_ Matthias Diermeier, Personal Research Assistant of the Director, IW Cologne; Dr. Thomas Obst, Personal Research Assistant of the Director, IW Cologne. Translated into English by Yuri Kofner. Cologne, 2020. Published for debate.

China bought its geopolitical rise dearly. But the corona crisis at the latest shows that the massive investments on the Silk Road are extremely risky. Not only are many countries stuck in a Chinese debt trap, China also needs a strategy for servicing its loans during the crisis. Loan defaults could put the mega project in trouble.

The rapid rise of the Chinese economy to become the industrial hub of the world economy has not remained without consequences for its competitors. Even in this country, where China has long been wooed for the promise of new sales markets, the mood has turned. The European investment screening and the ongoing discussion about a new industrial policy reflect the fears of the increasingly aggressive Chinese foreign trade policy. And especially in the Corona crisis, concerns about (state-subsidized) takeovers by Chinese investors are rampant in Europe. The mood in the USA has long since been openly critical of China and is even putting pressure on allies to exclude Chinese competitors from their markets. Security or competition policy concerns are cited as arguments.

The following applies: While China’s increasing role in global value creation and world trade is well known, growing capital exports and their financing are still under-highlighted. Even the private debt in China is difficult to quantify. In 2018 this was estimated at more than 160 percent of GDP. The loan approval process by China abroad is even less transparent; There are hardly any official data sources. There is little aggregated data from international databases and the Chinese government itself does not report on its international funding projects. Compared to other large economies, the external loans are all granted by state-run banks. Thus, these loans fly under the radar of the rating agencies. These restrictions make it difficult to locate cross-border capital flows.

In the lively discussion about the level of Chinese investment in emerging and developing countries (The Economist, 2020), a recent study shows that China has become one of the world’s most important lenders over the past two decades, with outstanding credit claims exceeding 1.5 Percent of global output (Horn et al., 2020). The sum of the outstanding loans to China in the emerging and developing countries exceeds the aggregated debt held by the Paris Club governments. In this body, loans that have got into trouble are traditionally negotiated, in which established economies act as creditors.

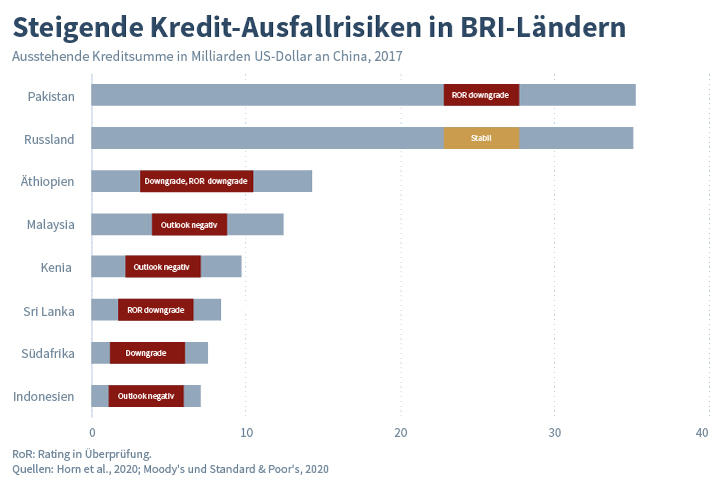

Large parts of the Chinese capital export stem from the mammoth project that the government decided to undertake in 2013 in the context of demographic aging, slowing domestic migration, declining income from infrastructure investments and declining competitiveness of exports in the manufacturing sector: the new Silk Road or Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (Johnston, 2018). In comparison with the volume of the Marshall Plan (USD 130 billion, at today’s prices), which contributed to the reconstruction of devastated Europe in the post-war period, the importance of the BRI becomes clear: According to the original plan, China is aiming for high investments in the countries involved from USD 890 billion (The Economist, 2016). These projects are financed by specially created or upgraded institutions, some of which have already gained experience with corresponding projects. The Export-Import Bank of China (Eximbank), together with the China Development Bank and other Chinese banks, issued loans with a total volume of USD152 billion to African countries between 2000 and 2018 alone (Acker et al., 2020). According to the latest figures from the World Bank, China now holds around 17 percent of Africa’s public debt. The Chinese Debt Trap Diplomacy has become the household word of the corresponding dependence of many countries on China (Brautigam, 2020). Even among the large BRI states, Pakistan, Ethiopia, Kenya, Sri Lanka and Belarus are some countries in which Chinese debts account for 10 percent or more of national GDP. These dependencies are associated with Chinese influence, but also with a corresponding risk. In relation to the African continent, the statistics already show a considerable amount of credit defaults (Acker et al., 2020). China had to accept debt relief in Africa as early as 2000.

Further risks arise from the crisis in emerging and developing countries caused by Covid-19 (Beer, 2020). Many foreign investors have withdrawn their capital from these countries. Current estimates assume a capital flight of around USD 83 billion in March 2020 alone – with the corresponding implications for the respective exchange rates. Chinese creditors hold 25 percent of the debt in these countries (Horn et al., 2020).

In view of the high investments in the context of the new Silk Road, China faces structural challenges with its foreign investments. There is evidence that until 2017, Chinese creditors accumulated outstanding claims on BRI countries amounting to USD 215 billion – the equivalent of around 1.5 percent of the rapidly growing Chinese GDP. In 2000, that figure was a negligible USD 0.64 billion; In 2013 it was already around USD 131 billion (around 1.4 percent of GDP). The economic upheavals of the last few months have made risky investments even more insecure. In a total of 29 BRI countries, the issuer rating was downgraded by one of the three major rating agencies (Moody’s, Fitch, S&P) either in the actual rating or in the outlook in 2020. In the case of the largest BRI debtor, Pakistan (USD 35 billion), the rating, which is currently classified as “highly speculative”, is shaky. Ethiopia, whose Chinese debt amounts to more than USD 14 billion, has already been downgraded from B1 to B2 within the same risk class. The total deterioration in creditworthiness along the Silk Road affects at least USD 119 billion – due to data gaps, the actual sum is estimated to be much higher. In addition, further devaluations are likely to follow.

While it is argued that there is no cause for concern about the high Chinese debt (e.g. due to the high domestic savings rate), one thing must be clear: China’s growth model is strongly driven by credit expansion; its investments are highly risky. Added to this is the collapse in growth in the first half of the year and the associated need for a gigantic economic stimulus package. Due to the existing debt overhang and the associated credit risks, this time the Chinese government has chosen the path of fiscal policy instead of renewed credit expansion as in the financial crisis of 2008 (Huang / Lardy, 2020).

This makes it clear that more than “just” billion-dollar investments are at stake for China. On the Silk Road, the structural decision must be made to write off, restructure, or refinance loans. Behind this, however, is the question of the sustainability of the Chinese growth model. China might turn out to be paying a heavy price for its geopolitical rise.

Literature:

Acker, K. / Brautigam, D. / Huang, Y., 2020, Debt Relief with Chinese Characteristics, Policy Brief, Nr. 46: China Africa Research Initiative

Beer, S., 2020, Die Corona-Krise in den Entwicklungsund Schwellenländern: Eine Katastrophe naht. IW-Kurzbericht, Nr. 57, Köln

Brautigam, D., 2020, A critical look at Chinese ‘debt-trap diplomacy’: the rise of a meme, in: Area Development and Policy, 5. Jg., Nr. 1, S. 1–14

Horn, S. / Reinhart, C. / Trebesch, C., 2020, China’s Overseas Lending, NBER Working Paper, Nr. 26050

Huang, T. / Lardy, N. R., 2020, China’s fiscal stimulus is good news, but will it be enough?, PIIE China Economic Watch

Johnston, L., 2019, The Belt and Road Initiative: What is in it for China?, in: Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 6. Jg., Nr. 1, S. 40–58

The Economist, 2016, Our bulldozers, our rules, Ausgabe 2.7.2016

The Economist, 2020, The poorest countries may owe less to China than first thought, Ausgabe 4.7.2020

Source: https://www.iwkoeln.de/