_ Yuri Kofner, economist, MIWI Institute for Market Integration and Economic Policy. Research paper for the Austrian FREILICH journal. Munich – Graz, 24. March 2024.

Executive summary

Despite a historically low unemployment rate of 2.9 per cent, German businesses are missing a record number of over 533,000 skilled workers, costing them between 2.1 and 2.5 per cent of GDP. Given current demographic trends, the skills gap is expected to rise to between 3 and 5 million unfilled vacancies by 2030, which will cumulatively reduce Germany’s growth path by 14 per cent over the 2020s.

Sectors with the highest relative skills shortages are social work, education, care, skilled trades, drivers and IT, as well as mechanical engineering and electronics in the medium term.

The severity of the skills gap is proportional to the level of skills required, i.e. the vacancy surplus rate for skilled workers is 40.8 per cent, for specialists 44.3 per cent and for experts almost 60 per cent of vacancies are unfilled. In contrast, there is an oversupply of over 1 million unqualified unskilled workers on the labour market.

Whether immigration can help to alleviate the shortage of skilled labour depends heavily on the country of origin. Immigrants from West and East Asian countries generally have a very high level of education and work qualifications, especially Chinese, Indians and Americans. These are also the population groups with the highest median incomes in Germany.

The opposite is true for immigrants, especially asylum seekers, from Africa and the Middle East, where between 55.5 and up to three quarters of people of working age have no vocational qualifications and 31 per cent do not even have a school-leaving certificate.

A similar picture emerges with regard to the fiscal impact of immigration on the national budget. Natives and immigrant groups from West and East Asian countries generally make a positive net contribution to the treasury, i.e. they generally pay in more taxes than they receive back in public services. In the case of immigrants and especially asylum seekers from Africa and the Middle East, the opposite is usually true: they cost the welfare state significantly more over their entire lives than they ever pay in taxes, as a large proportion of them are either unemployed (almost 30 per cent among immigrants from countries of asylum origin) or are employed in low-paid jobs with little or no qualification requirements, which contribute only very little taxes.

Although cheap labour migration does indeed exert a small negative wage pressure on native workers, the much bigger problem in the German case is that current immigration is mainly not into the labour market, but directly into the welfare system. One in four Hartz IV (Bürgergeld) recipients is a foreigner and half of all nationals of countries of asylum origin receive unemployment benefits.

Uncontrolled and irregular immigration is therefore absolutely the wrong way to tackle the shortage of skilled labour. Other measures such as state-imposed wage increases, longer working hours and greater labour market participation by women are also less suitable for alleviating the shortage of skilled workers – for various reasons that are explained in the study.

In the author’s opinion, more effective or, from a conservative point of view, more suitable measures would be:

- A downsizing of the state apparatus to the 2005 level, which could free up 166,000 largely well-qualified administrative staff.

- Incentives to stop and reverse the average annual net emigration of 46,600 highly qualified German citizens of prime working age (nearly 800.000 since 2005 until 2021).

- Introduction of a controlled immigration policy based on the Canadian, Australian, Japanese and Korean models, which primarily only allows the immigration of highly qualified net taxpayers according to the needs of the labour market (as well as students).

- A further-education and training campaign to raise the education and qualification level of the labour force already in Germany, especially the more than 1 million unskilled workers who are currently unable to find a job.

- Introduction of an activating family policy with generous tax benefits, housing measures and better childcare facilities. Limiting abortions to those with a medical or criminal indication (which account for only 5.6 per cent of all abortions) over 30 years alone would provide the economy with around 3.3 million new workers. And political incentives to increase the fertility rate of German women back above the replacement rate of 2.1 would increase the German population by 12.5 million people over the same period.

- Ultimately, Germany could also take the “Korean” or “Japanese” route by seeing the shortage of skilled workers not only as a problem, but also as an opportunity to counter demographic change with digitalisation and robotisation. Increased automation with current technologies could already reduce the demand for 1.4 million immigration-intensive low-skilled occupations such as cleaning, warehouse logistics, agricultural support services and food production.

Chapter 1. Skills shortage and immigration

Scope of the skills shortage

The German economy is suffering from a considerable shortage of skilled labour. This has been independently confirmed by various institutes, studies and surveys.

In December 2022, the number of vacancies for skilled workers reached almost 1.2 million, which is the highest level since 2011, according to surveys by the Cologne Institute for Economic Research (IW Köln). The skills gap, i.e. the number of vacancies for which there are no suitably qualified unemployed people, was just under 533,000.[1] According to estimates by the Institute for Employment Research (IAB), the total number of vacancies even reached almost 2 million – a record.[2]

According to an ifo survey, 43.6 per cent of companies surveyed in January 2023 stated that they would be affected by a shortage of skilled workers.[3] According to a survey by the German Chamber of Industry and Commerce (DIHK), more than half (53 per cent) of all companies stated in 2022 that they would not be able to find the necessary staff to fill vacancies.[4]

According to Prognos AG (2017), the skills gap is set to widen significantly in the future due to demographic ageing and despite the unprecedented immigration trend of around 200,000 immigrants per year: to 3 million unfilled vacancies by 2030 and 3.3 million by 2040.[5] A more recent survey by IW Köln from 2022 assumes that there could already be a shortage of 5 million qualified workers by 2030.[6]

Economic impact of the shortage of skilled labour

Given the current labour intensity of the domestic economic structure, the shortage of skilled workers is dampening long-term growth in Germany. According to studies by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), the economic growth lost in 2022 due to the shortage of skilled workers amounted to 2.1 (80.4 billion euros) to 2.5 per cent of GDP (97.3 billion euros).[7]

If the domestic economy does not increase its capital intensity (K) or its technological level (a), the intensifying shortage of skilled labour (L) will further exacerbate the loss of production in the future. The consulting agency Korn Ferry (2018) estimates the cumulative output loss due to the shortage of skilled workers at around EUR 525 billion by 2030, which corresponds to lost economic growth of around 14 per cent over the decade of the 2020s.[8]

Immigration as a solution to the skills shortage?

Interested political and economic lobby groups claim that increased immigration is necessary to solve the skills shortage. But is that true? For example, has the past immigration surge since 2015 helped close the record-breaking skills gap? In order to test this hypothesis, in this first section we compare the labor demand structure with the qualification structure of the native and immigrant population in Germany. In order to counteract the shortage of skilled workers, the qualification level of migrants, including asylum seekers, must correspond to the required qualifications of the job offers.

It should be noted at this point that the present analysis only deals with economic and fiscal aspects of the skills shortage in connection with migration. Other related important aspects such as legal issues, e.g. whether irregular migrants should be granted (easier) access to the labor market, as well as socio-cultural aspects or public safety issues are not addressed here.[9]

Structure of the labour demand

Research by IW Cologne shows that the following sectors are most affected by the shortage of skilled workers: social work, education and care, which make up five of the top ten occupations with a shortage, as well as crafts, drivers and the IT sector.[10] By 2026, mechanical engineering and the electronics industry will also be more severely affected by the deficit.[11]

More important than the classification by industry is the differentiation of the skilled worker shortage by level of qualification, where a positive connection can clearly be seen: In December 2022, the job surplus rate at the expert level was almost 60 percent (skilled worker gap: 154,000 jobs). The job surplus rate describes the proportion of open positions for which there are no suitably qualified unemployed people out of all open positions; For specialists this was 44.3 percent (skilled worker gap: 73,000 jobs), and for skilled workers it was 40.8 percent (306,000 jobs). In contrast, the unemployment surplus of helpers without vocational training amounts to almost 1 million people, which indicates a significant asymmetry in the labour market.[12] In other words, the domestic economy needs highly qualified experts, experienced specialists and well-trained skilled workers, but is saturated with unqualified unskilled workers, many of whom cannot or do not want to find work.

In the STEM professions in particular, which are of fundamental importance for maintaining Germany as an industrial location, the skills gap amounts to 325,290 unfilled vacancies.[13] “MINT” is a collective term for the educational fields of mathematics, information technology, natural sciences and technology.

Structure of the labour supply

Composition by ethnicity and nationality

In 2021, of the 82.3 million people living in Germany, only 59.7 million were Germans without a migration background. 22.6 million inhabitants had a migration background, of which 53 per cent were German citizens and 47 per cent foreign citizens.[14]

According to the Federal Statistical Office (Destatis), 446,000 net German citizens left Germany between 2015 and 2021, while 3,777,000 net foreigners moved to Germany.[15] Almost two thirds, around 61 per cent, of immigrants were asylum seekers.

In these seven years, most foreigners came from the following countries: Syria (630,774), Romania (386,956), so-called “unknown foreign countries” (226,421),[16] Afghanistan (217,452), Iraq (192892), Bulgaria (180,083), Poland (161,736), Croatia (150,987), Italy (145,671) and Turkey (106,869).[17]

Between 2015 and 2021, over 2.3 million asylum seekers came to Germany.[18] Of these, only 138,725 (6 per cent) were deported.[19]

Level of education

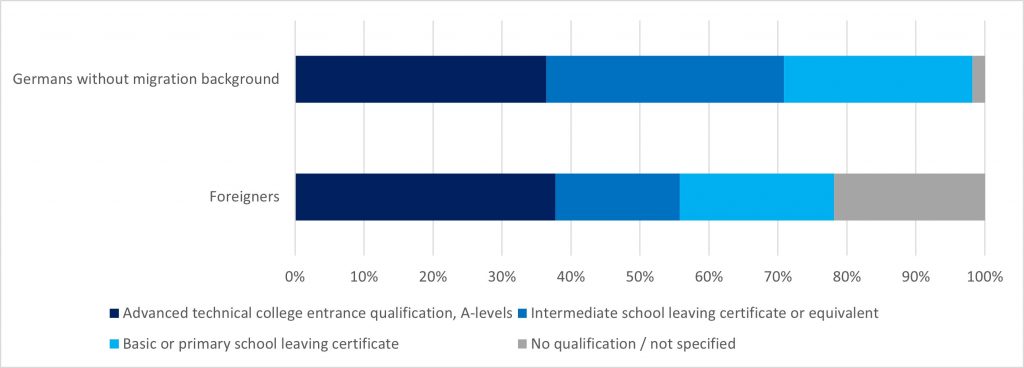

According to the Destatis microcensus, 36.4 per cent of Germans of working age without a migration background had a higher education entrance qualification or Abitur in 2021, a further 34.4 per cent had a Realschule or equivalent qualification, 27.3 per cent had a Hauptschule or Volksschule qualification and only 1.8 per cent had no school-leaving qualification.[20]

The level of education of foreigners of working age living in Germany was quite different: although 1.3 per cent more, namely 37.7 per cent, had a Fachhochschulreife or Abitur, only 18 per cent had a Realschule or equivalent qualification, only 22.4 per cent had a Hauptschule or Volksschulabschluss and over a fifth, a whopping 21.8 per cent, had no school-leaving qualification at all (Figure 1.).

Figure 1. Educational level of Germans without a migration background and foreigners living in Germany (2021)

Source: Own representation. Destatis (2021), Brücker H. et al. (2020).

According to an IAB study from 2020, only 11 per cent of asylum seekers of working age had a higher technical or university education before coming to Germany. Only a further 5 per cent had a qualification from a vocational training institution or dual training. 31 per cent of asylum seekers came to Germany without a school-leaving qualification. More than one in ten (11 per cent) had never even attended school.[21]

Level of professional qualification

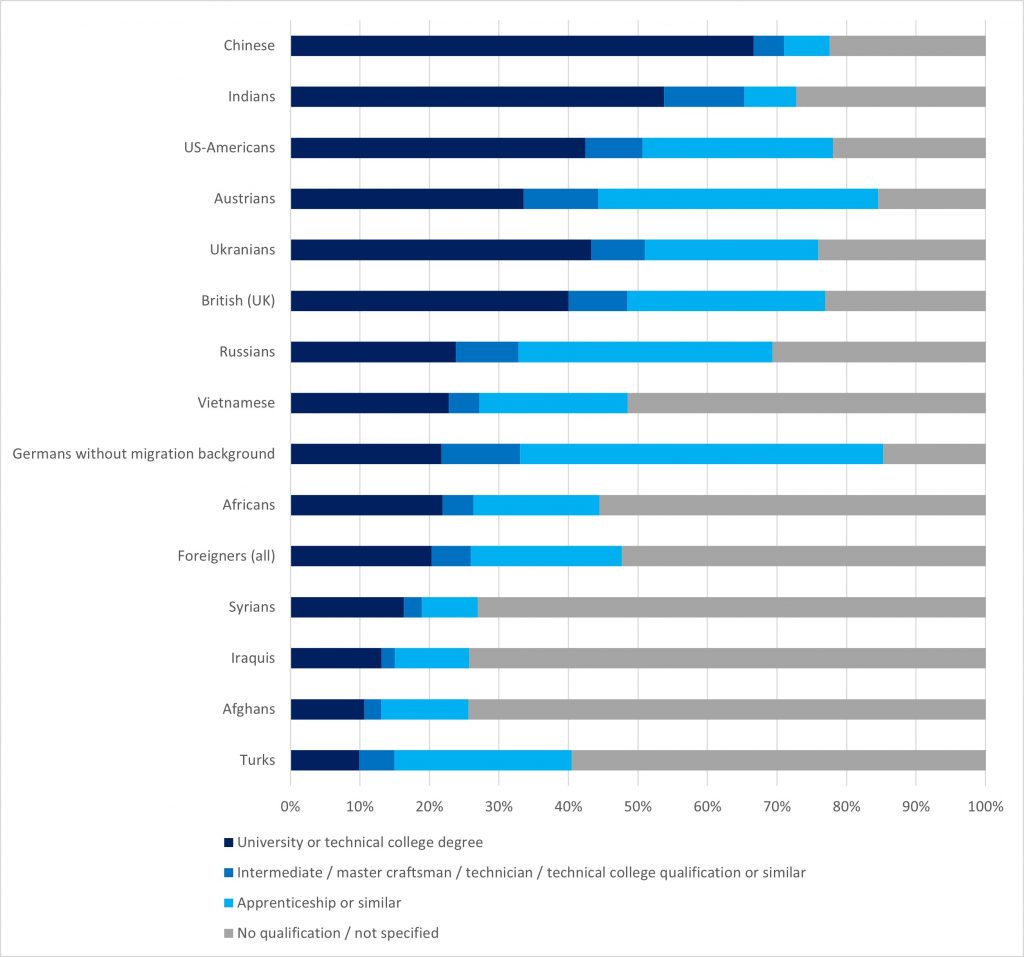

If we look at the level of professional qualification, the differences become even clearer: 21.7 percent of Germans without a migration background of working age had a higher professional or university degree, i.e. their level of education corresponded to the labour market demand for experts. The figure for foreigners was 20.3 per cent. 11.3 per cent of autochthonous Germans had a master craftsman, technician or technical college qualification or similar, i.e. which corresponded to the requirements of a specialist. The figure for foreigners was only 5.6 per cent. More than half (52.2 per cent) of the former had completed at least two years of training and were therefore equivalent to the level of a specialist, compared to only 21.7 per cent of the latter. And as many as 14.6 of employable native Germans had no vocational qualification at all, while more than half (52.5 per cent) of foreigners living in Germany had none.

Looking at the immigrant groups in detail, there are clear pan-regional differences in the level of labour market education between Western and East Asian countries on the one hand and countries in the MENA region (Middle East and North Africa) on the other.

The majority, namely 34 to 42.5 per cent of people from the USA, the United Kingdom and Austria living in Germany, had a qualification equivalent to the expert level. For many East Asians living in Germany, the proportion was even higher, e.g. over half (53 per cent) of Indians and two thirds (66.7 per cent) of Chinese had a higher professional or university degree.

Interestingly, a recent study by the IW Cologne shows that these are precisely the national groups in Germany with the highest monthly gross median earnings, with Indians in first place (just under 5,000 euros), followed by Austrians (4,716 euros), Americans (4,616 euros), Britons (4,537 euros), Chinese (4,331 euros) and so on. German citizens earn on average 3,643 euros gross per month, foreigners only 2,728 euros in total.[22]

At the other end of the spectrum, the vast majority of emigrants from the Middle East and Africa had no professional qualifications at all: 55.5 per cent of all Africans, 73 per cent of Syrians, 74.3 per cent of Iraqis and almost three quarters (74.4 per cent) of Afghans. Almost 60 per cent of representatives of the Turkish community in Germany also have no vocational qualification.

A similar picture emerges in the distribution between specialists and skilled workers among the immigration groups of the three regions mentioned above (Figure 2.).

Figure 2. Professional education level of Germans without a migration background and foreigners living in Germany (2021)

Source: Own representation. Destatis (2021).

Interim conclusion

The German labour market is oversaturated with unskilled unskilled workers, but at the same time there is a historic shortage of highly qualified workers with expert, specialist and skilled worker qualifications. In order to close the skills gap, the labour supply must meet these qualification requirements. Ideally, the proportion of unskilled workers without qualifications should therefore be very low and the proportion of academically or expertly trained workers high. In this respect, the analysis found considerable differences between the nationalities of different pan-regions.

Migrants from the MENA region, especially asylum seekers, are generally highly unsuitable for addressing the shortage of skilled labour, as these immigrant groups are predominantly under-qualified and unqualified. Alarmingly, this even applies to representatives of the Turkish community, who have been living in Germany since the 1970s and should actually have adjusted their level of qualification.

In contrast, immigrants from West and East Asian countries living in Germany are very well suited to cover the shortage of skilled labour, as they are generally highly qualified, even more so from the Far East than those from Europe and North America. Above all, they only burden the domestic economy to a small extent (between 22 and 27 per cent at most) with unqualified unskilled workers.

Although the proportion of academics and highly qualified people among Germans without a migration background is lower than that of West and East Asian immigrants, they – like Austrians – have a high proportion of trained skilled workers and a low proportion of unskilled workers.

When it comes to the question of whether immigration is conducive to remedying the German skills shortage, the empirically sound answer depends on the migrants’ region of origin, as this is primarily responsible for the qualification level of the (potential) immigrants. National migration policy should therefore set clearly differentiated rules that prevent the immigration of low-skilled and unskilled labour and facilitate the immigration of highly skilled workers as required.

Chapter 2 Welfare state and immigration

Impact of immigration on the public budget

Alongside the misleading narrative that immigration is useful to fill the domestic skills gap, which, as we have seen, depends heavily on the country of origin, is the argument that immigration benefits the economy as a whole. In the following second section, we will analyse this hypothesis indirectly by comparing the net fiscal effect of natives and immigrants on the public budget. The logic behind this: The higher the average labour force participation and income of a particular population group, the higher its tax contributions to the state compared to state social benefits. The ratio of both components results in the net fiscal effect for the public budget.

Unfortunately, German tax statistics only differentiate between nationals and foreigners, but neither between Germans with and without a migration background nor between migrants by country of origin.[23] Fortunately, such studies have been conducted in similar northern European countries – Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden – which can be used to draw comparable conclusions for Germany.

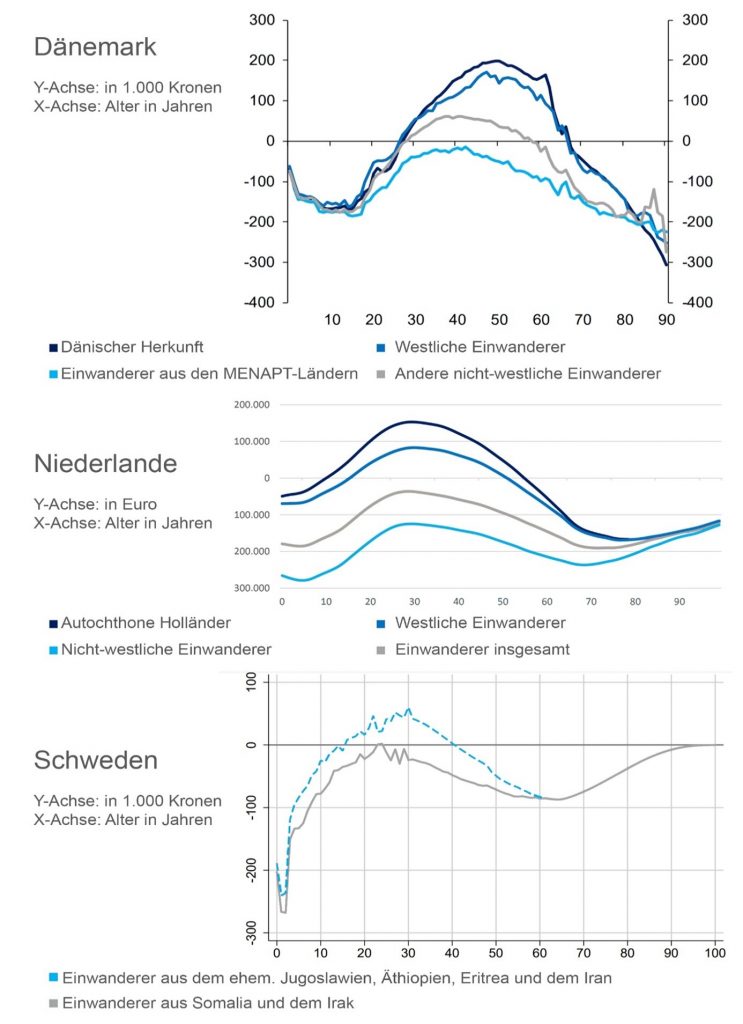

Denmark

In a 2021 study, the Danish Ministry of Finance analysed the net costs or net contributions of different population groups by nationality.[24]

Between 2014 and 2018, Danish citizens made an average annual net contribution to the public budget of 5.5 billion euros or almost 2 per cent of GDP. Immigrants from Western countries contributed an average net annual contribution of almost 1 billion euros to the national budget (0.3 per cent of GDP). At the same time, migrants from the MENAPT region (Middle East, North Africa, Pakistan and Turkey) caused average annual net costs to the national budget of EUR 3.6 billion or 1.3 per cent of GDP.

During the study period, the average Dane contributed 1,100 euros net per year to the budget. An average immigrant from the West generated 4,700 euros net annually, while a migrant from the MENAPT region cost the budget an average of 14,200 euros net annually. Migrants from Muslim countries accounted for 77 per cent of net spending on immigrants, according to the Royal Ministry of Finance. The immigrants who contributed the most to the Danish budget in net terms came from the UK, France, the Netherlands and the USA. However, immigrants from Far Eastern countries were also net contributors to Denmark’s public finances, including immigrants from India and China.

The Netherlands

A similar study for the Netherlands was conducted in 2021 by the University of Amsterdam on behalf of the Forum voor Democratie (FvD) party.[25] The researchers analysed microdata from 2016 provided by Statistics Netherlands and came to the following conclusions:

Only legal labour migration generates a positive net contribution to the Dutch budget of an average of 125,000 euros per immigrant over their entire lifetime. Study migration has an average net cost of 75,000 euros. Family reunification costs the household an average of 275,000 euros per immigrant.

The significant differences already known can also be identified by region of origin. Immigration from most Western and some East Asian countries has a positive fiscal impact. Above all, immigrants from neighbouring northern European countries, North America, the British Isles, Switzerland, Israel, Japan and Oceania make a significant positive contribution of around 200,000 euros per immigrant. Non-Western immigrants, on the other hand, cost almost 275,000 euros per person, with asylum migration in particular making a negative contribution with an average of 475,000 euros per immigrant. Migrants from Turkey, Morocco, the Horn of Africa and Sudan burden the national budget by 200,000, 550,000 and 600,000 euros respectively above their lifetime average. According to the study, native Dutch citizens are budget-neutral.

Interestingly, migrants from South Africa also have a positive net fiscal effect of 150,000 euros per person. Although not explicitly mentioned in the study, this could have to do with the return migration of white Dutch settlers (Afrikaans) back to the Netherlands.

Sweden

In a 2019 study by the University of Gothenburg for the Swedish Ministry of Finance, the fiscal consequences of accepting refugees for the Swedish budget were estimated.[26] Data from 2015 was used. Overall, asylum seekers cost the state budget a net 4.4 billion euros in 2015, which corresponds to one per cent of GDP. The annual net fiscal costs of refugees with the “best” labour market integration (former Yugoslavia, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Iran) amount to an average of 5,600 euros, while they average 9,900 euros for the cohorts with the least labour market integration (Somalia, Iraq). Over the life span (on average 58 years after arrival), this means average costs of 324,800 to 574,200 per refugee.

Interim conclusion and comparison with Germany

All three studies from Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden show that immigrants from West and East Asian countries generally make a positive net contribution to the national budget. On the contrary, immigrants from the Middle East and Africa in general are a significant net burden on the stately treasury, especially when they arrive as asylum seekers, as they receive far more in social security contributions than they ever pay back in taxes. Natives are either budget neutral or make a net tax contribution (Figure 3.). This fits in with the observation made above regarding cross-regional differences in education and qualification levels.

Figure 3. Net fiscal contributions and costs of natives and immigrants to the public budget

Source: Own presentation. Finansministeriet (2021), van de Beek J. et al. (2021), Ruist J. (2019).

As already mentioned, German tax statistics unfortunately do not differentiate between different population groups. However, available data on labour force participation and the receipt of social benefits suggest that the above statements on the different net fiscal effects very likely also apply to Germany.

According to the Destatis microcensus, the unemployment rate in 2021 was 2.6 per cent for Germans without a migration background, 6.2 per cent for Germans with a migration background and 7.6 per cent for foreigners.[27] According to the IAB, the unemployment rate for migrants from countries of asylum (Afghanistan, Eritrea, Iraq, Iran, Nigeria, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria, Ukraine) was 29.4 per cent in December 2021. Among EU citizens living in Germany, the rate was 7.9 per cent.[28]

In 2021, almost 46.7 per cent of Germans without a migration background earned the majority of their living from their own employment, while the figure was slightly lower among foreign nationals: 41.3 per cent.

While more than one in ten foreigners (10.6 per cent) were dependent on unemployment benefits I and II from the state (12.6 per cent among those with their own migration experience), only 2.6 per cent of native Germans were. A further 2.8 per cent of the former received “other state support” (excluding pensions and annuities), while the figure for the latter was 6.5 per cent (7.6 per cent among direct immigrants). According to a parliamentary enquiry by MP Rene Springer (AfD), the number of SGB II recipients (Hartz IV) who are foreign nationals doubled from 20 to almost 40 per cent between 2010 and 2021 – although it should be remembered that foreigners make up “only” 13.1 per cent of the total population.[29] According to the IAB Immigration Monitor, almost half (49.3 per cent) of nationals from countries of asylum origin were receiving SGB II benefits (Hartz IV) in December 2021.[30]

In his overview of the fiscal consequences of immigration to Germany between 1955 and February 2015, Moldenhauer (2018) came to the conclusion that immigration, particularly from non-European cultures, had a net negative impact on the welfare state.[31]

Wage dumping or immigration into the social system?

The question of whether immigration leads to wage dumping or even takes jobs away from natives is the subject of heated academic debate. However, the majority of academic literature on the US labour market points to a relatively low wage elasticity of immigration of around -0.1, i.e. if the number of migrants were to increase by 10 percent, wages would fall by an average of 1 percent.[32] Many studies find significantly more pronounced negative effects on the wages of less qualified native workers.[33]

However, this depends heavily on the current structure of the national and regional labour market. In Italy, for example, which has a high unemployment rate of around 10 per cent nationwide and up to 20 per cent in the Mezzogiorno region, it is politically necessary to get the country’s own unemployed into work first, rather than allowing further labour migration.[34] In Germany, however, the labour market situation is different, as we have seen.

The unemployment rate among Germans without a migration background is already very low at 2.7 per cent, while it is very high among asylum seekers at just under 30 per cent. This indicates that past and current migration flows into the domestic labour market have been less pronounced and therefore a possible wage dumping effect is less pronounced. Much more immigration into the German social system has taken place and continues to take place.

Chapter 3. Conservative skilled labour policy

Solutions to the skills shortage

Having established that the impact of immigration on the labour market and the welfare state depends largely on the country of origin, this third section discusses some possible policy measures to address the skills shortage. It should be noted that the list of policy measures presented is not exhaustive and is intended more as an advisory input into the debate from a right-wing conservative perspective.

Raising wages?

Recently, the president of the ifo Institute Clemens Fuest and the head of the Research Institute for the Future of Labour Simon Jäger suggested the simple but logical answer of simply paying higher wages where there is a shortage of skilled labour.[35] In fact, although nominal wages in Germany have risen by almost a quarter (24 per cent) in the last decade, real wages have fallen by an unprecedented 4.5 per cent between 2020 and 2022 due to coronavirus restrictions and the recent price explosion, which has wiped out the welfare gains made by the working population since 2015.

But “simply paying higher wages” as a response is not as easy and promising as claimed. First, nominal wage increases without real productivity growth will only be absorbed by current inflation and lead to further price increases in the future. Secondly, the already significant jump in the minimum wage from 10.45 to 12 euros per hour in 2022 has only further fueled inflation[36] and has not helped to close the skills gap, which, as we have seen, is primarily the more demanding positions with sufficient qualifications regards.

Third, wage increases would be a natural market signal from companies in response to labor shortages and would therefore not require further government intervention. The fact that this is not happening to the desired extent is less due to entrepreneurs’ contradictory interest in maintaining profits than to the increasing share of tax and bureaucratic costs in company expenditure. Since Angela Merkel (CDU) took office in 2005, the German tax and contribution ratio compared to GDP has increased from 34.4 to 39.5 percent in 2021 and has since been in the top third among OECD countries.[37] In 2021, payroll taxes and social security contributions accounted for 48.1 percent of the average single person’s labor costs, putting Germany in second place behind Belgium.[38] In 2017 (regrettably, Destatis stopped collecting data on this matter afterwards), statutory social costs and cost taxes accounted for between 4.1 and 5 percent of the cost structure of SMEs in the manufacturing sector in Germany.[39] In order to be able to pay higher wages, entrepreneurs should be relieved of tax and bureaucratic burdens. Labor market studies in Norway,[40] Finland[41] and Sweden[42] all found that lowering payroll taxes creates new jobs and, in some cases, increases wage levels.

Fourth, as economists at IW Cologne rightly point out, work is generally a service with inelastic substitutability.[43] For example, an untrained baker’s assistant cannot simply switch to a job as an IT specialist in automobile manufacturing just because it pays better. And no HR manager would allow that. A wage increase in shortage occupations would therefore only have a limited effect in a market situation where qualified workers are simply not available. First of all, sufficient retraining and upskilling of differently or unqualified workers would be required.

Finally, and this must also be said, Germany already has quite high unit labour costs in the manufacturing sector compared to international standards (7th place in 2021).[44] Further wage increases would further deteriorate Germany’s competitiveness.

Increasing working hours?

Another suggestion from employer-related institutes is, if you can’t find any additional suitable skilled workers, to “simply” increase the working hours of the existing skilled workers. In fact, between 2011 and 2021, the average number of hours worked per year per employee fell from 1,427 to 1,349, putting Germany at the bottom of the OECD countries.[45] However, Germany has higher labour productivity: in terms of GDP per hour worked, it is in the first third of the OECD countries.[46] Possible measures to increase working hours could include making working time limits and retirement ages more flexible. However, a reduction in public holidays would not reduce the skilled worker gap, but, on the contrary, would actually make it relatively worse.

Increasing the labour market participation of women?

Political interest groups and research institutes are pushing for greater participation of women in the labour market. They justify this not only by alleviating the shortage of skilled labour and increasing economic growth, but also see it as a step towards emancipation and “progress”.[47] In fact, aligning female labour market participation with that of men would bring 1.3 million (Germans without a migration background) to 2.4 million (total population) more women into the labour market.

On the contrary, conservatives view this critically – as an attack on traditional family values – and fear that it will accelerate the population decline. The conservative argument is that increased female labour force participation (FLFP), ceteris paribus, reduces the likelihood of a woman having children, thereby lowering a country’s total fertility rate (TFR). Thus, while measures to increase female labour force participation help to alleviate the current skills shortage, they could actually exacerbate it after 15-20 years if the children who are not born as a result have reached working age.

Empirical studies on this topic are very interesting. The following trends were identified for the OECD countries.[48] Initially, the correlation between FLFP and TFR was indeed strongly negative. In the 1980s, however, this relationship turned positive. Between 2005 and 2021, the fertility rate of German citizens rose from 1.3 to 1.5, even though the labour force participation rate of German women without a migration background increased from 70 to 81 percent over the same period.[49]

Researchers explain this both with more accommodating social attitudes towards working mothers and with increased political efforts to reconcile work and family life, e.g. with the help of child benefit and better childcare.[50]

However, there are two major caveats: The shift towards a positive correlation between FLFP and TFR generally only occurred after the TFR had fallen below the necessary replacement rate of 2.1. And this is still lower in the countries analysed. This means that the population of the developed countries is still shrinking, as is their respective labour forces. Furthermore, as far as the author can tell, previous studies have not taken into account the impact of immigration from cultures with traditionally higher fertility rates on the relationship under discussion. For example, the federal statistics do not differentiate between Germans with and without a migration background in the TFR, but only between citizens and foreigners as a whole.

Until these two questions have been better researched, the federal government, especially in the event of a possible conservative coalition, should not prematurely choose increasing female employment as a possible approach to solving the shortage of skilled labour.

A leaner state

A relatively simple and quick way to increase the supply of skilled labour would be to make civil servants and employees currently employed by the state redundant. Between 2005 and 2021, the number of public sector employees was inflated from 4.6 to 5.1 million. Of course, the author is not necessarily arguing in favour of cutting jobs in the public health and education sectors or in internal security. But one could, for example, make the more than 166,000 new, largely well-qualified administrative staff (“political management and central administration”) that have been added since 2005 available to the labour market again.[51]

Return of German emigrants

Before immigration is motivated by foreigners who would have to learn German, be integrated and possibly be trained, the federal government should think about incentives to stop and reverse the emigration of Germans. Up until the grand coalition (Union/SDP), the migration balance of German citizens to Germany was positive, i.e. more Germans came (back) to the Federal Republic of Germany than they left. But since Merkel took office, the migration balance has become negative: between 2005 and 2021, a net 792,633 Germans left their homeland.[52] According to a comprehensive survey by the Federal Institute for Population Research, around three quarters (73.4 percent) of these emigrants are Germans without a migration background and the urgently needed academics with a university degree (76 percent). Over two thirds (68.2 percent) of emigrants are in their prime working age between 20 and 40 years old. A total of 94.5 percent are of working age.

17.4 percent of emigrants cite “dissatisfaction with life in Germany” as the main reason for emigrating, but the majority are leaving for professional reasons (57.5 percent). Emigrants earn an average of 1,200 euros more after moving than before. The most important emigration countries are Switzerland, the USA, Austria and the United Kingdom.[53],[54]

The question of how best to stop and reverse the brain drain is complex and cannot be solved by any single incentive alone, as it ultimately affects Germany’s competitiveness as a centre of business and life. However, the study mentioned above suggests that high tax levies are a significant disincentive for attracting highly skilled labour. As mentioned above, Germany has the second highest tax burden on labour in the world. The German government could therefore consider lowering the average payroll tax burden to the level of the US and the UK of no more than 30 per cent.

Qualified immigration

After favouring the return of German emigrants, the federal government could also, if necessary, consider measures to attract suitable foreign skilled workers. These should be selected according to criteria that they have the appropriate professional qualifications, are likely to provide a net fiscal benefit to the public budget and are relatively easy to integrate into German society. As we have seen in the first and second parts of our analysis, these generally come from West and East Asian countries. Of course, it would be one-sided to design immigration policy solely on the basis of nationality, as there are also low-skilled workers among every national immigration group who do not meet the requirements of the labour market and generate costs for the welfare state. Therefore, as already mentioned, Germany should implement a controlled immigration policy based on qualifications, integration and the labour market.

Increasing the educational level

According to the PISA tests, the skills of German students have been falling continuously since 2012 to 2018 (last survey) from 514 to 500 points in mathematics and from 524 to 503 points in natural sciences, which puts Germany only in the middle in an international comparison. Between the 2011/12 and 2021/22 academic years, the number of new MINT students at German universities fell by over 17 percent from 208,000 to 172,000. During the same period, the proportion of MINT graduates in the total number of high school graduates fell from 35 to 31.8 percent. Since Angela Merkel took office, the proportion of 30 to 34 year olds and 35 to 39 year olds with MINT vocational training has fallen continuously from 22.3-24 percent in 2005 to 16.3-18.3 percent in 2019.[55]

The number of master’s examinations passed in German crafts fell by 11 percent from 22,000 in 2005 to 19,600 in 2021.[56]

As stated at the beginning, the skills gap increases the higher the required level of education and professional experience, while at the same time there is an oversupply of 1 million unskilled workers. The federal and state governments should therefore design a new, aggressive education policy with programs to increase the educational level of the domestic workforce already in Germany. However, providing detailed recommendations in this area would be beyond the scope of the present study.

Welcome culture for children

As mentioned at the beginning, the shortage of skilled labour is largely due to demographic decline. The baby boom generation of native Germans is retiring and there are fewer and fewer young people to replace them. This is the current situation. However, this does not mean that this trend must necessarily continue in the future. Instead of taking it for granted, the German government should do everything it can to ensure the healthy reproduction of the German people to the extent necessary to meet the future demands of the labour market. An activating family policy is indispensable for this.

The empirical literature shows relatively clearly that, on the one hand, fiscal incentives – such as direct transfers, maternity benefits, interest-free mortgage loans for home ownership, tax allowances and family tax splitting, as well as better conditions in the pension system – and, on the other hand, improved childcare provision are among the most effective state economic instruments for increasing the birth rate.[57] As with education policy, a detailed assessment of each of these measures in terms of effectiveness, costs and feasibility is beyond the scope of this analysis.

In Germany, for example, there were just over 1 million abortions in the decade between 2012 and 2022. By 2040, these people could theoretically have reached working age. In the decade between 2003 and 2012, 1.17 million people had abortions in Germany and almost 1.32 million between 1993 and 2002.[58] This means that if there had been no abortions since 1993, apart from for medical or criminal reasons, which only account for an average of 5.6 per cent of all abortions, then the 3.3 million shortfall in skilled labour forecast by the IW Cologne in 2040 could theoretically have been easily closed without any immigration, i.e. with the country’s own fertility.

Between 1993 and 2021, over 21.3 million babies were born in Germany.[59] During this period, the total fertility rate (TFR) of German women averaged 1.33 (1.84 for foreign women living in Germany).[60] If the TFR had been 2.1 during this period, i.e. above the replacement rate, over 12.5 million additional children would have been born, who would theoretically have reached working age by 2040.

Digitalisation and robotisation

Finally, the increasing shortage of skilled labour could and should not (only) be seen as a problem, but rather as an opportunity for modernisation, as Ragnitz (2023) rightly points out.[61] As stated at the beginning, the price signals caused by this labour shortage could force the German production structure to shift from trying to increase the missing labour component (L) to a relatively greater use of capital (K) and technology (a). In other words, Germany could counter domestic demographic change not with the help of immigration, but by following the “Japanese” and “Korean” path of increased use of digitalisation, AI and robots. Japan, for example, has set itself the goal of replacing 2.4 million jobs with robots by 2030.[62]

According to the Bundesbank (2021), the average growth rate in labor productivity fell from 4.5 percent annually to less than 1 percent between 1975 and 2020. In addition to demographic deterioration, the main factors behind lower growth rates are declining growth in capital intensity and the structural change in the economy forced by climate policy, which shifts labor to less productive sectors.[63] By the way, various studies, e.g. from Denmark[64] and Germany,[65] have shown that the immigration of cheap foreign workers, ceteris paribus, dampens the adaptation rate of robots and thus reduces productivity growth at the company level.

In a previous study, the author estimated the effect of possible political measures to accelerate digitalization at an additional annual growth of 0.4 percent of GDP.[66]

Although conservatives criticize technology’s alienation of interpersonal relationships, in the face of a shrinking domestic labor pool, robotization can be viewed as a potential means of reducing the need for low-wage immigration. Countries with an aging population, such as Germany, are also better suited for robotization: researchers at Boston University (2018) found a slightly positive correlation between the introduction of robots and a higher proportion of middle-aged workers, as they tend to have higher wages have, making the introduction of robots more cost-effective.[67]

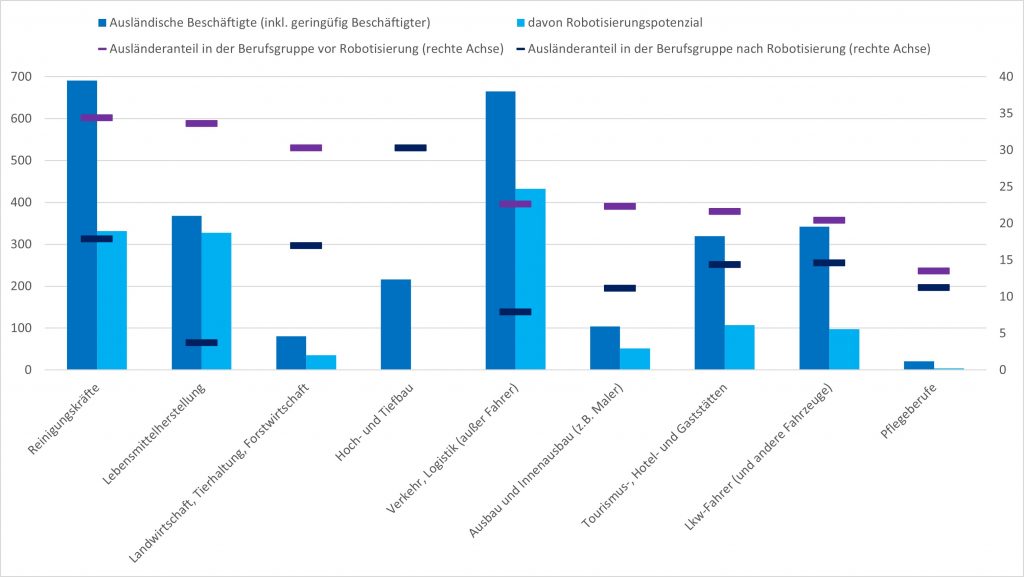

Even with the current level of robotic technology, it would be possible to offset a need for approximately 1.4 million foreigners currently employed in the various immigration-intensive low-skilled occupations such as cleaning, agricultural support, food production, warehouse logistics, etc. (Figure 4.).[68]

Figure 4. Robotization potential of immigration-intensive professional groups in Germany (2021)

Note: In 1,000 employees (left axis), in percent (right axis). Source: Federal Employment Agency, IAB, Federal Government (nursing professions).

Sources

[1] Köhne-Finster S., Tiedemann J. (2023). KOFA Kompakt 01/2023: Fachkräftereport Dezember 2022 – Fachkräftelücke trotz leichtem Rückgang auf hohem Niveau. IW Köln. URL: https://www.iwkoeln.de/studien/sabine-koehne-finster-jurek-tiedemann-fachkraeftereport-dezember-2022-fachkraefteluecke-trotz-leichtem-rueckgang-auf-hohem-niveau.html

[2] IAB (2023). IAB-Stellenerhebung. URL: https://iab.de/das-iab/befragungen/iab-stellenerhebung/aktuelle-ergebnisse/

[3] Sauer S. (2023). Mangel an Fachkräften entspannt sich leicht. ifo Institut. URL: https://www.ifo.de/pressemitteilung/2023-02-15/mangel-fachkraeften-entspannt-sich-leicht

[4] DIHK (2023). DIHK-Report Fachkräfte 2022. Fachkräfteengpässe – weiter steigend. URL: https://www.dihk.de/resource/blob/89404/584bdc687e6258d15f9228804a39e5d6/dihk-fachkraeftereport-2022-data.pdf

[5] WirtschaftsWoche (2017). 2040 könnten in Deutschland 3,3 Millionen Fachkräfte fehlen. URL: https://www.wiwo.de/politik/deutschland/studie-warnt-vor-enormem-fachkraeftemangel-2040-koennten-in-deutschland-3-3-millionen-fachkraefte-fehlen/20257718.html

[6] Spiegel (2022). Bis 2030 könnten fünf Millionen Fachkräfte fehlen. URL: https://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/bis-2030-koennten-fuenf-millionen-fachkraefte-fehlen-a-a9dcf938-2156-4c98-9861-fc08a33c0439

[7] Wirtschafswoche (2022). Studie: Fehlende Arbeitskräfte kosten über 80 Milliarden im Jahr. URL: https://www.wiwo.de/politik/konjunktur/fachkraeftemangel-studie-fehlende-arbeitskraefte-kosten-ueber-80-milliarden-im-jahr/28732828.html | Harnoss J. et al. (2022). Migration Matters: A Human Cause with a

$20 Trillion Business Case. BCG. URL: https://web-assets.bcg.com/1a/d1/ed3e7b194e0599500621570f19d2/bcg-migration-matters-a-human-cause-with-a-20-trillion-business-dec-2022-3.pdf

[8] Handelsblatt (2018). Fachkräftemangel kostet deutsche Wirtschaft mehr als 500 Milliarden Euro. URL: https://www.handelsblatt.com/politik/konjunktur/nachrichten/studie-fachkraeftemangel-kostet-deutsche-wirtschaft-mehr-als-500-milliarden-euro/21250414.html | Korn Ferry (2018). The Global Talent Crunch. URL: https://infokf.kornferry.com/global_talent_crunch_web.html

[9] For example, on the cultural-religious aspect of continued mass immigration to Germany, see: Kofner Y. (2022). Islamization of Germany and Austria or Christian revival: status quo, outlook, and policy measures. MIWI Institute. URL: https://miwi-institut.de/archives/2461

[10] Hickmann H., Koneberg F. (2022). Die Berufe mit den aktuell größten Fachkräftelücken. IW Köln. URL: https://www.iwkoeln.de/studien/helen-hickmann-filiz-koneberg-die-berufe-mit-den-aktuell-groessten-fachkraefteluecken.html

[11] Burstedde A. (2023). Die IW-Arbeitsmarktfortschreibung. Wo stehen Beschäftigung und Fachkräftemangel in den 1.300 Berufsgattungen in fünf Jahren? IW Köln. URL: https://www.iwkoeln.de/presse/pressemitteilungen/alexander-burstedde-in-welchen-berufen-bis-2026-die-meisten-fachkraefte-fehlen.html

[12] Köhne-Finster S., Tiedemann J. (2023).

[13] Anger C. et al. (2022). MINT-Herbstreport 2022. URL: https://www.iwkoeln.de/studien/christina-anger-julia-betz-enno-kohlisch-axel-pluennecke-mint-sichert-zukunft.html

[14] Destatis (2021). Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund – Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2021. URL: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/Publikationen/_publikationen-innen-migrationshintergrund.html

[15] Destatis (2023). Wanderungen zwischen Deutschland und dem Ausland 1991 bis 2021. URL: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Wanderungen/Tabellen/wanderungen-alle.html

[16] The large number of immigrants categorised as “unknown abroad” symbolises the practice of many asylum seekers throwing away their passports before crossing the border illegally in order to avoid being returned.

[17] Destatis (2023a). Wanderungen zwischen Deutschland und dem Ausland: Deutschland, Jahre, Nationalität, Geschlecht. URL: https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online?operation=previous&levelindex=0&step=0&titel=Statistik+%28Tabellen%29&levelid=1678972187644&acceptscookies=false#abreadcrumb

[18] BAMF. (2023). Anzahl der Asylanträge (insgesamt) in Deutschland von 1995 bis 2023. Statista. URL: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/76095/umfrage/asylantraege-insgesamt-in-deutschland-seit-1995/

[19] Deutscher Bundestag. (2023). Anzahl der Abschiebungen aus Deutschland von 2007 bis 2022. Statista. URL: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/451861/umfrage/abschiebungen-aus-deutschland/

[20] Here and further: Destatis (2021).

[21] Brücker H. et al. (2020). Integration in Arbeitsmarkt und Bildungssystem macht weitere Fortschritte. IAB. URL: http://doku.iab.de/kurzber/2020/kb0420.pdf

[22] Plünnecke A. (2023). Inder, Nordeuropäer und Österreicher verdienen in Deutschland am meisten. IW Köln. URL: https://www.iwkoeln.de/studien/axel-pluennecke-inder-nordeuropaeer-und-oesterreicher-verdienen-in-deutschland-am-meisten.html

[23] See, for example, the following study: Holger H., Zimmermann K.F. (2014). Does the Calculation Hold? The Fiscal Balance of Migration to Denmark and Germany. IZA. URL: https://www.iza.org/en/publications/pp/87/does-the-calculation-hold-the-fiscal-balance-of-migration-to-denmark-and-germany

[24] Finansministeriet (2021). Økonomisk Analyse: Indvandreres nettobidrag til de offentlige finanser i 2018. URL: https://fm.dk/udgivelser/2021/oktober/oekonomisk-analyse-indvandreres-nettobidrag-til-de-offentlige-finanser-i-2018/

[25] van de Beek J. et al. (2021). Grenzeloze Verzorgingsstaat; De Gevolgen van Immigratie voor de Overheidsfinanciën. University of Amsterdam. URL: http://www.demo-demo.nl/files/Grenzeloze_Verzorgingsstaat.pdf

[26] Ruist J. (2019). The fiscal lifetime cost of receiving refugees. CREAM. URL: https://www.cream-migration.org/publ_uploads/CDP_02_19.pdf

[27] Mediendienst Integration (2022). Wie viele Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund sind arbeitslos? URL: https://mediendienst-integration.de/integration/arbeitsmarkt.html

[28] Brückner H. et al. (2023). Zuwanderungsmonitor. Februar 2023. IAB. URL: https://doku.iab.de/arbeitsmarktdaten/Zuwanderungsmonitor_2302.pdf

[29] Junge Freiheit (2022). So viel gibt Deutschland für ausländische Hartz-IV-Empfänger aus. URL: https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2022/hartz-iv-auslaender/

[30] Brückner H. et al. (2023).

[31] Moldenhauer J. (2018). Die Kosten der Zuwanderung in die BRD und nach Westeuropa – eine Meta-Analyse. Friedrich-Friesen-Stiftung. URL: https://www.friedrich-friesen-stiftung.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Die-Kosten-der-Zuwanderung-in-die-BRD-und-nach-Westeuropa.pdf

[32] See the meta-study: Peri G. (2014) Do immigrant workers depress the wages of native workers?. IZA. URL: https://wol.iza.org/articles/do-immigrant-workers-depress-the-wages-of-native-workers/long

[33] de Brauw A. (2017). Does Immigration Reduce Wages? Cato Institute. URL: https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/cato-journal/2017/9/cato-journal-v37n3-4.pdf

[34] Bonatti L. (2019). Is Immigration Necessary for Italy? Is it Desirable?, EconPol. URL: https://www.econpol.eu/publications/policy_report_17

[35] Fuest C., Jäger S. (2023). Gegen den Fachkräftemangel: Mehr Lohn als Mittel. FAZ. URL: https://www.faz.net/aktuell/karriere-hochschule/buero-co/gegen-den-fachkraeftemangel-mehr-lohn-als-mittel-18721012.html

[36] Link S. (2022). Erhöhung des Mindestlohns lässt Preise steigen. ifo Institut. URL: https://www.ifo.de/pressemitteilung/2022-09-09/erhoehung-des-mindestlohns-laesst-preise-steigen

[37] OECD (2023). Tax revenue in percent of GDP. URL: https://data.oecd.org/tax/tax-revenue.htm#indicator-chart

[38] OECD (2022). Taxing Wages 2022: Impact of COVID-19 on the Tax Wedge in OECD Countries. URL: https://doi.org/10.1787/f7f1e68a-en

[39] SMEs make up 97.7 per cent of all companies in the manufacturing sector. | Destatis (2019). Kostenstruktur der Unternehmen des Verarbeitenden Gewerbes. 2017. URL: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Branchen-Unternehmen/Industrie-Verarbeitendes-Gewerbe/Publikationen/Downloads-Struktur/kostenstruktur-2040430177004.html

[40] Ku, H. et al. (2020). Do place-based tax incentives create jobs? University College London. URL: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2019.104105

[41] Benzarti Y., Harju J. (2021). Using Payroll Tax Variation to Unpack the Black Box of Firm-Level Production. University of California. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvab010

[42] Saez E. et al. (2019). Payroll Taxes, Firm Behavior, and Rent Sharing: Evidence from a Young Workers’ Tax Cut in Sweden. University of California. URL: https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20171937

[43] Burstedde A., Werner D. (2023). Fachkräftemangel – keine einfache Lösung durch höhere Löhne. IW Köln. URL: https://www.iwkoeln.de/studien/alexander-burstedde-dirk-werner-fachkraeftemangel-keine-einfache-loesung-durch-hoehere-loehne.html

[44] Schröder C. (2022). Lohnstückkosten im internationalen Vergleich. Kostenwettbewerbsfähigkeit der deutschen Industrie in Zeiten multipler Krisen. IW Köln. URL: https://bit.ly/43EUXKp

[45] OECD (2022a). Hours worked. URL: https://data.oecd.org/emp/hours-worked.htm

[46] OECD (2023a). GDP per hour worked. URL: https://data.oecd.org/lprdty/gdp-per-hour-worked.htm

[47] See, e.g.: Merkur (2023). Familienministerin: Frauen als Lösung für Fachkräftemangel. URL: https://www.merkur.de/wirtschaft/familienministerin-frauen-als-loesung-fuer-fachkraeftemangel-zr-91857350.html

[48] Oshio T. (2019) Is a positive association between female employment and fertility still spurious in developed countries? Hitotsubashi University. URL: https://www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol41/45/default.htm

[49] Destatis (2023b). Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus. Statistische Bibliothek. URL: https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/receive/DESerie_mods_00000020

[50] Destatis (2023c). Zusammengefasste Geburtenziffern (je Frau): Deutschland, Jahre, Staatsangehörigkeit der Mutter. URL: https://bit.ly/3TPbDu6

[51] Destatis (2006). Personal des öffentlichen Dienstes. 2005. URL: https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/DEHeft_derivate_00007178/2140600057004.pdf | Destatis (2022). Personal des öffentlichen Dienstes. 2021. URL: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Staat/Oeffentlicher-Dienst/Publikationen/Downloads-Oeffentlicher-Dienst/personal-oeffentlicher-dienst-2140600217004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

[52] Destatis (2023).

[53] BIB (2019). Gewinner der Globalisierung Individuelle Konsequenzen von Auslandsaufenthalten und internationaler Mobilität. URL: https://www.bib.bund.de/Publikation/2019/pdf/Policy-Brief-Gewinner-der-Globalisierung.pdf

[54] Erlinghagen M. et al. (2021). The Global Lives of German Migrants. Consequences of International Migration Across the Life Course. BIB. URL: https://www.bib.bund.de/Publikation/2021/The-Global-Lives-of-German-Migrants.html;jsessionid=3E55D3CE517EBD1AD4CE12B0C57B02DA.intranet661?nn=1210466

[55] Anger A. et al. (2022). MINT-Herbstreport 2022. IW Köln. URL: https://www.iwkoeln.de/studien/christina-anger-julia-betz-enno-kohlisch-axel-pluennecke-mint-sichert-zukunft.html

[56] ZDH. (2022). Anzahl der bestandenen Meisterprüfungen im deutschen Handwerk nach Geschlecht von 1999 bis 2021. URL: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/244558/umfrage/bestandene-meisterpruefungen-im-deutschen-handwerk-nach-geschlecht/

[57] See: Fauske A. et al. (2020). Best economic policies to increase fertility in Western countries. Norwegian Institute of Public Health. URL: https://miwi-institut.de/archives/379 | Sobotka T. et al. (2019). Policy responses to low fertility: How effective are they? UNFPA. URL: https://www.unfpa.org/publications/policy-responses-low-fertility-how-effective-are-they | Pronzato C. (2017). Fertility decisions and alternative types of childcare. IZA. URL: https://wol.iza.org/articles/fertility-decisions-and-alternative-types-of-childcare/long | Sagi J., Lentner C. (2018). Certain Aspects of Family Policy Incentives for Childbearing. A Hungarian Study with an International Outlook. Budapest Business School. URL: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/11/3976

[58] Destatis (2023d). Schwangerschaftsabbrüche: Deutschland, Jahre. URL: https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis//online?operation=table&code=23311-0001&bypass=true&levelindex=0&levelid=1678980049534#abreadcrumb

[59] Destatis (2023e). Lebendgeborene: Deutschland, Jahre, Geschlecht. URL: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Geburten/Tabellen/lebendgeborene-geschlecht.html

[60] Destatis (2023c).

[61] Ragnitz J. (2023). Modernisierungsschub durch Fachkräftemangel. ifo Institut. URL: https://www.ifo.de/publikationen/2023/aufsatz-zeitschrift/modernisierungsschub-durch-fachkraeftemangel

[62] Moldenhauer J. (2018). Japans Politik der Null-Zuwanderung. IfS. URL: https://renovamen-verlag.de/moldenhauer-japans-politik-der-null-zuwanderung.-vorbild-fuer-deutschland

[63] Deutsche Bundesbank (2021). The slowdown in euro area productivity growth. URL: https://www.bundesbank.de/resource/blob/858448/144b27fb6dae9364eff8c7e6a4a74fb4/mL/2021-01-produktivitaetswachstum-data.pdf

[64] Mann K., Pozzoli D. (2022). Automation and Low-Skill Labor. IZA. URL: https://docs.iza.org/dp15791.pdf

[65] Danzer A. et al. (2020). Does cheap labour supply slow automation innovation? KU Eichstaett-Ingolstadt. URL: https://miwi-institut.de/archives/691

[66] Kofner Y. (2021). Blue Deal: Fiscal and economic effects of the AfD’s economic program. MIWI Institute. URL: https://miwi-institut.de/archives/1284

[67] Acemoglu D., Restrepo (2018) Demographics and Automation. Boston University. URL: https://economics.mit.edu/files/15056

[68] Author’s calculations based on: Destatis (2022). Anteil von Deutschen und Ausländern in verschiedenen Berufsgruppen in Deutschland am 30. Juni 2021. Statista. URL: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/167622/umfrage/auslaenderanteil-in-verschiedenen-berufsgruppen-in-deutschland/ | IAB (2021). Job Futuromat. URL: https://job-futuromat.iab.de/

2 comments