the member states’ economies and the relatively low purchasing power of the population limit the welfare effect(iveness) of this import substitution approach. Secondly, all successful historical examples of economic modernization, both of Western and non-Western economies, have been based on export promotion strategies.[4] The first and second arguments are based on the theory of comparative advantage in world trade.

Despite its youth, the EAEU can already show a set of preferential trade agreements with a set of third countries. There are free trade zones with Vietnam, Serbia and Iran, an agreement signed with Singapore, and there is a framework agreement on trade and economic cooperation with China.

Nevertheless, according to the author’s opinion, the EEC should revise its foreign trade doctrine in favour of an export-oriented model and intensify work on the creation of a global network of free trade areas.

A number of factors would help in the implementation of such an agenda: First, the EEC is already actively negotiating on trade and economic cooperation with a number of third parties (Tab. 1). Memorandums have been signed with some of them. Secondly, the economies of the EAEU are distinguished by not too expensive, but sufficiently highly qualified personnel, which can give a price and quality advantage for promoting their export products in developing and emerging markets. Thirdly, for political reasons, Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union have rather good and constructive relations with many of the above-mentioned markets in the so-called. “non-Western world”, for example, with Syria, CAR and Cuba. It would be worth extracting foreign economic “rent” from this accumulated geopolitical “capital”. This would also follow the idea of creating a “Greater Eurasian Partnership”.[5]

Methodology

Therefore, the aim of this study is to estimate the potential trade and welfare effects of a global free trade initiative by the Eurasian Economic Commission.

As candidates for this global free trade initiative the author chose those countries and trading blocs with which the EEC has already implented or is already actively negotiating on foreign trade cooperation and with which, according to news and expert assessments, the conclusion of agreements on an FTA has the greatest prospect of success (Tab 1.).

To do this, the author will use a gravity trade model first developed by Anderson (1979),[6] and further augmented by Santos, Silva et Tenrenyo (2006)[7] on consistency with heteroskedasticity and accounting for zero trade flows; by Fally (2015)[8] on using fixed effects to match multilateral resistances consistent with structural terms; and by Anderson, Larch et Yotov (2015)[9] on using Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimation (PPML). The latter also introduced a three-step estimation procedure with a baseline scenario, a counterfactual scenario, and a full endowment general equilibrium, – all of which will be applied in this simulation.

For the purposes of this model, the author constructed a new database, which includes data on bilateral manufactured goods trade flows for 169 countries in the year 2015, on bilateral population-weighted distance, a contiguity dummy, a common currency dummy, a dummy for being in a free trade area, and a dummy for being in a customs union based on four different datasets provided by the WTO,[10] the CEPII,[11] the United States International Trade Commission,[12] and De Sousa (2014)[13] (Formula 1):

| (1) | Xij = exp(b1lnDISTij + b2CNTGij + b3BRDRij + b4_COMCURij + b5_FTAij + b6_CUij pi + cj) + eij |

Where Xij is merchandise trade flow trade flow from exporter i to importer j; DISTij is the population-weighted distance between i and j; CNTGij is a contiguity dummy; BRDRij is a border / international trade dummy; COMCURij is a dummy if the exporter i and importer j share a common currency; FTAij is a dummy if the exporter i and importer j are part of a free trade agreement; CUij is a dummy if the exporter i and importer j are part of a customs union; pi is the exporter fixed effects; cj is the importer fixed effects; eij is the error term.

The counterfactual scenarios are implemented by setting the respective FTA dummies for the analysed countries from zero to one.

One baseline scenario (status quo of trade flows) and two counterfactual scenarios were defined: Firstly, where the Eurasian Economic Union creates a global network of free trade areas with 69 countries. This includes cooperation on a region-to-country basis, as well as on a region-to-region approach with the African Union, Mercosur, and ASEAN. The first scenario also includes those countries with which the EAEU has already implemented an FTA by 2021 (Tab 1.). The second scenario is the same as the first one, but excludes those countries, the EAEU has already implemented an FTA with by 2021. This is done to single out the trade and welfare effects of the new potentials free trade agreements, which are not in place by 2021.

Tab. 1. Global free trade initiative of the EAEU

| FTAs, implemented by 2021 |

| Vietnam (2015)

Iran (2019) Serbia (2021) Singapore (signed, implementation pending)

|

| New FTAs |

| Countries:

Azerbaijan China Ecuador Egypt India Israel Jordania Korea Mongolia Syria

Regional trade blocs: African Union ASEAN Mercosur |

Results

According to the results of the gravity model and general equilibrium procedure (Tab 2.), the creation of a global free trade network would increase gross exports of the EAEU by almost 17 percent. Armenia’s gross exports would increase by 1.8 percent, that of Belarus by 3.5 percent, of Kazakhstan by 3.7 percent, and Russian exports would increase by almost 19 percent.

As a result, this free trade initiative would increase the gross domestic product of the Eurasian Economic Union by 1.4 percent. The GDP of Armenia would increase by 1 percent, that of Belarus by 2.5 percent, of Kazakhstan by 1.6 percent and of Russia by 1.3 percent. The Kyrgyz Republic would gain the most from such a free trade initiative, which will increase its GDP by 4 percent.

If the EAEU were to realize such a global free trade network, it would make every Armenian richer by 47 USD per year, every Belarussian by 168 USD, every Kazakhstani by 184 USD, every Kyrgyz citizen by 45 USD and make every Russian citizen almost 160 USD richer yearly.

Tab. 2. Trade and welfare effects for the EAEU member states of implementing a global free trade initiative

| Implemented FTAs | New FTAs | Total effect | |||||||

| Export | GDP | GDP per capita | Export | GDP | GDP per capita | Export | GDP | GDP per capita | |

| ARM | 0.3 | 0.2 | 10 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 47 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 57 |

| BLR | 0.3 | 0.3 | 20 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 168 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 188 |

| KAZ | 0.3 | 0.1 | 12 | 6.4 | 1.6 | 184 | 6.7 | 1.7 | 196 |

| KGZ | 0.2 | 0.2 | 2 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 45 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 47 |

| RUS | 1.1 | 0.1 | 12 | 18.9 | 1.3 | 158 | 20.0 | 1.4 | 170 |

| EAEU | 1.0 | 0.1 | 16.8 | 1.4 | 17.7 | 1.5 | |||

Source: Estimates by the author. MIWI Institute.

Of course, goods trade liberalization with the Eurasian Economic Union would also have a positive economic effect on the involved third parties. For example, having an FTA with the EAEU would increase the GDP of Jordan, Tunisia, Botswana, Thailand by 0.2 percent, that of Mongolia, Azerbaijan, South Africa and China by 0.1 percent.

Eastern European countries, such as the Baltic states and Ukraine, which have opted for European integration would lose the most from not participating in the EAEU’s free trade initiative: their gross domestic product would decrease by 0.1 percent.

Using a trade gravity and multi-equilibrium model, this study shows that the adoption of an export-oriented model and the implantation of a global network of free trade areas would be the right choice, since it would significantly raise the level of well-being and economic potential of the member states of the Eurasian Economic Union.

Notes

[1] Kofner Y. (2019). Did the Eurasian Economic Union create a common domestic market for goods, services, capital and labor? URL: https://miwi-institut.de/archives/1176

[2] EEC (2021). Foreign and mutual trade in goods of the Eurasian Economic Union. URL: www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/act/integr_i_makroec/dep_stat/tradestat/time_series/Pages/default.aspx

[3] Kofner Y. (2019). Supranational Opportunities to Support EAEU Exports to the World Market. URL: http://enw-fond.ru/ekspertnoe-mnenie/9777-yuriy-kofner-nadnacionalnye-vozmozhnosti-dlya-podderzhki-eksporta-eaes-na-mirovoy-rynok.html

[4] Liberal Mission Foundation (2021). Stagnation – 2: Consequences, Risks and Alternatives for the Russian Economy. URL: https://liberal.ru/ekspertiza/zastoj-2-posledstviya-riski-i-alternativy-dlya-rossijskoj-ekonomiki

[5] Diesen G. (2019). The Geoeconomics of Russia’s Greater Eurasia Initiative. Higher School of Economics (HSE). URL: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/aspp.12497

[6] Anderson, J. E. (1979). A Theoretical Foundation for the Gravity Equation. The American Economic Review, 69(1), 106–116.

[7] Santos Silva, J. M. C. & Tenreyro, S. (2006). The log of gravity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(4), 641–658.

[8] Fally, T. (2015). Structural gravity and fixed effects. Journal of International Economics, 97, 76–85.

[9] Anderson, J. E., Larch, M. & Yotov, Y. V. (2015). Estimating General Equilibrium Trade Policy Effects: GE PPML. LeBow College of Business, Drexel University School of Economics Working Paper Series, WP 2016–06, 1–24.

[10] Monteiro, Jose-Antonio (2020), “Structural Gravity Dataset of Manufacturing Sector: 1980-2016″, World Trade Organization, Geneva.

[11] Head, K. and T. Mayer, (2014), “Gravity Equations: Toolkit, Cookbook, Workhorse.”Handbook of International Economics, Vol. 4,eds. Gopinath, Helpman, and Rogoff, Elsevier.

[12] Borchert, I., Larch, M., Shikher, S., and Yotov, Y. (2020), “The International Trade and Production Database for Estimation (ITPD-E)”, International Economics, forthcoming.; Tamara Gurevich and Peter Herman, (2018). The Dynamic Gravity Dataset: 1948-2016. USITC Working Paper 2018-02-A.

[13] De Sousa, J. (2012). The currency union effect on trade is decreasing over time. Economics Letters, 117(3), 917-920.

One comment