_ Alexander Donges, lecturer, University of Mannheim; Jean-Marie Meier; assistant professor of Finance, University of Texas at Dallas; Rui Silva; Associate Professor of Finance, Nova School of Business and Economics. VoxEU. 20 May 2022.

A large part of the world operates under oligarchic and authoritarian regimes, where access to economic opportunities is not offered to all citizens. This analytical note discusses the impact of such ‘extractive institutions’ in stifling innovation and future economic growth. Using novel hand-collected data, it documents that ‘inclusive institutions’, which promote equal access to economic opportunities, are a first-order determinant of innovation. Geographical regions with more inclusive institutions are able to produce more than twice as much innovation (proxied with patents per capita) as regions with worse institutions.

What determines economic prosperity? In addressing this important question, a large body of research documents that the creation of new products and services as well as the improvement of existing production techniques is one of the most important determinants of economic growth (e.g. Mokyr 1992, Grossman and Helpman 1993, Kogan et al. 2017, Wu and Hao 2022). Indeed, many of the products and services that we most value today were not available even a few decades ago.

The local socioeconomic environment is crucial in determining the ability of individuals and firms to innovate, leading innovative activity to be clustered in regions where the local conditions are more conducive to innovation (Chatterji et al. 2014). As a consequence, local and national governments exert substantial effort and devote large amounts of resources in designing and implementing policies with the aim of fostering innovation. For example, in 2015 the White House’s Strategy for American Innovation stated that “[n]ow is the time for the Federal Government to make the seed investments that will enable the private sector to create the industries and jobs of the future, and to ensure that all Americans are benefitting from the innovation economy” (National Economic Council and OSTP 2015).

In a new paper, we study the role of inclusive institutions in creating an environment that is conducive to innovation (Donges et al. 2022). We use the term ‘inclusive institutions’ (as opposed to ‘extractive institutions’) to refer to institutions that provide broad access to economic opportunities, instead of favouring the few at the expense of the many (North 1991 Acemoglu and Robinson 2012).

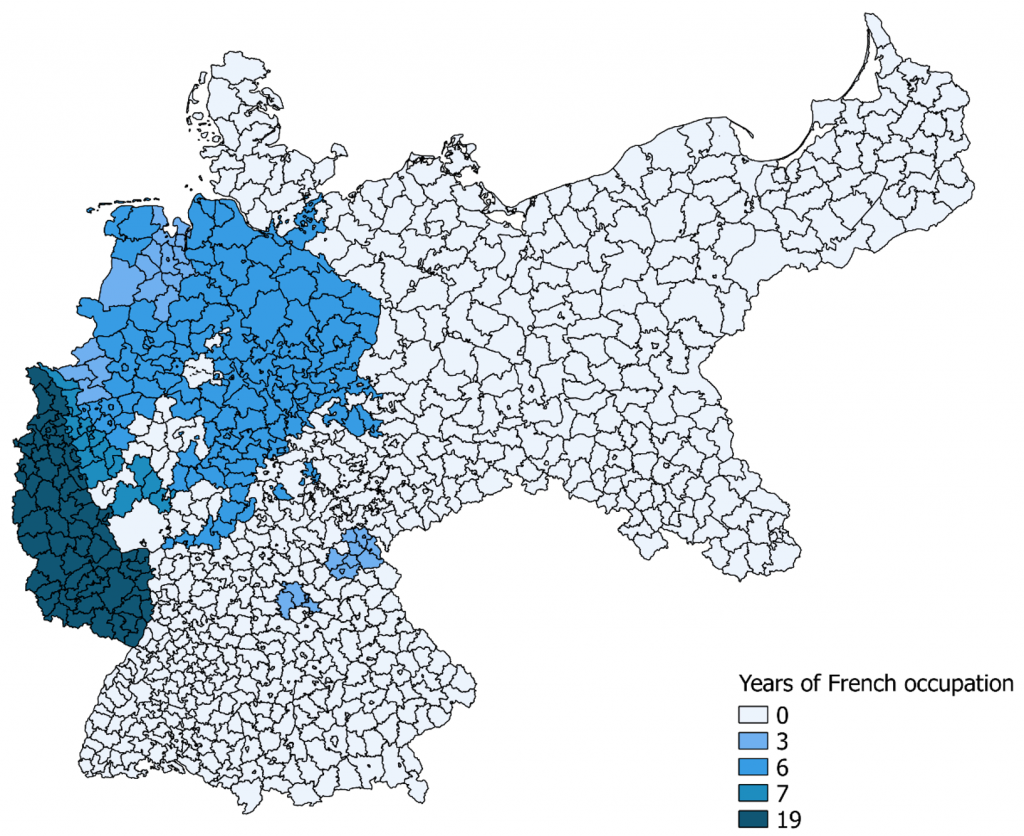

Studying this question empirically is challenging because some regions may have both better institutions and more innovation, but that does not necessarily mean that the former causes the latter. To test whether the implementation of more inclusive institutions subsequently leads to more innovation, we study a historical setting: the early adoption of inclusive institutions in those parts of Germany that the French occupied after the French Revolution of 1789. Figure 1 shows the geographic dimension of the French occupation and its length.

Figure 1.

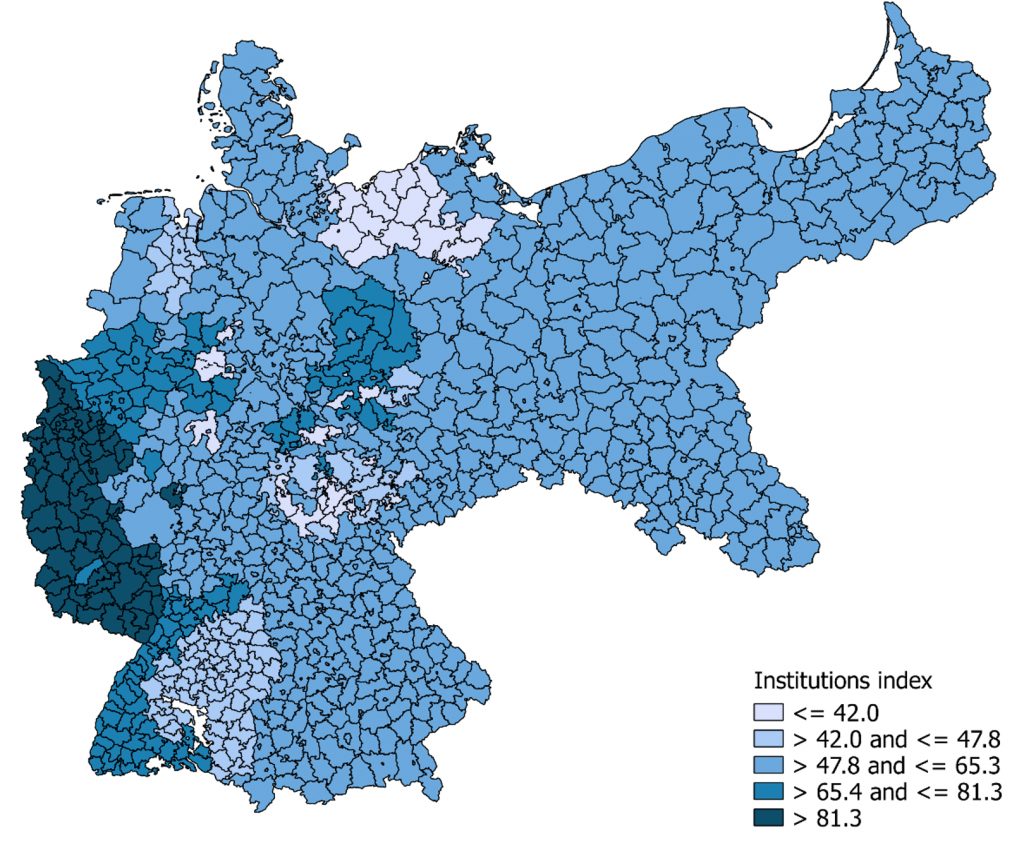

The inclusiveness of institutions is measured with an index including four major reforms that were implemented by the French to reduce the power of local German elites, including the dissolution of guilds, the introduction of the French Code civil, the abolition of serfdom, and agrarian reforms (Acemoglu et al. 2011). These reforms created a more level playing field in terms of economic opportunities, by lowering entry barriers and reducing distortions in labour and product markets. Figure 2 shows the regional differences in the inclusiveness of institutions based on the institutions index, which measures the number of years the aforementioned institutional reforms have been implemented in each German county. The map illustrates that in the Rhineland, the region with the longest period of French occupation, the index of institutions has the highest values due to early reform implementation.

Figure 2.

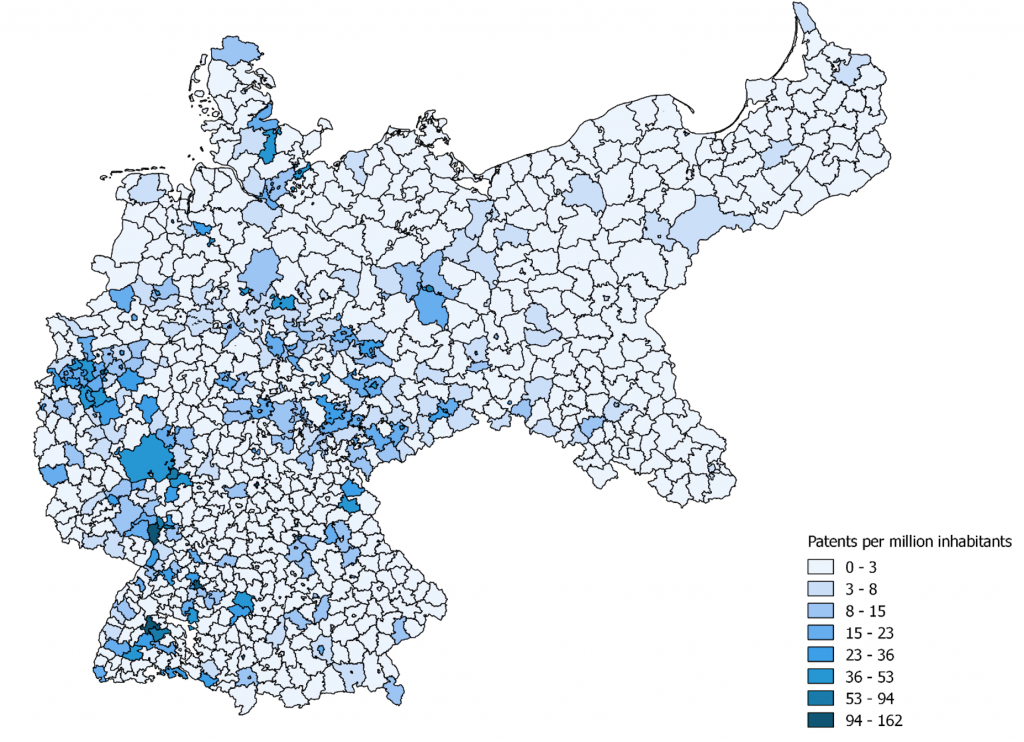

We test whether locations with more inclusive institutions due to the French occupation subsequently produced more high-value patents per capita, which we use as our main proxy for innovation. Figure 3 shows the spatial distribution of patenting activity.

Figure 3.

Importantly for our study, the motives behind the French occupations were military and geostrategic, not economic. Napoleon wanted to expand the French borders to create a territorial buffer between France and its rivals, Austria-Hungary and Prussia. This means that the French did not simply chose to occupy the German regions with the highest potential for future innovation. This argument is underlined by the fact that, after the French defeat, Prussia wanted to annex the Kingdom of Saxony, which was at the time considered one of the most prosperous German regions, with high potential for economic growth. However, the United Kingdom and Austria-Hungary did not want to give such an economic powerhouse to Prussia. Therefore, it was agreed that Prussia would annex the Rhineland and Westphalia. These regions were seen by the rulers of the time to be economically less promising, but they had implemented inclusive institutions early due to the French occupation.

We show that, in counties with more inclusive institutions due to the French occupation, there were significantly more patents per capita around 1900. The magnitudes of the estimated effects are sizeable. In the baseline specification, we find that counties with the longest period of French occupation, which implemented better institutions earlier, had more than twice as many patents per capita around 1900 as unoccupied counties with more extractive institutions. To ensure that the results are not due to the occupied regions being (even if only by chance) those with the most potential to innovate, we exploit the granularity of our hand-collected data to account for potential alternative explanations. Importantly, we find that the results are not driven by differences in local economic development.

We also test whether the French occupation fostered innovation through channels other than institutions, including culture and knowledge transfer, trade and market integration, the presence of intellectual elites, income inequality, access to finance, or differences in patent laws. However, even after controlling for a large number of potentially confounding effects, the picture that emerges is one where inclusive institutions have a central role in promoting innovation.

Since our analysis relies on patents to measure innovation, the concern may arise that better institutions may have led to increases in patenting even if there was no change in the level of innovation. This could have happened because in locations with better institutions courts may have worked more efficiently, making the legal protection provided by patents more effective. To show that our results are about innovation and not just patenting, we collected data on innovative products exhibited at two world’s fairs (1876 and 1893) as a non-patent-based proxy for innovation. Using this alternative proxy for innovation, we continue to find a significantly positive effect of institutions on local innovation output.

In tracing the implications of our findings for economic growth, we show that the effect of inclusive institutions was particularly pronounced for innovation in chemicals and electrical engineering, which were the two high-tech sectors of the second industrial revolution (Mokyr 1992; Landes 2003).

We study the determinants of innovation in the German Empire, since this historical setting provides us with variation in institutional quality within a single country. However, the results of our study may have broader implications for the understanding of the determinants of innovation. Even today, countries might be able to stimulate innovation by creating a more inclusive and efficient legal system with lower transaction costs. According to the 2021 Democracy Index report by the Economist Intelligence Unit, “less than half (45.7 percent) of the world’s population now live in a democracy of some sort, a significant decline from 2020 (49.4 percent).” Our findings suggest that the lack of inclusive institutions in large part of the world means that much of the world’s potential for innovation is left untapped (see also Bekkers and Góes 2022 for a discussion of how geopolitical conflict can affect innovation).

Our findings also suggest that reforms and policies aiming to increase competition and to create a level-playing field could be especially beneficial for innovation, even in developed countries. As with guilds or trade licenses in Imperial Germany, today there are institutions such as occupational licensing that restrict competition. Lifting such restrictions may foster innovation.

In the early 19th century, Germany was economically and technologically backward compared with other countries in Western Europe. However, by the end of the century, Germany had become one of the leading industrial countries with highly innovative and internationally competitive companies, in particular in the high-tech industries of chemicals and electrical engineering. In this regard, developing and emerging economies may find it highly beneficial to implement the type of inclusive institutions that we study in our paper, as doing so could make them more innovative and help them catch up to the technological frontier.

References

Acemoglu, D and J A Robinson (2012), Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty (1st ed.), New York: Crown.

Acemoglu D, D Cantoni, S Johnson, and J A Robinson (2011), “The Consequences of Radical Reform: The French Revolution”, American Economic Review 101(7): 3286–3307.

Bekkers, E and C Góes (2022), “The impact of geopolitical conflicts on trade, growth, and innovation: An illustrative simulation study”, VoxEU.org, 29 March.

Donges, A, J Meier,and R Silva (2021), “The Impact of Institutions on Innovation“, Management Science, forthcoming.

Grossman, G M and E Helpman (1993), Innovation and Growth in the Global Economy, MIT press.

Kogan, L., D Papanikolaou, A Seru, and N Stoffman (2017), “Technological Innovation, Resource Allocation, and Growth”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132(2): 665-712.

Landes, D S (2003), The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present, Cambridge University Press.

Melitz, M and S Redding (2021), “Trade and innovation”, VoxEU.org, 28 July.

Mokyr, J. (1992), The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress, Oxford University Press.

National Economic Council and OSTP – Office of Science and Technology Policy (2015), A strategy for American innovation, White House.

North, D C (1991), “Institutions”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 5(1):97-112.

Wu, H X and J X Hao (2022), “China’s other challenge in growth: Investment in intangible assets”, VoxEU.org, 17 April.

* Republished from the original publication on VoxEU in accordance with their copyright rules.