_ Xavier Everaert, economist, MIWI Institute, advisor on EU economic, financial, monetary and fiscal policy, Identity and Democracy parliamentary group, European Parliament. Vienna, 18 March 2022.*

Introduction

In this MIWI analytical note we will focus on six key areas of EU economic and monetary policy from a freedomly-patriotic point of view. Of course, there are more issues to discuss, but for the sake of completeness I will avoid complexity and focus on the main problems in the economic architecture of the European Union.

First, I will briefly review the economic structure of the EU, as this will form the basis for the rest of the analysis. This is important to understand the economic competences of the EU and to understand why the EU takes certain decisions instead of the member states.

Second, I will discuss the role of the euro. Why did the euro come into existence? What is the intended function? We often hear that the euro was introduced to ensure tourists don’t have to exchange their money while on holiday. Of course, the truth is a bit more complex and interesting.

Third, we will discuss the banking union and deposit insurance. This is a very hot topic and politically very important.

Fourth, we will discuss the capital markets union. This is a bit technical and doesn’t get much press coverage because it’s not as “sexy” as the banking union.

Fifth, we will discuss ongoing developments regarding the tax union. This new pillar of EU economic policy is still in its infancy but will become the centre of EU power if the commission has its way.

I will then end with something new, namely the NGEU package and the problem of the European debt.

Brief summary of the economic policy structure of the EU

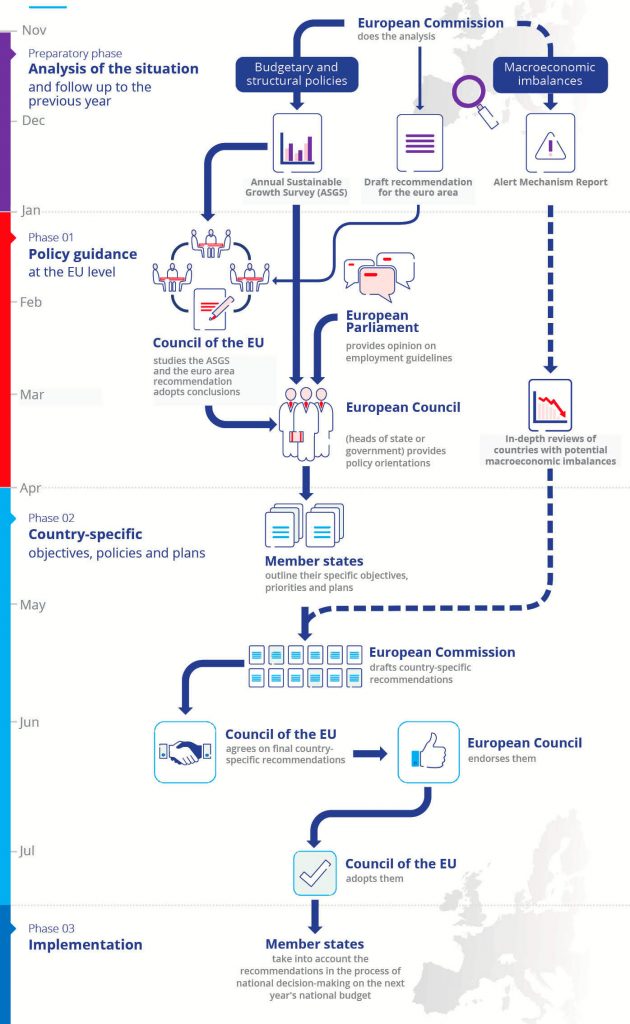

The entire economic policy of the EU comes from a single source, namely the European semester. Each member state is to report to the commission on its budgetary and fiscal policies. The commission then assesses the economic parameters of the member states and their proposed economic policies for the coming year and makes recommendations – the so-called “country-specific recommendations”. These recommendations are complemented by general recommendations of the European Parliament and endorsed by the Council of Europe.

Fig. 1. Distribution of tasks in the European semester

Source: European Council.

For Austria, for example, the recommendations for 2020 and 2021 look like this: increase investments, strengthen the resilience of the health system by strengthening public health and basic services, ensure equal access to education and more digital learning, liquidity support for SMEs, investments in the green and digital transition, sustainable transport, clean and efficient energy production, and tax reforms.

The legal value, the legal basis, of these recommendations then is being discussed. The European semester is a practice. As it is not mentioned as such in the treaties, it is theoretically not binding for the member states. And here, of course, are the problems.

What – at least in theory – can be enforced in the European semester is the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). This is an agreement between all member states to apply common rules for national budgets and deficits. This also includes a correction mechanism. It is important to note that all member states are bound by the SGP. Not only the members of the euro area.

The idea is that no member state, regardless of its economic strength, should have a budget deficit of more than 3 percent of GDP and a public debt of more than 60 percent of GDP. These requirements mirror the requirements for joining the euro area.

The reason is quite simple. The common market has made European markets interdependent. When there is speculation against an economy or an economic contraction in one member state, there are definitely consequences for other member states. This would trigger a domino effect that would be independent of economic policies in the other member states.

If countries fail to comply with the SGP, the correction mechanism should be triggered. This implies that the EU will, at least in theory, be able to dictate economic and fiscal policy within the member state in question, effectively bypassing national democracy.

The SGP has been suspended since the outbreak of the Corona crisis, probably until the end of 2023. This allows member states to take on more debt and higher deficits for the necessary investments and spending after the sanitation crisis. This, of course, has led to a massive increase in government debt.

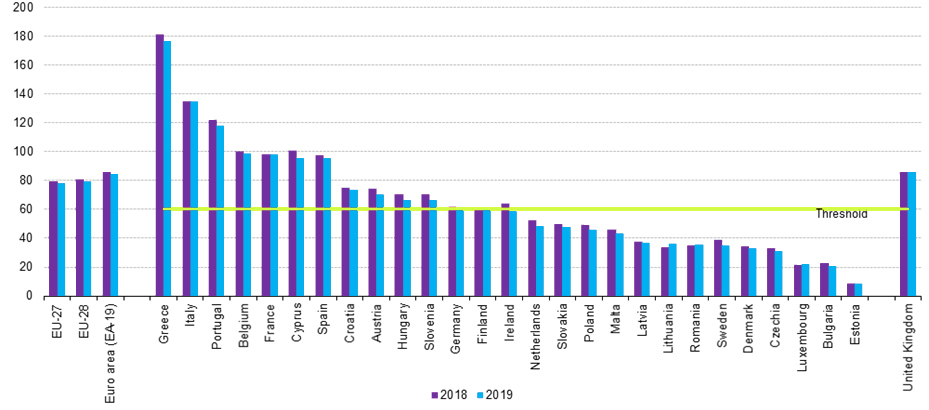

Fig. 2. General government consolidated gross debt of the EU member states (2018, 2019, as percentage of GDP)

Source: Eurostat.

If we look at government debt data for 2018 and 2019, we see that 14 out of 27 member states are in breach of SGP rules. However, the correction mechanism will not be triggered for any of these member states. One may recall the crisis in Greece and Cyprus in 2008. The “correction process” for these countries ended last year.

The reason why the corrective mechanism was not triggered: Most of these countries have budget deficits of 3 percent or less.

Nowhere in the European treaties do we read that the SGP requirements should be applied cumulatively, but this appears to be an ad hoc rule applied by the commission and the ECB.

What one may notice is the fact that western and southern member states tend to have higher national debts than northern and eastern European countries. The same applies to larger economies compared to smaller economies. Indeed, this is statistically significant.

In terms of regional differences, the former communist countries have had better growth over the past 20 years, meaning tax revenues have been high and therefore less dependent on debt financing.

As for the size of the economy, this is a matter of simple accounting: countries operating with larger balance sheets naturally have a larger passive side and can carry more debt. Please note that this is the size of the economy and not the size of the country. Countries like Greece, Cyprus and Portugal are small but have relatively large economies, largely due to their maritime power. This also means a relatively large financial sector.

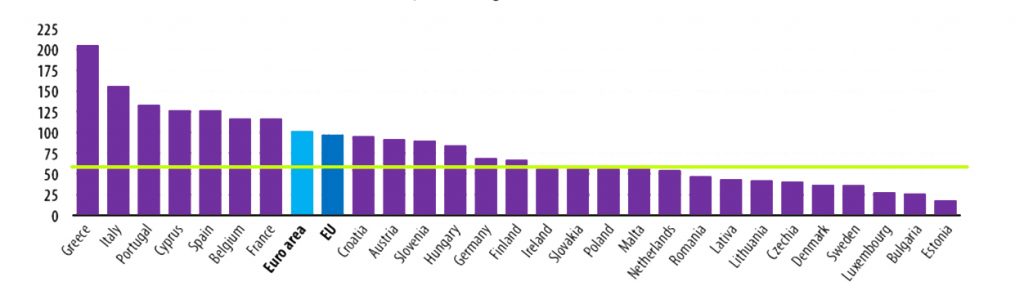

Fig. 3. General government consolidated gross debt of the EU member states (I 2021, as percentage of GDP)

Source: Eurostat.

In the first quarter of 2020, the average debt ratio in the euro area was 86.1 percent. In the first quarter of 2021 it was at 99.5 percent.

In 2019 we saw 14 out of 27 member states breaking the rules. In early 2021 it was almost twenty.

Seven member states had a debt of over 100 percent of GDP. Five of them had a public debt double or more than double what the SGP allows: Spain and Cyprus had 120 percent. Portugal 133 percent, Italy 155 percent, Greece 205.6 percent.

Spain, Greece and Cyprus had almost a 30 percent higher debt than at the start of 2020.

Austria, on the other hand, has a national debt of 87.4 percent, which is 14 percent higher than at the beginning of 2020. This corresponds to the EU average.

Taken together, this constitutes a significant problem: most member states break the SGP rules. Public and private debt are piling up. There is only one country that has never broken the rules: Luxembourg.

And there also is a major democratic deficit: with the European semester as such unenforceable, national governments are reluctant to change their economic policy objectives, as this would mean deviating from the plan, which has won them the parliamentary majority in their respective national parliaments.

And with none of the member states playing by the rules, there is now political pressure to change the rules to suit their behaviour. In February 2022, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), which deals with providing emergency fiscal support to member states in the event of financial distress, proposed the idea of raising the debt ceiling from 60 to 100 percent.

Role of the euro – necessary condition for the single market

Debt as such is not a problem as long as one can afford it. The EU has always said that the debt problem will solve itself as the euro ensures that the economy grows fast enough for any debt level to be sustainable. Let’s examine this claim.

As I argued in the introduction, we often hear that the euro made it easier for tourists to cross borders without having to exchange money. This is of course an interesting convenience, but not the reason why the single currency was introduced.

Fig. 4. Presentation of the Fiat Nuova 500 model in Turin (1957)

Source: Fiat.

In Fig. 4. one sees the Piazza San Carlo in Turin. Turin is the city of Fiat. Fiat was – until recently – the pride of the Italian economy. Fiat’s success was based on a business model that would be illegal today under both WHO and European rules: direct money financing.

Noting that VW was gaining market share, Gianni Agnelli, the CEO of Fiat, made a phone call from Turin to Rome and asked the Bank of Italy to print more money. This would mean that prices would fall, Agnelli could invest and increase production cheaper, and sell his cars cheaper across Europe. This is a privilege VW didn’t have, as the Bundesbank has always refused to drastically increase the money supply.

What the Italian economy lacked in competitiveness it could make up for in price. Of course, this strategy did not seem to be compatible with the idea of a single market in Europe.

Shortly after the conception of the single market in the 1960s, the founders of the EU realized that a single market required a single currency.

This was the reality in currency competition:

More competitive economies like Germany had strong currencies. The Deutschmark was an international reserve currency, inflation was low, and German products were competitive and of high quality. There was a demand for goods made in Germany because they were good. And people were willing to pay extra for reliable, high-quality goods.

A strong, expensive currency also means less inflation, but also more expensive capital and debt. Therefore, it is not interesting for such a state to take on debt: however, the state can count on economic growth and high wages for tax revenue.

Less competitive economies like Italy had weaker currencies. Many lira circulated in the Italian economy, it did not flow abroad, there was high inflation and its exports were based on price rather than quality.

A weak, cheap currency made life cheap for Italians, and Germans traveling to Italy, but it was also cheap for the Italian government to borrow to fund social and infrastructure projects. High inflation made saving less attractive, so the tax base fell, and the government relied more on debt financing.

How could one arrive at a compromise between two very different monetary philosophies?

In the 1980s and 1990s, Europe agreed to the introduction of a common currency that would mimic the Deutschmark. It would be a strong currency with low inflation. This meant inflation below 2 percent y.o.y.

This, of course, made production and the cost of living very expensive in weaker economies. After the introduction of the euro, the price of a coffee in Italy almost tripled.

To mitigate this negative impact, the ECB would buy corporate and government bonds from weaker countries. This could be seen as fiscal doping. It is not much different from cash financing. Instead of pumping money into the economy to lower the cost of money, the ECB buys bonds at market prices to lower the cost of financing debt. From an accounting perspective, it is the same.

The euro was a flawed system from the start.

Proponents of the euro assumed that over time the euro would become relatively cheaper than the Deutschmark for Germany. They were correct. Compared to the size of the German economy, the euro is too cheap. This means that the euro is a de facto export subsidy for German industry. Of course, this creates wealth and jobs, but it also keeps the value of wages and pensions low.

On the other hand, Italian companies were allowed to borrow at German interest rates. Where they had previously paid around 10 percent interest on a commercial loan, it had dropped to 2-4 percent. And they were right again. After the introduction of the euro, there was massive investment in the Italian economy and the country’s industry was able to modernize very quickly.

Initially, the supporters of the euro were right. The single currency created a real single market: all European companies could finance themselves under the same conditions and prices for all Europeans were more equal than ever before.

However, we found that the prices were not so the same for all Europeans. Economists use a benchmark for consumer goods, the Nutella Index. It compares the price in euros for 1 kg of Nutella across the euro area. It is similar to the Big Mac Index, which is used as an international benchmark for all currencies.

We find that Nutella was actually up to 25 percent more expensive in Italy than in Germany. Why is that? How is it that consumer goods containing the exact same ingredients are more expensive than elsewhere using the exact same currency?

We also note that the flow of capital from Italy to other member states is currently close to 550 billion euros, while proponents of the euro claimed it would be zero. If you can invest your euro anywhere at the same cost and interest rate, why take it out of one member state and invest it elsewhere? Something is wrong here.

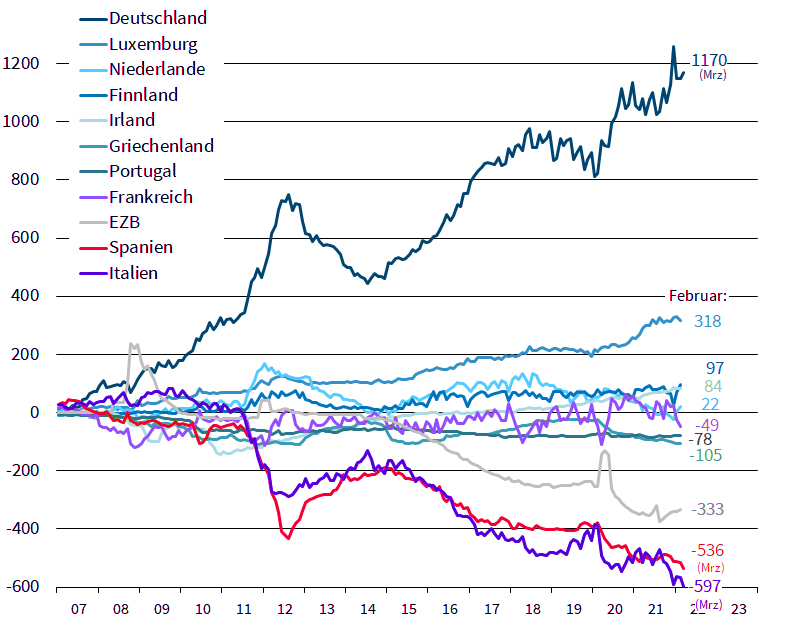

Fig. 5. Net TARGET II balances of selected national central banks and the ECB (2007-2022, in bln euros)

Source: Sinn H.W. (2022). URL: https://www.hanswernersinn.de/de/themen/TargetSalden

This is not the only problem. As one might recall, the proponents of the euro were right that the euro would be relatively cheap for Germany relative to the size of its economy.

However, we were not able to identify a significant increase in German exports. In fact, German industrial production stagnated.

Yes, it has become cheaper to invest in the Mediterranean economy, but we see capital fleeing southern Europe.

Indeed, the internal market works in the sense that it is easier for an Austrian entrepreneur to sell his goods in Spain than it was 25 years ago. However, relative to the expansion of the economy, residential real estate in Italy has become cheaper, while in certain German cities the real estate price has doubled.

In short, the euro seems to produce only losers. Of course, the economy has grown and we are much richer than 20 years ago. This cannot be denied. But we also owed a lot more and could have been a lot richer. Don’t forget that the euro has lost 30 percent of its value since its inception. People who have not increased their wealth by 30 percent over a 20-year period, such as retirees or the poor, are poorer today than they were in 2001.

It’s getting harder and harder to see who wins from the euro 20 years later.

Banking union and deposit insurance

So far, we have talked about debt and the money system and how the EU has affected them. Now we will talk about equity and savings under the banking union.

We have only looked at the economic and fiscal side of the problem: production, investment and public debt.

The banking union addresses a different problem, namely private debt. Largely the problem of bank solvency.

One may have heard of the Basel Rules. These rules tell banks how much capital they must have on their balance sheets. It works like this: Households come to the bank with your savings. They agree with the bank to receive a certain interest rate. The bank then lends entrepreneurs the households’ savings to invest. The more money invested, the more revenue for the bank, the more interest households receive on their savings. A bank with a good reputation can spend every euro entrusted to them multiple times. This means: for every euro households give them, they loan entrepreneurs about 4 euros. This is fine as long as households don’t claim their euro back. It means money is invested in the real economy, the economy grows and households get a good interest in their savings.

But we need rules in case the economy shrinks, and entrepreneurs don’t make the profits the bank hopes for. To minimize this risk, we have the Basel rules. These rules ensure that a bank holds a certain amount of capital. This is known as the capital buffer.

In the EU, the capital buffers of the largest banks are monitored by the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM). They ensure that banks do not run into solvency problems when the economy shrinks or too many loans default.

If the SSM is not doing its job very well and a bank gets into trouble, there are rules for recapitalization.

If the recapitalization does not work, the bank must be dissolved. This is another word for controlled bankruptcy. This usually means bad assets are taken off the market and good assets are sold to other banks.

When Europe’s largest banks fail, the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) is responsible.

Of course, if a bank fails, we have to somehow protect the interests of savers. In all European countries there is some kind of deposit insurance. All savers pay a contribution to a national fund that covers up to 100,000 euros in savings per saver per account in the event of a bank failure.

Because of the internal market, one can open a bank account anywhere in the EU. However, since deposit guarantee schemes are exclusively national, the likelihood that one’s savings can be guaranteed naturally depends on the reliability of the national scheme. In some countries there are doubts about the regulations. For this reason, the EU would like to monitor these systems better and combine them into a European deposit guarantee system. Luckily this is not operational yet. It seems like a good system on paper.

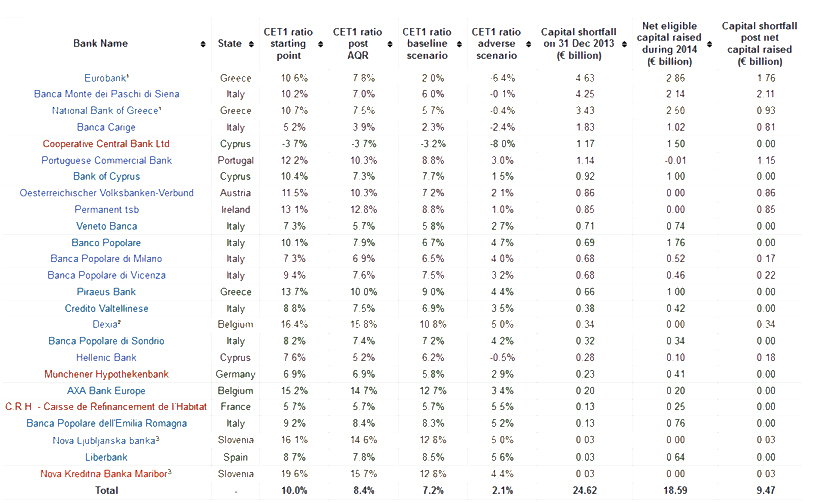

Many European banks are still reporting deficits in their capital buffers. Figure 6 is from 2013, but unfortunately it still agrees with today’s observations. This means that the supervisory structure does not seem to work very well.

Fig. 6. SSM participating banks with a CET1 capital shortfall (2013)

Source: ECB.

This has two main consequences. First, advocates of European integration demand more centralized European control. They distrust the national supervisory authorities in dealing with the smaller banks. This is bad news for national sovereignty, but objectively there is a point. A few scandals have made it very clear that some national regulators are not doing their job properly.

Second, countries with smaller banks, such as Austria and Germany, complain that the rules are being made in favour of large banks that can afford expensive compliance requirements. Of course, this also applies. Compliance costs for smaller banks are relatively higher than for larger banks.

The European supervisory authorities are not really concerned with this criticism. The have said on many occasions that these smaller banks should consolidate, i.e., merge. They prefer a European Union with fewer but bigger banks. However, this is a very sensitive issue in countries where smaller banks are an important part of the financial culture. There is also ample evidence that smaller banks were much more resilient to the 2009 financial crisis than larger banks.

Currently there are many discussions in Brussels about the European deposit insurance scheme (EDIS). This would be a kind of insurance in case of a failure of the national insurance systems.

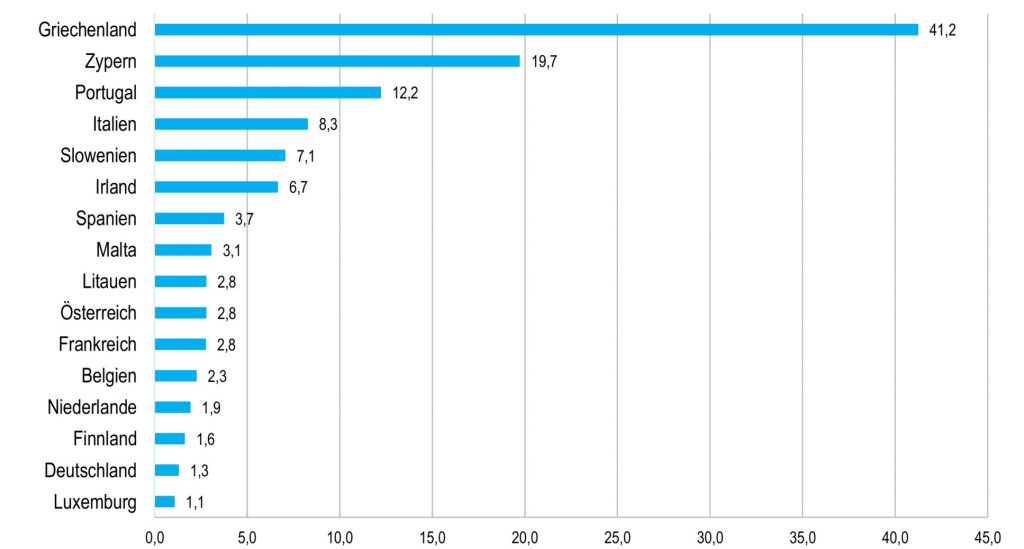

In the EU there are many non-performing loans (NPL). NPLs are outstanding loans that banks know the creditor will not be able to repay the loan. As one can see in Figure 7., in Greece the NPL is over 40 percent of all outstanding loans. Out of 10 people who have borrowed money from a Greek bank, 4 definitely cannot repay the loan. In Austria the benchmark is 2.8 percent. In Germany – only 1.3 percent.

Fig. 7. Non-performing loans in selected EU member states (2019, as share of the total loan volume)

Source: Büchel A. (2019). Genossenschaftsverband Bayern. URL: https://www.profil.bayern/09-2019/topthema/wie-eine-abwaertsspirale/

The four countries with the highest share of NPLs are Greece, Cyprus, Portugal and Italy. The usual suspects.

This means that these countries are much more likely to benefit from European deposit insurance than countries like Germany and Austria. This means that Austrian savers would have to pay fees to the European deposit insurance scheme, which is used to bail out banks in southern European countries.

So EDIS is the textbook example of a North-South redistribution mechanism.

Another problem is that EDIS ignores national banking practices. Austria has two, soon three separate deposit guarantee schemes, Germany has four. There is no political will to merge them as they operate under different business models.

Capital markets union

The capital markets union is not a very “sexy” topic since it is more technical. Nevertheless, it is very important.

Europe has a financial market that is very different from other developed countries: it is very dependent on banks and credit. In the US or in Asia, it is much easier for companies to find capital directly from investors. They don’t typically use banks as intermediaries. This type of direct financing is called the capital market.

The EU wants to reduce the traditional European dependency on banks. In itself this is not a bad idea. In the 2009 financial crisis, American and European banks were in trouble. However, this did not have a major impact on the real economy in the US as companies became less reliant on banks. In Europe it was a disaster.

Thus, the analysis is correct. However, there is another side to the story.

First, there is no European venture capital market. A capital markets union in the EU would therefore mean that we create rules that strengthen the power of American and Asian investors in European companies. I am not convinced that this mimicry will benefit the stability of the EU economy.

Second, some European economies are very weak and vulnerable to speculators. Now one could mitigate this by asking the ECB to again buy Italian bank bonds. Because banks are very important for the resilience of European economies. As our economies become less dependent on banks, the power of this weapon will diminish. And it will be very difficult to tell American and Chinese hedge funds what they can and cannot do.

There is also something called the PEPP. It is a rather technical concept, but one can think of it as a European private pension. Europeans are very dependent on state pensions. The market for private pensions is not very developed in the EU. By creating an EU legal framework, the EU is trying to create a common European market for private pensions. This has two implications.

Firstly, European pension funds from Austria could invest in real estate or infrastructure projects in Italy in search of higher returns.

Second, US pension funds could operate in European markets.

This could be of interest to consumers as they can earn higher returns on their pensions. On the other hand, we are selling our pension market to foreigners. We are also ignoring the root cause of low returns from our pension funds: the ECB’s accommodative monetary policy.

Everyone agrees that in the EU the investment rate is quite low compared to the rest of the world. However, very few people ask why that is.

Why do we have low investment rates in the European economy?

Perhaps investors have doubts about institutional safety. Can Italy go bankrupt? Can Italy leave the euro area? How will the market develop in 2050 when certain countries will have a democratic majority of Muslims? All of these are questions that make it very difficult for investors to make the right long-term investment decisions.

What about monetary risk? Will the ECB keep interest rates low or below zero for an extended period? When will interest rates rise again? What will happen next? It is therefore very difficult for investors to make investments denominated in euros.

As I said, will it be beneficial or detrimental to the stability of the European economy to make our economy more dependent on foreign investment funds and financial products?

In Brussels one notices a lot of foreign lobbying on the capital markets union files, particularly by American corporations. They are pressuring the commission to pass a regulatory framework that mimics American rules. Is that in our interest?

We have also seen a sharp increase in compliance requirements for banks and financial intermediaries. After the introduction of MIFID and MIFID II in the last decade, both multinational banks and small insurance agents have had to inform clients about their investment strategies and the use of financial products. These information requirements are intended to inform the customer about the products they are purchasing. This is easy for an investment bank with thousands of employees, but not for a small notary in a Carinthian village proposing to a client to put a legacy into a trust fund for tax purposes.

Thas, what would we actually need?

First, we need to normalize interest rates. The ECB lowered interest rates in 2009 to give banks more time to improve the health of their balance sheets. These banks have now had more than ten years, yet the ECB is still expanding its purchasing programs. Of course, why would a bank improve its balance sheet when it is rewarded for bad management with low interest rates on its loans?

If we normalize interest rates, investors can more easily see which projects in the market seeking financing are more reliable and profitable than others.

The normalization of interest rates will also lead to a “clean up” of the banking sector. Many banks will default as interest rates rise, meaning bad banks will be penalized for poor management and good banks with higher market share will be rewarded.

Something I think the EU is doing well is imposing capital buffer rules. This makes banks healthier and discourages them from making very risky investments. However, since the Corona crisis, we have seen some political pressure to lower capital buffers, also in the context of Basel III rules. This would mean that banks can invest more in order to earn higher returns. This will of course increase volatility and risk in the European banking sector.

And of course, we need more transparency and protection for consumers and shareholders.

Tax union

As one knows, the EU is financed by contributions from the member states’ tax revenues. However, we find that countries have a harder time maintaining sales levels. This is because many Europeans are finding ways to streamline their taxes. Since there is free movement of capital, it is relatively easy for European citizens and businesses to develop tax purposes in different member states. For example, it is cheaper for a Polish pedlar to register his company and van in Poland, but to pursue his professional activities in Austria.

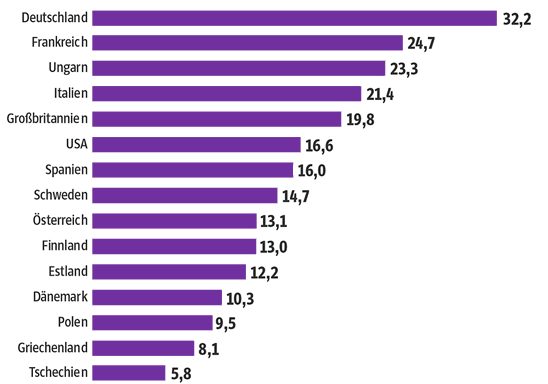

In Figure 8. one sees that Austria is missing about 20 percent of tax revenue per year as a result. 13 percent of this for tax havens. In Germany, up to a third of all tax revenue is lost.

Fig. 8. Lost tax revenue (2017, share of actual revenue)

Source: Zucman G. (2017). Motor der Ungleichheit. University Berkeley. URL: https://www.sueddeutsche.de/projekte/artikel/wirtschaft/steueroasen-befeuern-ungleichheit-e198908/

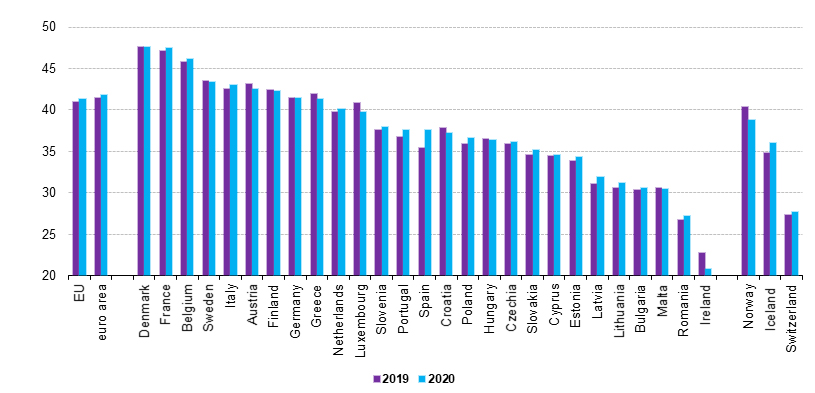

On the other hand, in Figure 9. one sees that taxes are usually very high in countries that lose a lot of tax revenue. This raises questions of causality. Do people take their money out of a country because taxes are high, or do countries increase their taxes because more money is flowing out?

Figure 9. Tax revenue by EU member states (2019, 2020, in relation to GDP)

Source: Eurostat.

What is clear, however, is that taxes are distributed very unequally throughout the EU. The tax burden in France is twice as high as the tax burden in Ireland. This is a competitive advantage for Ireland. The European Court of Justice has recently ruled that under certain circumstances, low taxes constitute illegal state aid.

To a certain extent, tax harmonization makes sense. Member states are overly dependent on debt financing. Increasing tax efficiency would therefore put less strain on governments to issue debt.

It could also be interesting to put EU-wide pressure on tax havens.

On the other hand, according to the EU treaties, taxation is an exclusive competence of the national member states. This does not mean that the EU cannot legislate on taxes. In fact, there are many policies and regulations related to taxation. But it needs unanimity in the Council (Art. 114-115 TFEU). This means that each country has to agree to the rules. That almost never happens. Countries like Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands have typically vetoed harmonization of public finances.

Fiscal harmonization also always benefits countries with high taxes. Smaller countries with fewer resources can only use fiscal policy to be competitive. This is almost the only way to attract capital and investments. If they are forced to raise their taxes, they lose their competitive advantage. This means these countries are becoming less competitive and poorer. This in turn means that a decreasing number of competitive member states must support an increasing number of uncompetitive member states.

Next Generation EU, supranational debt and the transfer union

The year is 2019. EU banking supervision is performing. EU banking rules work very well. Banks have strong capital buffers and are overall healthy, liquid and solvent. Public and private debt is high, but interest rates are low enough to keep the debt affordable.

Then comes 2020 and the Corona crisis with its lockdowns and restrictions. This leads to massive economic fallout. There have been especially many Corona cases in southern European countries and speculations against the debts of these countries arose. Many companies had no income, they could not repay their loans and had to go bankrupt. Millions of jobs were threatened. Later, inflation started to rise again.

In July 2020, five months after the first outbreak in Europe, the European Council agreed on the Next Generation EU programme. This is a 750 billion euro fund made up of grants and loans. They are not financed from own assets via the EU budget. It is a shadow budget alongside the official budget, funded by debt. This raises several problems. Under the strict interpretation of the treaties, the EU is clearly prohibited to issue debt instruments. The EU treaties are very clear on this and state that the EU budget must be financed entirely from own resources (assets). In short: via contributions from the member states, mostly via VAT and customs revenues.

However, in the past the EU already issued debt instruments for several specific and targeted programmes. These programs, like NGEU, were limited in scope and time. In fact, NGEU is supposed to drive the “greening and digitization” of the European economy, and the program only runs “until 2026”. A German initiative to stop the NGEU failed based on this justification.

Thus, 750 billion euros in the EU will be debt financed. The member states are forced to invest them in “green and digital” projects. So far, “so good”. Now the question remains: Who gets what and who pays back which part of the debt?

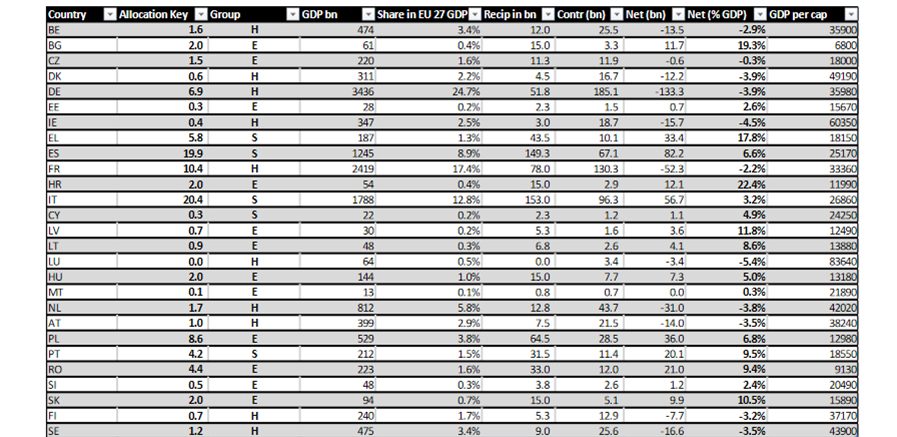

The council has drawn up a distribution key for this purpose, which is outlined in Figure 10.

Fig. 10. NGEU net allocation key (in 2019 prices, in relation to GDP and in bln euros)

Source: European Commission.

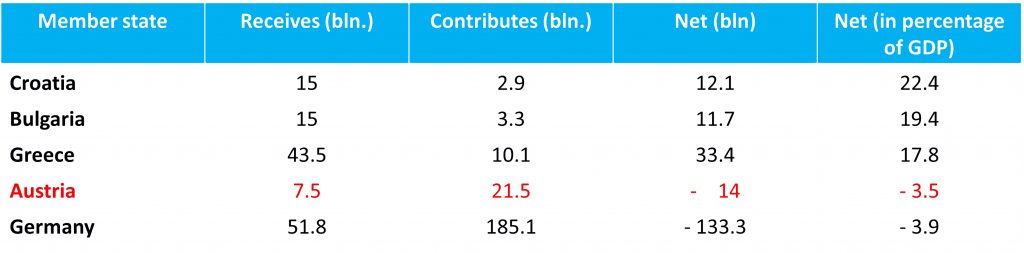

Italy and Spain each receive around 150 billion euros from the fund, meaning they split about half of the total fund between themselves. In terms of net gain as a percentage of GDP, Croatia receives the most. Over the next five years it will receive around 22.4 percent of its GDP in European subsidies and credits. Followed by Bulgaria with 19.4 percent and Greece with 17.8 percent. Incidentally, according to Transparency International, Croatia is one of the most corrupt countries in Europe. Globally, it even ranks behind Cuba.

Austria receives 7.5 billion euros from the fund. However, Austria contributes 21.5 billion euros to the NGEU budget. This means that the NGEU means a net loss of 14 billion euros for the Austrian taxpayer, about 3.5 percent of GDP. This means that on top of the economic damage Austrians suffered from the Corona restrictions, they pay another 3.5 percent of their output to countries like Croatia, Bulgaria, Greece, Romania, Italy and Spain.

As one can see, it is even more unjust for Germany, which faces a net loss of 133.3 billion euros, or almost 4 percent of its GDP (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11. NGEU net allocation key for selected EU countries (in 2019 prices, in relation to GDP and in bln euros)

Source: European Commission.

On February 12, 2021, the NGEU was officially founded. Which amounts have been paid out by early 2020?

Croatia received 1.6 percent of its GDP as pre-financing. Austria received 450 million euros, tantamount to 0.1 percent of GDP. Measured by GDP percentage one can say with certainty that for the EU one Croat citizen is worth 16 Austrians and about 26 Germans (0.06 percent of GDP).

So far, Italy has received 420 euros per inhabitant. Austria received 50 euros, Germany 27. In terms of money per capita, this means that for Brussels one Italian is worth 8.4 Austrians and 15.5 Germans.

Regardless of what one thinks about Corona, public investment and European solidarity, it is obvious that the NGEU is consolidating the European Union as a transfer union.

Role of the European Parliament in economic policy

As a legislator, the European Parliament’s role in economic affairs is quite large compared to other areas. According to Article 294 VWEU, the European Parliament is co-legislator with the Council for economic governance. This applies to everything stated above about the banking union and the capital markets union.

On other issues, the Council is the sole legislator. This means that the European Parliament is only consulted. This does not mean that its opinion does not matter, yet it only has a “diplomatic value”. If an MEP plays his role well, he can put pressure on his member state in the Council. This applies to issues of taxation and money laundering, competition policy and harmonization outside the area of internal market policy.

Although the European Parliament has a lot of power on paper in economic matters, one doesn’t much of these alleged powers in practice. MEPs from the main parliamentary groups are very keen to receive contributions from lobbyists.

The more interesting, more critical amendments to EU legislative initiatives come from the left-wing groups and from the right-wing “Identity and Democracy” group. However, these changes are rarely taken into account. Sometimes amendments by the Lega party are taken into account. Yet that is so, since the Italian Lega is fairly moderate on economic issues and sits in government. For a party like the AfD, it is highly unlikely that its amendments will be accepted.

The likelihood of a report not going through the Economics Committee is virtually zero, although the likelihood has increased since the beginning of this legislature. For example, the report on the European semester failed to win a majority for the third consecutive year. This is of course due to the good work of “Identity and Democracy” parliamentary group, which has more than doubled its size on the ECON Committee compared to the previous term.

However, it is also becoming more difficult for groups to find stable majorities, as the two main groups EPP and SD no longer have a majority.

Conclusion

Following are the main points from this MIWI analytical note:

The source of all economic and financial regulation in the European Union is the discussion about the optimal functioning of the European single market(s). This requires convergence in macroeconomic indicators and monetary policy.

Currency convergence requires a corrective mechanism to control budget deficits and government debt.

We have seen that the EU correction mechanisms are not working.

Therefore, the EU is forced to use other “remedies”: direct monetary financing of the economy, centralized financial supervision, harmonized regulation, and executive decisions without democratic consent.

Freedomly-patriotic alternatives in EU economic and monetary policy?

Is there an alternative to these “other means”?

Yes. In fact, there are several alternatives.

There are alternatives within the existing framework and there are alternatives outside and parallel to the EU.

While personally I am not opposed to leaving the euro area and the EU, I still believe that the current system can be improved.

Firstly, we could enforce the SGP by imposing sanctions on countries that break fiscal rules. However, this would most likely trigger an immediate Italian exit from the euro area.

Secondly, we could normalize interest rates and default Italy, Cyprus and Greece and half of the largest EU banks. This would of course be painful and would lead to a huge economic correction but would benefit the health of the European financial market in the long term. It would also make macroeconomic harmonization less urgent.

Thirdly, we could also demand the national banks to apply prudent policies by urging them to repatriate and increase their gold reserves. Gold has always been a good insurance policy against monetary uncertainty. Just recently, the Bundesbank began repatriating its gold from the UK and Canada for the first time since the euro was introduced. This means that the Bundesbank is also preparing for the worst.

There are also several alternatives outside the existing framework.

Firstly, you could propose an active withdrawal from the EU. Of course, outside of Article 50, there are no rules for this scenario, yet Brexit is an interesting test case. The resignation of a member state from the euro area would of course be much more difficult.

Secondly, another alternative would be a passive withdrawal from the EU or euro area. This could mean allowing currency competition within a member state. The Lega came up with such a proposal called Mini-BOTS. One could also allow cryptocurrencies and foreign currencies such as British pounds or US dollars as legal tender. This, of course, would be illegal under existing EU rules, but the EU has no tools to enforce these rules. This would mean that consumers could spread their risk across different currencies that have legal value in consumer markets.

A third alternative would be a crash course. A so-called race to the bottom. This implies that the few financially strong member states like Austria and Germany would be imitating the economic policies of southern Europe. This means: more debt generation, higher budget deficits and lower taxes. In this case, the EU could no longer rely on German and Austrian taxpayers to bail out the other member states. With the increasing risk of having to save Austria or Germany, the southern Europeans would be the first to stop further European debt and transfer integration.

*Presentation given on 18 March 2022 in Vienna, Austria at the second module of the Europe academy of the Freedom Educational Institute (FBI).

One comment