_ Laurie DeRose, senior fellow, Institute for Family Studies; assistant professor, Catholic University of America. 26 June 2023.*

When my husband I bet against each other, the stakes are usually a volcano roll from the Japanese restaurant less than a mile from our house. I’d bet a volcano roll that most Americans know that Japan is unfriendly to immigration, despite its low birthrate. I’d also bet a goulash supper coupled with a chimney cake dessert that most Americans are unaware that Hungary could be described the same way.

If I had to bet which country is poised for better trends in the coming decade, I’d go with Hungary for three reasons. 1) Hungary’s marriage and divorce trends are good for the economy and for children, 2) its birth rate has recovered somewhat, and 3) the tension between its anti-immigration policy and other facets of its national character may undermine internal support for the policy.

Family Trends

Nationalist Prime Minister Viktor Orban has introduced a number of tax benefits and other programs to favor married families. For instance, couples marrying before the bride’s 41st birthday will be loaned about $33,000, and the loan doesn’t even have to be repaid (depending on the number of children born to the marriage). By the end of 2019, the consensus was that the policies had in fact promoted marriage.

I verified that the marriage rate doubled from 2010 to 2021 (whether calculated per 1,000 population or per 1,000 unmarried women). Both the foreign press and academics were skeptical about whether the marriage boom would spark a Hungarian baby boom (see Lyman Stone’s analysis here), but there is no denying the new popularity of marriage in Hungary.

More recently, however, devastatingly high inflation (currently 24 percent, partly attributable to last year’s drought, the worst in well over a century) has done something that even COVID did not: reversed the upward trend in Hungarian marriage rates.

I can’t prove that marriage gains from over the last decade won’t be wiped out in the next, but I am not among the skeptics, like some reputable demographers at the Hungarian Demographic Research Institute. Senior research fellow Livia Murinko thought the marriage boom would have ended even without the inflation crisis because “Nearly anyone who could potentially get married has already done so.” Balázs Kapitány ascribed the marriage boom primarily to shotgun weddings, noting that the large interest-free loan available to newly married couples was likely an insufficient marriage incentive for childless couples because they would have to pay back a substantial portion with interest if they did not have a child. In contrast, the loan and marriage were worth taking up for already pregnant mothers. Perspectives like these are focused on cost-benefit analysis of Hungary’s family policies, without considering that the policies could have indirect effects by reshaping the culture.

The United States and other developed countries have transitioned from a time when marriage was the cornerstone of adult life to an era where marriage is better described as a capstone: the crowning achievement of a successful adulthood. The new marriage incentives in Hungary are structured so that marriage can again be an integral part of the building process. By making marriage economically beneficial, the Hungarian government may have helped alter the cultural image of marriage from a means of showcasing security to a means of building it. The Hungarian constitution certainly aims to make marriage culturally normal.

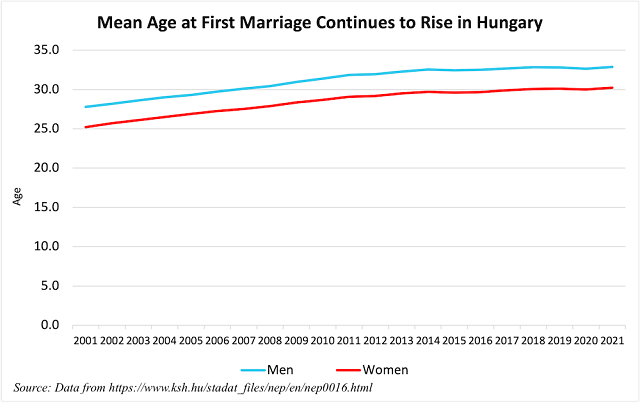

Without cultural changes, the skeptics would be right. While it is too early to tell, I argue that two other marriage-related trends from over the last decade auger well for Hungary’s marriage rates recovering from their current inflation-related stupor. First, divorce rates have been falling: Divorces per marriage have halved since 2010. If financial incentives were luring ill-suited couples into marriage, divorce rates should have been stable or increasing. Instead, the stability of Hungarian marriages may reflect growing cultural support for the institution. Second, the age at first marriage has continued in its slow upward trend.

Hungary has become more marriage-friendly without an uptick in younger marriages that carry a higher risk of instability. This lends credence to my position that a simple cost-benefit perspective is insufficient for predicting whether Hungary’s marriage boom has fizzled. Its trends support stable marriage, not just marriage.

Birth and Abortion Rates

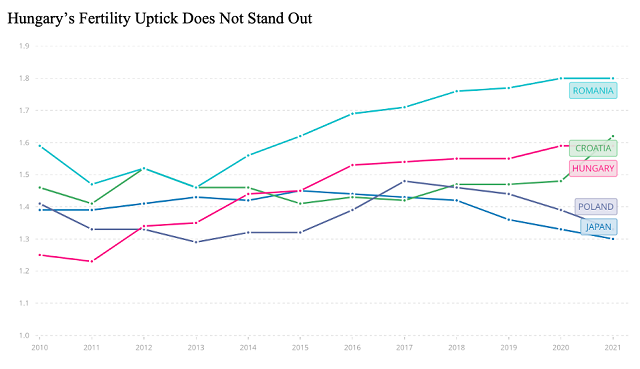

Hungary’s total fertility rate has recovered from what demographers call “lowest low fertility” (below 1.3 children per woman) over the same period as its marriage boom.1 While the country does not stand out as a unique success story among its neighbors with respect to fertility recovery, Japan has dropped into lowest low fertility levels while Hungarian women now average more than a child and a half.

Source: Data World Bank

Abortion occurs at half the rate it did in Hungary in 2003, and it seems unrelated to the teen birth rate. For example, there was no decrease in teen abortion from 2011-2016 while teen birth rates were rising, and both the teen abortion rate and the teen birth rate in Hungary have fallen since 2016.

Immigration

The 2010 and 2013 revisions to the Hungarian constitution aim to reinforce native Hungarian character, including its Christian heritage. From start to finish, the document is deeply nationalist and socially conservative. Hungary is not at all unique in trying to make “deeply nationalist” fit under the Christian umbrella. Perhaps the most egregious historical example is that of the Dutch Afrikaners in South Africa who experienced the Great Trek through which they settled apart from British South Africans as a migration to the Promised Land. Historian Mordechai Tamarkin has described Afrikaner “Christian-nationalism” as an oxymoron because “Christianity represents universal values, whereas nationalism focuses on the particular identity and interests of a particular group.” Tamarkin’s Afrikaner history focuses on the Dopper intellectuals who—earlier than the Dutch Reform Church in South Africa more generally—found themselves having to reject apartheid-tainted nationalism to be consistent with their Christian beliefs.

Politically, “deeply nationalist” and “socially conservative” can be reconciled into a recipe for demographic recovery through fertility rather than immigration. In Hungary’s case, however, they are trying to reconcile “deeply nationalist” with Christian. It has been done before—Joan of Arc passionately believed that God favoured the French — but the inherent contradiction between Christian and nationalist make Hungary’s course problematic. The Judeo-Christian scriptures mandate love of the immigrant as part of holy living. Therefore, I predict that Hungary will have a harder time than Japan at staying unwelcoming to immigration.

In sum, Hungary’s pro-marriage culture seems robust enough to survive given the increased age at marriage and the decline in divorce. This should continue to support Hungary’s recovering birth rate, and opposition to immigration is more likely than not to wane. Overall, these are healthy trends.

* Republished from the original publication with the Institute for Family Studies.